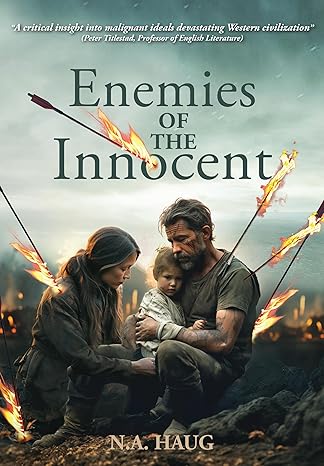

By N. A. Haug.

Academica Press, 2023.

Paperback, 376 pages, $35.

Reviewed by Chuck Chalberg.

This book is at once terribly important and terribly frustrating. How could that possibly be, one justifiably wonders? Put simply and directly, the essential argument is compelling, while the focus could be much clearer.

The author, Nils A. Haug, is a retired trial lawyer and a faculty member of the Intercollegiate Studies Institute. His “particular field of interest” is not particular at all. Rather, it is the “intersection of Western culture with political theory, philosophy, theology, English literature, ethics and law,” each of which is on full and frequent display in these pages.

A learned man, Professor Haug surely is. He is also highly thoughtful, deeply religious (in the traditional sense of that term), and very worried about both the fate of the innocent in particular and the future of the West in general. Without question, he knows the enemy, if only because he likely has had his share of them over the years. He also knows that his enemies are the “enemies of the innocent.” But does he know his audience? Or, more to the point, did he have an idea of who his audience might be when he decided to write this book? The key question is: For whom was this book written, the general reader or the well-informed authority?

A case can be made for both or for no one in particular, and that may well be a good share of the problem. On the one hand, he returns to his main theme again and again, as if he had presumed that he must repeatedly remind the uninformed of what is at stake. On the other hand, the references and allusions presume a great deal of knowledge and interest. In other words, I wonder whether the former will bother to read it and whether the latter will need to read it.

That is too bad, because buried in these pages is an important message that does bear repeating. Whether that repetition should be in different books and via other mediums or in the same book is another matter. The thrust of that message is this: We humans have not just continued to be plagued by the sins of Adam and Eve, but their sins will always plague humanity. In that sense, none of us is truly innocent.

The essence of that sin is our desire to be like God, coupled with our tendency to forget that we are not God. Haug returns to this sin again and again. He also returns again and again to thinkers, ancient, medieval, and modern, who have offered similar reminders. At least he does that when he does not remember to insert brief essays within chapters on modern ideologues, mostly feminists, who have not simply forgotten about God, but who see themselves leading campaigns to crush any notion that God might exist.

Their tone is not Nils Haug’s tone. Their tone is one of anger and arrogance. His is one of worry, even dread. Both, however, are very, very sincere. Haug’s designated enemies are as sincerely convinced that they are right as he is sincerely convinced that they are wrong.

Haug is also a defender of the nuclear family, and they are not. In truth, they seek to destroy the family. In fact, given the additional truth that none of us is innocently sinless, this volume might have been titled “enemies of the family” rather than “enemies of the innocent.”

In the end, and all along the way, it always comes down to the ancient story of secular humanism versus Christian belief. Is there room for yet another book on this theme? Of course there is, and there always will be, so long as fallen man remains fallen.

What heightens interest in such a book at this point in history is the rising power of the left—and the determination of the left to wield power and wield it ruthlessly. Tenderness and compassion are always advertised to be at the heart of leftist policies, not to mention its driving force. But as Flannery O’Connor has reminded us, once tenderness is divorced from Christ, it is “wrapped in theory.” Therefore, once tenderness is detached from the “source of tenderness its logical outcome is terror.” Not surprisingly, that terror can come by way of “forced-labor camps and in the fumes of the gas chamber.”

Since we are now somewhat removed, historically speaking, from the Soviet gulag and Nazi death camps, we somehow presume that we are forever removed from them. Haug presumes otherwise.

Here we are, seventy-plus years removed from Bishop Fulton Sheen’s declaration of the “end of Christendom” and thirty-plus years removed from Francis Fukuyama’s pronouncement about the “end of history,” and the left is increasingly convinced that the future is theirs. Is Haug? In a word, no.

His vision is that of a return to a Christ-centered world. Or, more immediately, at least to a Christ-centered America. To be sure, he would not object to a future dominated by Fukuyama’s vision of some version of liberal democracy triumphing everywhere. But it is the revival and return of Christendom that is primary for him. Only then will secular statism be avoided. For that matter, only then will an Islam that is ascendant and dominant be avoided as well.

Haug’s main concern in this book is not Islam, although he does note its ascendance in Western Europe and rising influence in the United States. Rather, his driving concern is secular humanism/statism, primarily in the United States but also in Western Europe. Haug does not bother to explore the obvious differences between the secular left and Islam, determined as he is to lay bare the sins of the secular left here. And they are legion.

In this single volume, Haug dwells on them all. In single chapters, he covers and repeats multiple themes and issues. For example, chapter six, titled “The Cultural Revolution,” is divided into seven “parts.” Each one of those “parts” breaks down into multiple sub-headings loosely tied to such issues as radical feminism, abortion, homosexuality, transgenderism, critical race theory and practice, and the administrative state, among a few others. And what’s more, they are all there again and again.

So are the usual suspects. Marx, Nietzsche, Freud, Camus, Sartre, Gramsci and others. First in one chapter. Then in another. The same could be said of Haug’s allies, ancients, medieval and modern, whether they be Aquinas, Dostoyevsky, Chesterton, William F. Buckley, or Carl Trueman, among many others, especially Mary Eberstadt, who is always on hand to counter one or another of Haug’s targeted feminists.

Each of Haug’s allies makes frequent and repeat appearances. And all to make the same, repeated point: We are not God. To be sure, today’s enemies are not anything approaching Adam and Eve. They are worse, far worse, armed as they are with both dangerous ideologies and equally dangerous technologies. There is nothing tender—and nothing remote—about the threat they pose.

Haug is very aware of—and very concerned about—this threat. Otherwise, why bother writing this book? But more bother should have been directed at the question of just who it was being written for. The best, not to mention the most important, potential audience might have been a certain subset of general readers and well-schooled authorities.

Who might they be? Homeschoolers and committed Christians? No, they already know what’s at stake and what they must do. The heavily secular left? No, they are the enemy, and they, too, know what’s at stake and what they must do.

That still leaves a great number of potential readers—readers who do not need to be preached to or care if they are condemned but who can and must be persuaded.

Perhaps the moment has arrived to be quite direct. One specific subset of readers must be mentioned: Women. That often means increasingly liberal, even increasingly secular, women. It likely means suburban women. It also means both single and married women. It can mean career women or homemakers. But it has to mean persuadable women. They must be persuaded.

Who knows, Professor Haug might himself be persuaded to take on this very task, especially given his concern, his knowledge, and the timeliness of Flannery O’Connor’s warning. To borrow slightly from Lenin, this is what must be done, and this is what remains to be done.

Will it be written, and will it be persuasive? One can only hope so. After all, to borrow directly from G. K. Chesterton, what is hope, if not hoping when everything seems hopeless?

John C. “Chuck” Chalberg writes from Minnesota.

Support the University Bookman

The Bookman is provided free of charge and without ads to all readers. Would you please consider supporting the work of the Bookman with a gift of $5? Contributions of any amount are needed and appreciated!