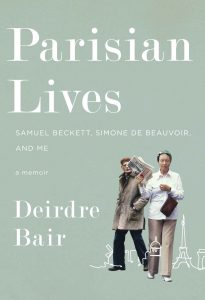

by Deidre Bair.

Nan A. Talese, 2019.

Hardcover, 368 pages, $29.95.

Reviewed by Michial Farmer

When she set out to write her award-winning biography of Samuel Beckett, Deirdre Bair had never even read a modern biography. Nevertheless, she was particularly qualified to write Beckett’s, having worked as a journalist for a decade, having just written a dissertation on his fiction, and—perhaps most importantly—having the courage or gall to write him a letter offering to do it. Even then, he didn’t make it easy, from the very beginning: Beckett unexpectedly left Paris for Tunisia just as Bair arrived, leaving her to navigate a labyrinth of delays and silences without any direction from him. Nearly half a century later, her latest book, Parisian Lives, tells the story of her writing Samuel Beckett: A Biography and its follow-up, a biography of Simone de Beauvoir.

At Columbia in the late 1960s, she found herself a triple outsider: a woman in an overwhelmingly male space; a woman committed to her family at the expense of the political ideals of the time; and a somewhat old-fashioned reader who found the vogue poststructuralism of that era “convincing in the main but still unholy” and who was interested in uncovering something as déclassé as Beckett’s intentions. She persevered in her approach largely because she’d never totally swallowed the career goals academia set on her plate, and Parisian Lives tells the story of her procuring, almost by accident, a professorship at the University of Pennsylvania—though her colleagues at that school made it very difficult for her to progress.

Bair reveals that her book on Beckett was essentially a biographie à thèse, meant to prove, like her dissertation, “that Samuel Beckett was not (as the reigning view in the academic community then held) a writer steeped in alienation, isolation, and despair, but rather one who was deeply rooted in his Irish heritage and who portrayed that world through his upper-class Anglo-Irish background and sensibility.” And yet readers of Samuel Beckett: A Biography know that her tone is studiously objective, not tendentious. Parisian Lives reveals the motivations behind this approach: Bair was determined to approach her biography as a consummate professional, in part because she had the sense early on that Beckett approved her project only because he didn’t take her seriously. So she strove for professionalism and total objectivity, refusing to become involved in Beckett’s life and rebutting propositions from men in his circle. This technique began as self-preservation but became her reigning principle as a biographer. Parisian Lives thus inhabits a totally different world from her previous books, even though it shares their cast of characters: In those books, she refuses to use a first-person pronoun outside of their introductions; here, she will reveal the autobiography underneath the biography.

Readers looking for literary gossip will certainly find some, especially now that the major parties are dead and buried: Bair’s story of her week spent interviewing the aged bohemian socialite Peggy Guggenheim at her Venetian estate is especially scathing, climaxing with a vicious bon mot from Lillian Hellman. But even here one gets the sense that Bair has no scores to settle; relating the story of one of Beckett’s friends who enthusiastically helped her and praised her book, only to claim decades later never to have spoken to her, Bair is quizzical, even philosophical, rather than hurt or angry. Even her personal matters are more or less objective. That tone changes over the course of the book, however. Early on, her technique is to treat her younger self as a biographical subject and to approach herself as an objective outsider. She is helped in this task by what she calls her Daily Diaries, or DD, extensive working notes for her earlier books:

My DD permitted me to present myself as I was then, the young woman writer feeling her way toward a new kind of writing, even as the self who writes this now is using the perspective of time and distance. The older (and I hope wiser) me needed help to recall that brash young woman who became aware only gradually that she was upending a small slice of cultural history in a time of significant social change.

The diaries themselves, from which Bair occasionally quotes, are substantially more subjective than the early chapters of Parisian Lives. They are, in effect, the unreliable interviewee whose words Bair must get behind to find the real truth of the matter.

But as the book progresses, she becomes more and more emotionally involved with the story she’s telling, as if we were talking to her at a cocktail party and she needed a few drinks to loosen up. By the book’s midpoint, she is perfectly willing to tell us about the boorish behavior of John Montague, an Irish friend of Beckett’s who invited himself and his family to live with the Bairs for six weeks. And she’s certainly willing to talk about her mistreatment at the hands of the overwhelmingly male Academy and especially the academic Beckett cult—or, as she amusingly calls them, the Becketeers.

In fact, she seems to have been pushed toward a feminist awakening by the Becketeers’ repeated insistence that she collected the material for her biography by sleeping with Beckett and with whomever else she needed to. (She emphatically did not.) She wrote her second book, the biography of Simone de Beauvoir, because at the time she saw Beauvoir as having threaded the modern woman’s impossible needle: In her public presentation, at least, she “had a solid professional life, one that garnered respect and admiration,” but also “a happy and satisfying personal life.” Whereas she began writing about Beckett almost at random, writing the name of every writer in whom she was interested on notecards and absentmindedly alphabetizing them, her choice of Beauvoir was quite personal, even aspirational.

With that in mind, it’s no surprise that she became almost friends with Beauvoir—and also that she learned that Beauvoir’s life was not as exemplary as she imagined. Simone de Beauvoir: A Biography was one of the first critical sources to reveal that Beauvoir’s relationship with Sartre was not as idyllic or as egalitarian as the two of them claimed. Bair’s attitude toward Sartre in the Beauvoir biography is conflicted: He is somewhat callous toward her emotions, but he also helps her to flourish as a thinker and an unconventional woman. In Parisian Lives, on the other hand, Bair’s disgust is apparent; she scarcely mentions Sartre without noting that he was short and ugly, with body odor and halitosis, and that his sexual insatiability caused real harm to Beauvoir, even if she was largely unwilling to admit it herself. Her struggle in writing about Beauvoir, she reveals, was to make it her story, not Sartre’s, who was such a dominating force in her life that Beauvoir claimed up to the end that her work was essentially a footnote to his. Both Simone de Beauvoir and Parisian Lives make a case for Beauvoir’s being fascinating in her own right, parallel to Sartre but by no means dependent on him.

Fans of the two principals in Parisian Lives will no doubt find the book entertaining and interesting, even though it’s hardly an essential addition to our understanding of Beckett and Beauvoir, as the biographies are. But it gives us a fascinating view of the intellectual environment of the 1970s and 1980s, and of how very difficult it is to write a biography. And Bair herself emerges as an engrossing character, a woman attempting to live in two or three worlds at once while blotting herself out of her public work altogether. All these years later, it’s nice to see her poke her head around the corner.

Michial Farmer is one-third of the Christian Humanist Podcast and the author of Imagination and Idealism in John Updike’s Fiction (Camden House, 2017). He lives in Atlanta.