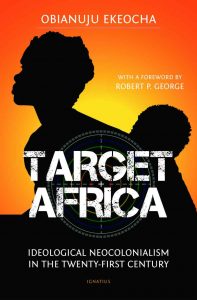

by Obianuju Ekeocha.

Ignatius Press, 2018.

Paperback, 225 pages, $17.

Reviewed by Casey Chalk

In one of the final scenes of the 2006 film Last King of Scotland, infamous Ugandan dictator Idi Amin chastises his reckless and sexually promiscuous Scottish doctor Nicholas Garrigan. Amin declares: “Look at you. Is there one thing you have done that is good? Did you think this was all a game? ‘I will go to Africa and I will play the white man with the natives.’ Is that what you thought? We are not a game, Nicholas. We are real.” That reproof—ironically uttered by one of Africa’s greatest megalomaniacs—still characterizes much of the West’s self-designated role across the continent, a theme made painfully clear in Obianuju Ekeocha’s Target Africa. The Nigerian-born Ekeocha shows how many Westerners, in a spirit reminiscent of their European forefathers, perceive Africa as their personal playground, though now for ideological goals including radical feminism, population control, sexualization of children, and homosexuality. Yet while the author succeeds in presenting a damning tale of Western aggression and manipulation, her appropriation of the same rhetorical tools employed by the Left (“ideological neocolonialism,” “imperialism”) undermines the book’s exposure of Western organizations’ grossly unethical agenda in Africa.

This is a fascinating tale of Western arrogance, intimidation, and exploitation. Despite the powers of our digital age, Ekeocha exposes the misconceptions many Westerners still have about Africa. For example, Africa has a higher proportion of female leadership at the highest levels of state than any other continent, including Europe. This trend is even visible at lower political levels: Rwanda’s parliament is 64 percent female, the highest in the world, and far higher than the United Kingdom (29 percent). These false perceptions are perpetuated by Western media’s excessively negative reporting on the continent. This is in spite of Africa’s many economic success stories—a 2014 survey found that one in three Africans entered the middle class in the preceding decade. Media’s liberal bias (see, for example, CNN’s “African Voices”) also makes it less likely to report on prominent Africans who reject various tenets of the progressive globalist agenda. Nobel Peace Prize recipient Wangari Maathai, for example, has emphatically denounced abortion as “wrong,” and the the “killing [of] unborn children.”

Ekeocha is at her best when exploring the many ways Western institutions are seeking to remake Africa in its own image by pushing such hobby horses of the Left as contraception, abortion, same-sex marriage, youth empowerment through sexuality, and the supposed oppressiveness of the traditional family structure. Yet in many cases, what organizations like WHO, UNESCO, UNICEF, UNAIDS, and UNFPA are selling lacks scientific credibility and endangers the lives and social fabrics of African societies. Moreover, these efforts are further tainted by their propensity to line the coffers of Western businesses and corrupt African politicians, rather than the average African.

One example is contraception. Ekeocha notes that the “pro-contraceptive media blitz” in Africa launched by Western institutions doesn’t discuss “failure rates, adverse side effects, and the increased risks of cancer and heart disease.” Nor, she notes, will Africans be told that “promiscuity itself is the leading cause of sexually transmitted diseases.” She catalogues cases where Western development organizations serve as pill-pushers for contraceptives like Norplant, Yaz, and Yasmin, despite the fact that the first was discontinued in the United States because of its many adverse side effects. The second and third, made by Bayer, have in turn elicited thousands of lawsuits in the United States, with plaintiffs claiming the drugs caused blood clots, heart attacks, strokes, gall bladder injuries, and about a hundred deaths. Studies have also shown that the risk of HIV-1 acquisition doubles with the use of hormonal contraceptives, while the use of Depo Provera (DMPA) for twelve months or longer results in a 2.2-fold increase in risk of breast cancer. The average African consumer of these products will never be told any of this. Meanwhile, given 77 million units of unspecified birth control pills were donated for use in Africa in 2014 alone, pharmaceutical companies see their profits soar.

Despite these strengths, Ekeocha’s argument contains a flaw. Ekeocha consistently argues that the West is pushing an ideological agenda upon Africans that they do not want. She cites data to demonstrate that Africans are strongly opposed to abortion (82 percent of Kenyans, 92 percent of Ghanaians, 77 percent of Tunisians, and so on). Ekeocha further argues that “the experts in the halls of Western power disregard the views and the values of an entire nation in order to push their pro-abortion agenda.” The chapter concludes: “an overwhelming majority of Africans say that abortion is intolerable, whether legal or illegal. It is time for the international community to listen to the voices of the African people and to desist from pushing abortion on them.” Yet this is a problematic argument as it presumes that popular vote should always prevail.

To see the error of this line of argumentation, consider another view commonly held in some African countries: that apostates from Islam should be punished, if not executed. Apostasy laws are on the books across Muslim North Africa, and in some countries, most notably Egypt, a majority of the population supports these laws. In other countries, such as Sudan, Christians are persecuted by local populations and then brutally executed by the state. As Ekeocha suggests regarding abortion, should the international community listen to the voices of those North Africans and not promote religious freedom on the continent?

Elsewhere Ekeocha censures Western organizations that seek to alter long-standing African cultural mores. She cites foreign attempts to persuade her own tribe, the Igbos of Nigeria, that homosexual behavior is acceptable. She writes, “to persuade Africans otherwise, to convince them that marriage and sex are even possible between two women and two men, would require destroying their language and their culture.” As an aside, to claim that African culture writ-large is opposed to homosexuality is a bit problematic: Charles Lwanga and the Ugandan martyrs of the 1880s were executed in part because of their refusal to engage in homosexual acts. What Ekeocha seems to be really arguing is that the fashionable leftism of Western neocolonial elites is merely a reflection of their own prejudices, which is true enough, and that these prejudices are themselves wrong—which may also be true, but is a separate line of argument.

We see this in her defense of tradition. Ekeocha wants Western nations to respect the traditional practices and sentiments of African peoples. But she is mindful that some abhorrent cultural practices, like female genital mutilation (FGM) and child marriage, persist as normative in some African communities. Ekeocha even urges African nations to “unanimously decide to outlaw FGM and child marriage.” Yet this is itself an example of attempting to upend the longstanding cultural norms of an indigenous people. In effect, the basis for her rejection of some practices, and defense of others, rests in Ekeocha’s own normative views, which are opposed to the dangerous and condescending attitudes of Western secular elites.

Ekeocha has rightly placed a spotlight on the egregious immorality of much of postcolonial Western influence in Africa. This, I think, is the primary offense of Western nations and organizations—pushing an unethical, dangerous, and often unscientific sexual and socio-cultural agenda on the African people. Perhaps secondarily is the fact that these same Westerners’ activities on the continent are often paternalistic, sanctimonious, and selfishly profit-seeking. The latter sin is also damnable, but in a manner more akin to the arrogant missionary or greedy businessman—the “product” either man is selling could actually be an objective good, but the tactics utilized undermine one’s credibility and effectiveness. It is the second transgression that might properly be termed “neocolonialism.”

In one especially provocative statement, Ekeocha declares: “The new colonial masters are using donations to recreate Africa in their own image, through the introduction of their ideas about sex, freedom, and human development.” Her use of this oft-used whipping boy of the Left is certainly a creative and provocative appropriation of the rhetoric of her opponents. Yet if the author acknowledges the reality of a natural law or universal truth, as Ekeocha seems to do in reference to sexuality, then such a tactic may be a challenge for her objective. If such universal truths exist, then it wouldn’t necessarily be an objectionable offense for one culture to seek to influence another culture to accept them, perhaps even through imposition, as was often the case with Christianity’s expansion across the Medieval and modern world. Western institutions that manipulate African governments to accept the tenets of the sexual revolution, in Ekeocha’s eyes, are a prime example of neocolonialists. But in other areas, such as religious liberties, such influence may be welcome.

There are indeed many corollaries between nineteenth-century European colonialism and twenty-first-century Western development programs. Just as Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness shed light on the egregious evils perpetrated by the Belgians and their mercenaries in the Congo, so has Ekeocha proved Western institutions’ villainy and corruption across a continent of which most Westerners remain largely ignorant. Yet in elevating the theme of neocolonialism as the primary prism through which to interpret current political and socio-cultural events, the author has unintentionally undermined her own attempt to clarify right and wrong, good and evil. Ultimately, current Western efforts to propagate an ideological revolution in Africa are wrongheaded not because they evince similarities with a previous historical era, but because they are inherently immoral. This is the real injustice perpetrated by Western forces across Africa—a cadre of “scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites,” whom, as Jesus declared, “traverse sea and land to make a single proselyte, and when he becomes a proselyte, you make him twice as much a child of hell as yourselves” (Matthew 23:15).

Casey Chalk is a graduate student in theology at the Notre Dame Graduate School of Theology at Christendom College. He is also an editor of the ecumenical website Called to Communion.