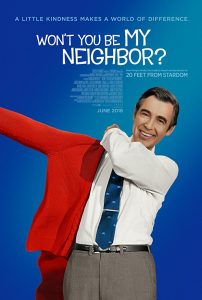

directed by Morgan Neville.

Tremolo Productions, 2018.

Running time: 1 hour, 34 minutes.

By Ryan Shinkel

The neighborhood could have never been that friendly. There must have been scars or tattoos underneath all his sweaters, my fellow grade-schoolers gossiped. Why else would he wear them? His character was like Santa’s beard, a put-on. No way was Mr. Fred Rogers like that in real life. Such millennial suspicion comes from the fact that it feels so rare today to have a saint for a neighbor, especially one on television. Yet in an age of Hollywood scandal and fallen heroes, Rogers’s humility and amity brighten our dark screens.

I did not always think so. Habituated to a show of slapdash and sarcastic buffoonery that made the brilliant Tom and Jerry look tame, my ten-year-old self was at Rogers’s death not attracted to the leisurely pace of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood and too unfocused to notice his theatrical ingenuity and genuine humanity. Ten years later, as a UHB college conservative with curmudgeonly views, my twenty-year-old self assumed that Rogers, along with self-help gurus, New Age mystics, and Barney songs, helped comprise “the culture of narcissism.” That famous line—“You are special just the way you are”—sounded too much like a pill of entitlement. Five years later, walking with three other viewers, all teary-eyed, from a late-night showing of Won’t You Be My Neighbor? (2018), I knew I was amiss. This well-crafted documentary on the life and philosophy of Rogers helps to reveal him as a televangelist in public education for children—one we needed but did not deserve.

Filmmaker Morgan Neville—known for The Best of Enemies, his excellent 2015 documentary about the 1968 televised debates between Gore Vidal and Bill Buckley—shows that your friendly neighborhood Mr. Rogers was the path not taken by television. A Presbyterian minister in public broadcasting, Fred Rogers was not the wolf of Aesop who dresses in sheepskin, but rather the little child of Isaiah who leads the wolf to dwell with the lamb. He really believed that the meek shall inherit the earth, and he preached it on the blue tube.

Born in 1928, Fred McFeely Rogers came into a privileged family and grew up as a portly child. “Fat Fred,” as they used to call him, had to exercise his imagination by himself. He developed not just sympathy but empathy for the lonely drama of childhood. We all experience it. He never forgot it. A lifelong Republican, Rogers was political in that postwar way of treating all Americans as created equal. A lifelong Christian, his religion was devout and inclusive to the received wisdom of other traditions. He entered seminary, only to leave it for public television, then entered it again, only to finish and return to public broadcasting. In his first informational encounter with children, he would later relate, they had a test. One boy named Thatcher told the classroom how the ears came off of his pet giraffe. As Rogers replied how the ears and noses and arms and legs of our toys fall off, but that our features and limbs do not, the boy’s eyes grew wider and wider. Rogers passed his test to enter the kingdom of childhood.

Chesterton suggests the plainest difference between fable and fairytale is that there cannot be a good fable with humans in it, and no good fairytale can be without them. Rogers bridged the gap by writing, directing, and filming, but never appearing in the Neighborhood of Make-Believe. He appeared only in his fictional home. King Friday XIII and Daniel Tiger, his alter egos, stayed on the other side of the trolley ride. Lady Aberlin and Mr. McFeely might appear, but Rogers never entered any of his puppet stories. His slow-paced sweater vesting, feeding of fish, and breathing exercises were low tech, but like all good stories, were actually about something. He drew from his experience and the best contemporary child developmental psychology to talk to kids on their own terms. His “placidity belied the intense care he took in shaping each episode of his program,” notes Maxwell King. “He insisted that every word, whether spoken by a person or a puppet, be scrutinized closely, because he knew that children,” especially the preschool boys and girls of his core audience, “tend to hear things literally.” While he regretted what all too often became the tomfoolery screened directly to young brains, he sought balance between imaginative entertainment and sentimental education.

Rogers always spoke to audiences, young or old, while focused as if speaking to one single person, and usually while telling a story to evoke emotions proper to neighborliness. The documentary features the 1969 Congressional testimony on funding public television that made Rogers nationally famous. To save the $20 million annual budget of PBS, he spoke extemporaneously and directly to Senator John Pastore about his fifteen year work. Assuring the Senator that he was “very much concerned, as I know you are,” about violent animation delivered to American children, he had “worked in the field of child development” and was “trying to understand the inner needs of children.” His shows dealt with “the inner drama of childhood,” so “We don’t have to bop somebody over the head” to get “drama on the screen” but can “deal with such things as getting a haircut, or the feelings about brothers and sisters, and the kind of anger that arises in simple family situations. And we speak to it constructively.”

Prompted by the senator, Rogers explained his program, noting how “I give an expression of care every day to each child, to help him realize that he is unique” and to show through public television how “feelings are mentionable and manageable.” It is “much more dramatic that two men could be working out their feelings of anger” rather “than showing something of gunfire.” After Rogers explained his work before and behind the camera, Pastore admitted, “I’m supposed to be a pretty tough guy” but “this is the first time I’ve had goose bumps in the last two days.” Rogers then gave a simple song that teaches listening children how to have self-control despite being angry. In less than six minutes, the Senator switched positions, becoming tearful. “I think it’s wonderful. Looks like you just earned the 20 million dollars.” In the song one hears not emotivism but a true counterculture, both to baby boomer rebellion and postwar consumerism. His televangelism was made for late night satire yet was a road not taken—what David Brooks calls “the loveliness of the little good.”

Rogers was more than meets the eye. He spent whole weeks on subjects from death to how small kindly acts do great things. His timely shows gave subtlety, where preaching was invitation, whether, as when RFK was killed, in explaining what assassination is, or in showing the absurdity of segregated pools by having Rogers and Officer Clemens put their feet in the same kiddie pool. But Rogers was not your usual “tamed” lion. A vegetarian tolerant of gay people, he showed disabled kids how to normalize their existence and had kids breakdance as well. One series he attempted for adults, ambitious yet unsuccessful, featured subjects from beauty to music, including interviewing his friend, the cellist Yo-Yo Ma.

His spritely humor disarmed his parodies, even SNL’s Eddie Murphy playing yokel Mr. Robinson. Ali Trachta mentions a story. “One day when Fred was at Rockefeller Center for meetings, he ventured down to the SNL floor to knock on the comedian’s door. ‘It’s the real Mister Rogers!’ he apparently said, grinning at a visibly embarrassed Murphy.”

Walking from away from the film, I kept thinking of two quotes Rogers gave. First, that the job of adults is to protect the world of children from other adults who would encroach onto that world to form them. Second, that our duty—he quoted from an Arabic phrase in his 9/11 anniversary special—is to restore creation. His approach to public television came from a theological vision that acknowledged the divine image within every human being.

Rogers began at a time when, as Frank Capra complained, “the daring villainy of the non-hero of the fifties was but a pale imitation to the savagery of the anti-hero of the sixties,” when stars took over filmmaking from formerly dictatorial studios. Then came the seventies’ creative destruction that produced a plethora of classic films and generational directors—from Coppola, Spielberg, and Lucas, to Scorsese, Polanski, and Allen. Every production was “a kind of freelance job” that everyone “signed up for,” which made great art and “coincided,” as John Podhoretz notes, with a “general period of American liberation” from conservative mores for looser rules over language, sex, and violence. The same is occurring in our golden age of television, from The Wire to Breaking Bad, as online platforms—Netflix and Amazon—enable similar conditions of freer productions that deconstructed 1970s archetypes in more experimental and vulgar plots, while films now fall among bland actions or comedies, superhero films, and arthouse Oscar contenders. As film declines, television productions often give deeper themes.

The mass-culture gatekeepers of yesteryear were superficially conservative and nice to religion from fear of offending any potential market. Midcentury theologians actually critiqued culture for its mediocre debasement, but religious conservatives became silent on that note as the sixties and seventies counterculture marched through the institutions. Ironically, as Ross Douthat argues, the loss of disincentives against controversy enable, along with mediocre smut, the “raw materials of blasphemy” as well as “the stuff of popular art that drills deep into issues—theology and human destiny, sin and redemption, heaven and hell—that the old mass media treated with kid gloves.”

Yet theological and moral provocations still come with a converse anthropological vulgarity. Exemplifying the golden age shows, The Sopranos fused sex and violence with Shakespearean power struggle and relatable family drama to inaugurate the televised age of the antihero, with upticks in sex and violence accompanied by intricate storytelling and ambitious production value. Sonny Bunch notes that other shows followed suit in which anything goes morally. But this golden age has supports of lesser metals. That these shows intimate diverse ideas is debatable. Global reception to American media is potentially dangerous, and the loss of actual heroes is perhaps even psychopathological. The provocative golden ages of theater houses and home screens have a dark side of vulgarity and scandal, from looser mores preached on screen to sexual predation in the industry. “I came of age in the ’60s and ’70s,” said Harvey Weinstein; “that was the culture then.” Contrasts to that time are noteworthy. Rogers was a critic of that culture then, and perhaps therefore still remains a notable, and even noble, contrast to ours now.

Mr. Fred Rogers was a neighborhood role model. What was his secret to appeal to so many, child and adult? Read Anthony Breznican recount the personal generosity of Rogers spontaneously acting as a grandfather to him when his own grandfather had died, and it becomes clear the man was, in the fullest sense, holy. His persona in popular culture is worth considering, for his style persisted as the country chose another path, more exploratory theatrically yet poorer of ethos, that has resulted in our culture wars and tribal politics. His education show was deliberately paced in contrast to cartoonish frenzy and still models a sharp distinction to our digital age. “Have smartphones destroyed a generation?” Jean Twenge asks, documenting how adolescents are more comfortable online than offline, physically safer but lonelier, and more depressed than perhaps any human generation before. As these developments in entertainment and technology arose, the religious right failed in defense of yesteryear’s doomed mass culture, while a class separation grew underneath the managerial elite. Against this cultural decadence, one minister took a less traveled path. What he preached resonated with my three compatriots for good reason. This documentary shows how nuance of thought, deliberate imagination, and generosity of spirit was once something desirable. And Mr. Rogers shows a more genuine and generous way to take back the neighborhood.

Ryan Shinkel is a historical researcher for American Bible Society and a graduate student at St. John’s College in Annapolis, Maryland.