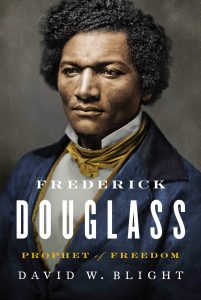

by David W. Blight.

Simon and Schuster, 2018.

Hardcover, 888 pages, $37.50.

Reviewed by Annelisa J. Purdie

Frederick Douglass (1818–1895) is a remarkable and compelling figure in American history. His portraits are among the most recognizable images of nineteenth-century Black American figures, having been widely reproduced across a variety of mediums. From its initial publication in 1845, his Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass has entered the public consciousness as the seminal slave narrative, capturing all of the elements of the genre and becoming an American classic. Scores of scholars and public figures (both contemporaries and those impacted by him long after his death) have used the orator’s fame for their own ends, shaping his legacy into an image that best fit their own ideals. (After all, he’s “getting recognized more and more,” and “has done an amazing job” at, well, being Frederick Douglass, one supposes.) In Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom, historian David W. Blight attempts to provide a complete picture of his subject, showing the complexities of the man and the world he inhabited. The result of this self-described labor of love is more than worth the read. Blight has long been praised for his ability to make even the most mundane of details seem appealing to the average reader, and he uses his congenial writing style to provide details about Douglass’s life that may be unfamiliar to even the most intensely focused of Douglass scholars.

Douglass was and is many things to many people: orator, statesman, acerbic author, provocateur of America’s deepest hypocrisies, hopeful citizen. It is telling that Blight positions Douglass as “prophet.” Douglass often warned of the impending breakdown of American society were Black Americans not permitted to exercise the full scope of their rights, as well as the negative effects certain to arise from willful obliviousness towards America’s original sin. Neither was he afraid to denounce the mendacity within American culture that nurtured this sin in the first place, which was especially prevalent in the realms of religion. “I can see no reason,” he asserted, “but the most deceitful one, for calling the religion of this land Christianity. I look upon it as the climax of all misnomers, the boldest of all frauds, and the grossest of all libels.”

The text succeeds in its emphasis on Douglass’s most powerful and frequently used tool: his voice. Throughout, Blight demonstrates the manner in which Douglass used this instrument to make his story known across his travels, never bowing, never conceding, but modulating his tone and intention to fit different circumstances. Blight asserts that the usage of Douglass’s voice, both literal and figurative, served as a necessary rebuke to prevailing notions about the intelligence and capabilities of Black Americans. In his mastery of the very thing that it was believed he had no right to possess, Douglass was able not only to plead his cause but to create his own identity—which served as a means of pride and protection against the outside world and helped make himself into “an edifice so strong that no surge of racism, no embittered rivalry, no lynch mob, no conservative Supreme Court decision, no Lost Cause romance, nor even the ravages of time could tear down.”

The author demonstrates how Douglass both shaped and was shaped by his environment, gleaning from the culture around him while attempting to carve out his own place in a world that frequently rejected the very notion of his humanity. Blight does not shy away from the contradictions and complexities of Douglass’s life, showing indeed how Douglass often became the biggest impediment to understanding himself by constantly reinventing his story and leaving out crucial elements that would help to provide a more complete picture. (Whether this was a subconscious self-protective measure on Douglass’s part remains to be seen. It will likely serve as a source of debate among scholars for years following the distribution of this text.)

Here is Douglass’s complete intolerance for the institution and aftermath of slavery, coupled with his steadfast belief in America’s potential to live up to the best of its ideals. Here is the nagging suspicion that he may have been fighting an increasingly losing battle, coupled with his dogged desire to keep pushing toward a positive horizon that he may have been unable to visualize. And here is the anguish of that child who never experienced the most basic of human relationships and often withheld from his own children the same gentleness and understanding that he longed for. Blight depicts these contradictions in full honesty, without judgment or baseless speculation. He does an excellent job in acknowledging Douglass’s foibles and complicity in muddying his own story while refusing to condemn him outright.

Each of Douglass’s three autobiographies, for example, differs radically from the others, displaying discrepancies in content, tone, and recollection of historical events. In contrasting The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (1881) with My Bondage and My Freedom (1855), Blight demonstrates how Douglass sought to adjust his narrative to fit the conventions of the age—the Gilded Age, to be exact. “This age of Progress required a writer with Douglass’s story to be a kind of missionary for success, and therefore to distance himself from his roots and from the Southern black folk around whom he found a beginning.” It is left to the reader to decide how these often baffling contradictions should shape one’s view of Douglass and his legacy. Douglass’s methods for navigating oppressive and difficult social spaces may disappoint some readers, but Blight helps to hold the intention behind Douglass’s decisions open for debate.

One of the text’s most fascinating elements is its focus on the complexity of Douglass’s family life. This reviewer has always been fascinated by the enigma of Anna Murray-Douglass, the orator’s first wife and, in many ways, the first and strongest supporter on his road to notoriety. So little of Murray-Douglass is left in her own words, however, that it becomes difficult to analyze her character and uncover her feelings from her own perspective, free of interlopers. (This conundrum is exacerbated by Douglass’s strange reticence to give mention of the importance of his wife’s role in his life, yet another cipher likely to provoke scholarly discussion.) Blight attempts to shine more light on this intelligent, strong, and demure figure and show her own set of complexities. We begin to see her contributions as more than that of an over-idealized, near-invisible vapor in the background, but are still left wanting more.

Blight also does not retreat from Douglass’s sometimes tender, often tempestuous relationship with his extended family, in particular his children and his in-laws. The filial and conjugal bonds within the Douglass household deserve their own volume with its own extensive set of notes. Blight’s meticulous presentation of the communiqués between the Douglass paterfamilias and his offspring, as well as his well-informed insight, often reads like a comedy of manners, both scholarly and appealing to the reader. As with the life of Douglass and his wife, there is much here to parse and more yet to be uncovered; one can only hope that another enterprising historian will undertake the task in the future.

What Chernow has done for Alexander Hamilton, what Rampersad has done for Langston Hughes, what Giddings has done for Ida B. Wells, Blight has done for Frederick Douglass. This book is a welcome addition to any library for period scholars and amateur historians, and for anyone who wishes to simply learn more about this icon of American history. To slightly paraphrase the inimitable Dorothy Parker: This, dear readers, is not a book. It is an experience. And it is more than worth the investment. With anticipation, and with gratefulness for its existence, onward we go.

Annelisa J. Purdie holds a Master of Arts in American Studies from Columbia University, as well as an Master of Library Science from St. John’s University. She currently works as a librarian.