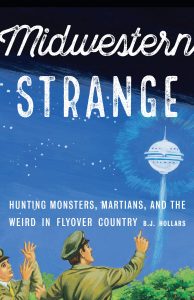

by B. J. Hollars.

University of Nebraska Press, 2019.

Paperback, 208 pages, $20.

Reviewed by Jacob A. Bruggeman

It was around the time of my ninth birthday that I realized the Loch Ness Monster did not live in the reservoir at Hinkley Reservation, a small body of water near my home in Northeast Ohio. My family, especially my uncles, always assured my brother Ben and me that this submarine monster made a home out of Hinkley Lake. Always lurking beneath the surface, the monster’s emergence was a rare sight. After all, I thought, being a societal outcast meant that the thalassic monster had always to keep its lengthy, lizard-like body submerged; its sunken home, eternally endangered, could never be revealed. In this spirit I spent many hours searching for any sign of a curved, scaly head cresting above the waterline.

The myth of the Loch Ness Monster, or Nessie, is not native to Northeast Ohio, but was transported across the world from the Scottish Highlands after its popularization in the 1930s.

Popular as it is, the legend of Loch Ness Monster is merely one of many bête noire to inhabit America’s material and imagined landscapes. Bogeymen and hobgoblins abound in American myths, many of which, as University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire Associate Professor of English B. J. Hollars discovered in his “year of living strangely,” reside in the American Midwest. Hollars’s new book, Midwestern Strange: Hunting Monsters, Martians, and the Weird in Flyover Country, is the product of that year.

Hollars’s academic career lends credence to his hope that Midwestern Strange might fill a void left by academia’s pitifully small “patience for the weird.” Instead of intellectualizing the Midwestern monsters and myths collected in his manuscript, Hollars states that “this book isn’t about answers. It’s about learning to live in the questions—even when doing so offers a less-than-hospitable terrain.” As Hollars explains in the introduction,

By confronting monsters, Martians, and every strange thing in between, we challenge ourselves to look beyond our preconceived notions, to parse fact from fiction in an effort to come to our own thoughtful conclusions. My hope is that by lurching around in the muck for a while we might emerge—not with answers—but with a sharpened skill set to assist us in our shared search for truth.

If lacking in answers, Midwestern Strange is bursting with stimulating regional and local histories that are simultaneously hair-raising and hilarious. Furthermore, Hollars’s insistence that the strange should not be eliminated but seriously engaged with works to encourage in his readers an acceptance of mystery. John Keats’s concept of “negative capability” and Austrian poet Rainer Maria Rilke’s call to “live the questions” are both at home in Hollars’s new book. With this overview in mind, Hollars’s invitation to “wallow in the weird together” is all the more worth accepting.

Hollars’s harrowing tales of Midwestern odds and ends are arranged and presented as “case files” detailing the who, what, when, where, some possible whys, and witness testimonies. Nine in total, there are three case files for each of the subjects listed in the book’s subtitle: monsters, Martians, and the weird. The monsters profiled range from Southeastern Wisconsin’s “Beast of Bray Road,” a werewolf-like upright canine first sighted in the 1930s, to “Oscar the Turtle” or the “Beast of Busco” in Fulk Lake near Churubusco, Indiana, for which the town launched a full-fledged hunt in March 1949.

The most memorable of monsters to make an appearance in Midwestern Strange, however, is the “red-eyed, gray-bodied” ghoulish humanoid, supposedly possessed of “prophetic powers,” known to haunt Point Pleasant, West Virginia: the Mothman. As witness Steve Mallette remembers from his sighting of the monster on November 16, 1966, “It was like a man with wings. It wasn’t like anything you’d see on TV or in a monster movie.” Near midnight on November 15 of the same year, Steve and Mary Mallette were driving with Roger and Linda Scarberry to an old, deserted munitions plant outside of Point Pleasant. When the couples drove up close to the plant, they first noticed a pair of radiant red eyes caught in the car’s headlights. Mmoments later they saw the body to which those eyes belonged: a shadow-like, seven-foot tall body with ten-foot wings sprawling on its back. The couples quickly sped off to Point Pleasant. And though they claim that the Mothman followed them back a short way along Route 62, the airborne anthropoid gave them no trouble.

Following the encounter, Point Pleasant’s community had to try and make sense of the “man-sized, bird-like” creature’s sighting and did so by making it part of the town’s history. Three decades later, The Mothman Prophecies hit the silver screen and popularized the probable myth for many younger viewers. In 2005, Jeff Wamsley of Point Pleasant opened the Mothman Museum. Through claiming the creature as a defining element of the community, Hollars writes, the Mothman has become a “perfect entry point to educate people on Point Pleasant’s rich history.” Understood as such, this Midwestern tale is not simply that of a monster stalking two married couples, but an example of how the Flyover States’ community histories are far more complex than the timeworn sagas of Main Street and amber waves of grain conveyed by stereotypes about region’s past. Lest readers think this reviewer is reading Midwestern pride into otherwise anodyne anecdotes, Hollars claims as much about his stories: “We Middle Americans have grown accustomed to being overlooked, which is precisely why outsiders ought to look a bit closer.”

The Midwestern encounters of the extraterrestrial kind described in Hollars’s volume are of the same abnormality as the Beast of Bray Road and the Mothman. Varying from a mysterious flying object passing over a U.S. Air Force base in Minot, Minnesota in October of 1968, to an abnormal light entering the squad car of Marshall County, Minnesota Deputy Sheriff Val Johnson in 1979, causing what could only be described as “an accident with an unknown object,” these stories do not disappoint.

Case file #4, the first of the three “Martian” tales, describes Wisconsinite Joe Simonton’s “space pancakes.” The story goes like this: On April 18, 1961 a plumber residing in Eagle River, Wisconsin named Joe Simonton (“an unlikely candidate to serve as ambassador for Earth,” jokes Hollars) was visited by a flying saucer just as he finished breakfast. The spacecraft, which Joe described as “two large soup bowls put together,” was floating a few feet above ground when three short aliens resembling “Italians” exited and asked Joe for water. When Joe attempted to start a conversation with these interstellar visitors, one of them supposedly handed him four pancakes. After investigation from a Northwestern University astrophysicist Dr. J. Allen Hynek, who headed the Air Force’s investigations of UFO sightings through Project Blue Book, it was determined that Joe’s encounter was, as Hollars describes it, more likely “a close encounter of the hallucinatory kind.”

But Hollars carefully instructs his readers that Joe Simonton’s story should not be written off as that of some simpleton imagining Italianesque aliens using his back yard as a parking lot. Drawing on critic Susan Sontag’s 1965 essay, “The Imagination of Disaster,” and Swiss psychologist C. G. Jung’s short book, Flying Saucers, Hollars reasons that Simonton’s story might be understood as a product of 1960s popular culture and international politics. In light of the post-WWII images of utter destruction at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the prevalence of science fiction on the page and silver screen, and the threat of nuclear doomsday always dangling from the Cold War’s tenuous peace, Simonton’s story—if we take it to be false—can be seen as a Midwesterner’s projections of popular culture’s tropes and what Jung called “collective distress” onto his everyday life. Interpreting Simonton’s experience and others like it against the psychological trauma of the Cold War demonstrates how the Midwest is inevitably intertwined in national and global phenomenon.

True, Simonton could simply be crazy, but we can never be entirely sure if his story is a verity, deceit, or delusion. For Hollars, this recognition of uncertainty is a necessary lesson in epistemic humility; “there’s no singular key for every lock that needs unlocking,” he writes, just as there’s no single explanation for the Midwestern strangeness upon which his book is staked.

Although the Midwestern monsters and Martians in Hollars’s book exhibit histories and traditions unique to states like Wisconsin and West Virginia, the weird tales in the last three of Midwestern Strange’s case files capture some of the region’s most interesting recorded mysteries. Of Hollars’s final three case files, his report on “the Hodag” of Rhineland, Wisconsin in case file #7 stands out as exceptionally Midwestern. The Hodag’s story dates back to 1893, when Wisconsinite Gene Shepard’s walk through the woods brought him upon a black monster resembling “a cross between a lizard and an ox,” equipped with “razor-sharp fangs and horns” and nostrils emitting “fire and smoke.” Shepard returned to town and rallied Rhineland’s hunters to search for and slay the beast. When the hunters returned to the spot of Shepard’s original sighting, the Hodag emerged and eviscerated the party’s dogs. “Desperate,” Hollars writes, “they turned to their dynamite sticks, hurling them at the creature, who absorbed the blasts until catching fire and smoldering to death—but only after nine horrific hours of thrashing.”

Here again this Midwestern legend took on a life of its own, “extending beyond the confines of the bunkhouses” and taking on a quality of “lumber camp lore” not unlike the tale of Paul Bunyan. Today, Hollars writes, the Hodag lives on, reincarnated year after year by Rhineand’s former mayor, Jerry Shindell, who plays Gene Shepard at the annual Oneida County Fair. To boot, the Hodag was recently added to J. K. Rowling’s new edition of Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them. Wisconsin’s lumberjack lore, as it turns out, lives on in the Wizarding World of Harry Potter.

Jacob A. Bruggeman is an associate editor of the Cleveland Review of Books.