By Tucker Carlson.

Free Press, 2018.

Hardcover, 256 pages, $28.

Reviewed by Sumantra Maitra

Boris Johnson, before he turned to a goofy Mayor of London and subsequently the architect of Brexit, was a journalist and scholar known for his book on Sir Winston Churchill. Johnson wrote that one of the reasons behind Churchill’s popularity was his instinctive grasp of Greek rhetorical tropes and his use of sudden short punchlines to conclude an otherwise orotund argument with Latinate words. Put another way, Churchill was a remarkably talented speaker, but his oratorical mastery was in simplifying complex circumlocutions to powerful short sentences that reach common people.

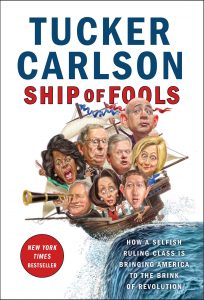

Speaking of short, powerful sentences, Tucker Carlson’s new book, “Ship of Fools: How a Selfish Ruling Class Is Bringing America to the Brink of Revolution” is a one-two punch in the snoot of our craven heedless intelligentsia. At the time of writing, Carlson’s show is rising in popularity, despite attempts by liberal activists to instigate boycotts on trumped up (pardon me) charges. For those who watch the show, the reminder of short, sharp sentences will seem familiar. For example, talking of Trump’s election, Carlson writes, “it was a gesture of contempt, a howl of rage, the end result of decades of selfish and unwise decisions made by selfish and unwise leaders. Happy countries don’t elect Donald Trump president. Desperate ones do.” The tone is set. You instantly recognize what you’re here for: a splash of cold water to your face after a misplaced mid-afternoon siesta and subsequent headache. Liberal utopia of the last quarter century is over with failed foreign humanitarian interventions and domestic social disintegration; now back to reality.

Carlson’s book is distinctly bipartisan in the sense that it mercilessly skewers conventional wisdom, takes no prisoners, and shows no reverence for any tribal party loyalty. The enemy is the imperial intelligentsia, deciding on the course of the country from their upmarket properties, practically indistinguishable between a Bill Clinton and a Bill Kristol. “Our new ruling class doesn’t care, not simply about American citizens, but about the future of the country itself. They view America the way a private equity firm sizes up an aging industrial conglomerate: as something outdated they can profit from. When it fails, they’re gone,” Carlson writes. From immigration to foreign intervention, democracy has no meaning anymore because the ruling class, regardless of political party, chose to consistently ignore what the demos want. If the demos raise their voices? Well … import new demos. Carlson thunders against ersatz democracy, dubbing it a recipe for revolution. “If you tell people they’re in charge, but then act as if they’re not, you’ll infuriate them. It’s too dishonest. They’ll go crazy. Oligarchies posing as democracies will always be overthrown in the end.”

The strongest section of the book is the one dealing with foreign interventions, especially the characters who led the West to recent foreign entanglements. Carlson points to a culture of mediocrity, an insulated blob, so to speak, who never go to war themselves, nor face any direct consequences for their boneheaded policies of destabilizing faraway semi-feudal lands where the United States or the West have no direct geostrategic interest. Imagine the pith helmet and khaki-wearing stoic British imperial civil servant in London arguing for organizing the logistics for a British Australian and Indian army expedition in North West Frontier Province to quell Afghan rebels. Fast forward two hundred years, and change Australia to Arizona or Alabama. What are the odds that Max Boot, sitting in DC, is also a fan of imperialism?

One thing that every late-stage ruling class has in common is a high tolerance for mediocrity. Standards decline, the edges fray, but nobody in charge seems to notice. They’re happy in their sinecures and getting richer. In a culture like this, there’s no penalty for being wrong. The talentless prosper …

So Carlson opens fire on the foreign policy establishment, which has nothing to show for success in the last fifteen years and yet gets regular columns in the top-tier newspapers and gigs in think tanks and self-referential journals to shape public opinion. “A generation ago, it would have been hard to imagine a newspaper like the Washington Post celebrating Max Boot.” Well yes, but for the Washington Post, the war of choice is now domestic regime change in Washington DC, and Max Boot is ideally suited for advocating it.

This mindless internationalist utopianism was bipartisan, and in some cases far more so on the liberal than on the conservative side. Among the right were always libertarians wary of war expenditure, paleoconservatives who trend isolationist, and some fiscal conservatives, who saw open-ended engagements as foolish. Liberals (and their neoconservative cousins) on the other hand—ideologues that they are like the Trotskyites before them—wanted to shape the globe in their image. “In the fall of 2002, a total of seventy-seven senators voted in favor of the Iraq War resolution. This included the majority of Democrats, and 100 percent of the party’s rising stars. Two future presidential candidates who voted for the war, John Kerry and Hillary Clinton, also happened to be future secretaries of state. The future vice president, Joe Biden, voted for it …”—a piece of trivia often overlooked these days.

The scenario repeated in Libya. “In 2011, Hillary Clinton and other interventionists in the administration convinced Obama to support the overthrow of Muammar Gaddafi in Libya.” The predictable result followed. “If there’s a single lesson of the Iraq War, it’s that chaos is worse than dictatorship. Libya looked like a prime candidate for chaos. With Gaddafi gone, it was obvious that the place might devolve into a lawless mess and become a bug light for extremist groups. Hillary Clinton and Samantha Power of the National Security Council didn’t agree. They viewed Gaddafi as a deeply immoral man. That’s all the justification they needed to take him out. So they did.” The rest is what we see. From human trafficking to mass migration to terror hub and slave trading, the entire North African coastline is now little different from hell after the collapse of authority. And that is where Trump was different.

Carlson cites the first time, on February 13, 2016 in South Carolina, that Trump charted his different path, different not only from his fellow Republicans but also from all the Democrats:

Trump articulated something that no party leader had ever said out loud. “We should never have been in Iraq,” Trump announced, his voice rising. “We have destabilized the Middle East.” Many in the crowd booed, but Trump kept going: “They lied. They said there were weapons of mass destruction. There were none. And they knew there were none.” Pandemonium seemed to erupt in the hall, and on television. Shocked political analysts declared that the Trump presidential effort had just euthanized itself.

But it didn’t. Voters liked it, even when Max Boot and Bill Kristol didn’t. And the seeds of resistance against any Trump administration was also born. “Napoleon Bonaparte seized control of France, crowned himself emperor, defeated four European coalitions against him, invaded Russia, lost, was defeated and exiled, returned, and was defeated and exiled a second time, all in less time than the United States has spent trying to turn Afghanistan into a stable country.” Trump understands this. The American people understand this. A handful of foreign policy conservative realists understand this and are in turn regarded as populists by the bipartisan internationalist blob.

The ending of the book is a bit abrupt. While it is not admittedly Carlson’s job to suggest alternative policy suggestions, Trump has been in power for over three years now. What effort has been made by the Republicans in this time to form an alternative intellectual body or group of scholars, communicators, media men, academics, economists, and foreign policy think tankers to promote coherent conservative realism? After three years, that goal remains somewhat inchoate, though such journals as Modern Age, American Affairs, and First Things have all made efforts in that direction.

But where’s the post-Trump line of GOP candidates? If conservative realism is what Americans crave, and if this line of ideas has currency, then it should not be a problem to find5 policymakers to articulate it. Rage, while important in times of crisis, ultimately needs to be channeled and given a coherent direction. Carlson’s book does an excellent job in explaining the causality of what led to this bipartisan failure of the last twenty-five years. Perhaps policymakers should take note.

Sumantra Maitra is a doctoral researcher at the University of Nottingham, UK, and a writer for Quillette Magazine, The Federalist, NRO, and Claremont Review of Books. You can reach him on Twitter @MrMaitra.