by Paul Mariani.

Slant Books, 2019.

Paperback, 80 pages, $11.

Reviewed by Daniel James Sundahl

The weeks in the Christian liturgical calendar outside the major festal seasons are numbered in ordinary time, First Sunday, Second Sunday, and so on, not because the days are common but because the days are meant to be part of an ordered life, still watchful, still expectant, still directed, and still mysterious.

The liturgical color is green, which symbolizes growth. To sit in church on any one of the ordinary Sundays is read Scripture and remember how Christ’s life in ordinary time changed the lives of everyone with whom he interacted. It also means to live daily in faith, each day an ordinary time of growth when we use our hearts to explore everyday, ordinary sacredness.

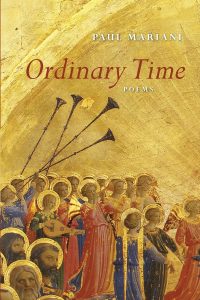

It seems wise to mention this because the parabola-like curve of Paul Mariani’s poetic career begins with his first book of poems, Timing Devices, 1979 (the cover of which displays a Moser wood-cut image of an heraldic angel), and arrives now with this new book and eighth collection of poems, Ordinary Time, the cover of which is a Fra Angelico image of “Paradise.”

What then might be ordinary in time with the introductory poem, “De Profundis”? We know by analogy that the title references a prayer based on Psalm 130 and can be translated as “out of the depths.” And to what degree is the making of a poem akin to ex nihilo, something out of nothing, out of the depths? The poet begins with “A blank slate, an empty canvas,” staring at that blank white page as if on the rubber roller of the old Olivetti. There is nothing there at this moment in ordinary time, but the poet asks us to consider whether the moment is also not unlike “the Creator God who once stared / … into the darkness covering the face, if face / it was, given the way the language works— / or doesn’t— …”

“De Profundis” bears not only reading but re-reading and even, well, a chant, reflecting eternity in its echoing sounds. Even in ordinary time a switch can be turned, and there will be light and where “nothing was” comes the “trumpet sound of sound itself.” Ordinary time does not, after all, mean nothing special or distinctive. Think of it this way: the Gospel reading for the Second Sunday of Ordinary Time usually features Christ’s first miracle, the transformation of water into wine at the wedding at Cana, something ordinary made into something extraordinary.

Consider three poems from the first section of Ordinary Time: “High Tea with Miss Julianna,” she “aged two / and a half and her grandfather, sixty-four.” It’s an ordinary moment in domestic time with “good manners … being understood between / the Professor and his finical little Queen.” And so high tea hums along as they confer about the best way “to pick the naughty dirts / from between their toes,” or which of her “many skirts / her dolly … should wear.” This, then, on a “Sunday afternoon at summer’s end, / sweet credences of summer”; the poet grandfather with his granddaughter as a little girl “who would not be little long.” It’s ordinary time during the year, of course, but also a time of growing, a living out of our faith in ordinary life adorned with a certain solemnity sacred to the heart.

Mariani follows with “Miss Julianna Revisited Twelve Years On”; she has not been little long. Miss Julianna has painted a landscape, blue sky and seaweed, thin brushstrokes for whitecaps and two faceless figures: a man with graying hair, a monochrome blue tee-shirt, and the other, that little girl in a lavender two-piece bathing suit.

So ordinary this child’s painting but the poet’s response in this ordinary moment of time is breathtaking:

Somewhere, he hopes, a world much like the one

his granddaughter has painted here exists,

a world no one can ever tear from them.

And, if not that, oh, if not that, then at least a world

where he can always hold her in his heart.

The “quotidian” occurs every day and is mired in mundane details, but it is also achingly human. As the poem turns at the end, the task is to take the little things in life that are normal and infuse those little things with the realm of the holy, and the loving sociality of the family a prototype for heavenly sociality.

Or it could be argued that the mundane, the ordinary is “a simple fragment / of something bigger, something it seems now heaven sent.” The fragment is a stone given to the poet by his grandson but which he thinks of as a “kind / of currency, money in the bank, something the very ground / had yielded up this day, anno domini … ”

The reader has in this slight poem, “The Stone My Grandson Gave Me,” the narrative of the grandfather and his grandson on a simple walk toward church, a small journey during which a simple thing becomes memorable. A small stone becomes for the grandfather “a thing turned diamond before [his] eyes” but placed in the context of “this day, anno domini,” to which one should add “nostri Jesu Christi” which would enlarge this ordinary quotidian moment with another time dimension, the year of our Lord.

There’s a slight shift in emphasis and tone in the second part to this collection. The poet’s own grandfather is the emphasis in the first poem, “Mexico.” It’s April 1916 and the grandfather is part of an army expedition “going after Villa.” It is ordinary time in history, of course, but for the poet it “floats as in a dream, the language strange, / and those who live there stranger” because what comes forward in ordinary time are other soldiers “awakening to another / twilight nightmare: Okinawa, the Chosin / Reservoir, Khe Sanh and Kuwait’s smoldering oil fields … one more benighted knight / sent out to make the world safe …”

There’s poetic discussion also of growing up on East 65th in New York City, and the time is 1945. He is standing with his brother Walter who “rifles through / a box of stale cupcakes the grocer has just / tossed into the ashcan” while his brother, the poet, grabs an empty whisky bottle “and there’s a black gap / where Walter’s front teeth were.” In ordinary time there’s always in time a world long gone but the scenes from that world long gone still tense the present with the damage done, wars and whiskey bottles and blood gushing out, and from which somehow we must find some kind of atonement.

In “Mothers’ Day, 2019,” a closer time in history, the poet and his wife are “headed north up 91.” His wife, a mother, has asked the family “to remember something special about [their] mothers.” He recites the time in which his mother, “God rest her soul,” stood up to his father, which, he says, took courage. He meant, however, to tell “a funny ha ha story,” but “suddenly [he] was weeping / and [his] grandkids were hugging [him].” What he remembers in ordinary time is the “sense of dovelike comfort that seemed to blanket [him].” And here’s the phrase illuminating how the sacred intersects the quotidian: “driving home / … the rain seemed to caress the maples / all along the highway, each leaf and bush / and blade of grass now blazing with grace.”

With time comes age and with age a certain fragility, or what the poet calls in the first poem of the third part to the collection, “shifting sands.” Two poems bear special attention. In “The Sick Man,” the narrative suggests the poet is recovering from anesthesia: “… it was a long way yet / and the narrow passage was dark / but there was light dim and hovering ahead.” It occurs every day in hospitals and for the most part is again as ordinary as that word “quotidian,” which one can come to love too much. But for our poet, the awakening is to realize that “he knew what being on the edge of life / was like now and he wanted life wanted / breath air light love … / to behold once more the blossoms / on the ancient catalpa in his back yard.”

That poem and the following “Coming Back from the Dead” are remarkable in their balancing emotion with spirit, simplicity and ordinary with the placid beauty of prayer. “So, where’s this going?” the poet asks, “this nightmare scene that will not let be me be,” “this fine-tun[ing] my sick brain.” Well, from that beeping blinking world of a hospital operating and recovery room, the poet imagines a “flicker of what [he takes] to be / an eastering light … me, there among the crocuses, / all three of them, and all a lovely purple.”

The final section to Ordinary Time consists of eight poems, the first of which is a “good Samaritan” experience again in ordinary time. “Eileen and Me” on the way to Amherst and a local Jewish temple. Along the way they come upon a “car stopped, lights dimmed, / stranded at a crossing like some lost sheep.” Inside is a woman in her eighties; she is lost, but all of this stopping is taking “precious time,” and the poet “wants to get a move on” and hear some good Jewish jokes rather than calming the old woman “and get her safely home.”

But then it “dawns” on him what he’s just witnessed “there on a dark road among / the shadows and the stark maples.” In ordinary time, a “random act of kindess” and heartfelt and blessed again and this “loving your neighbor / as yourself,” someone “as lost as [his] sorry self.” So what is out there, yet, for the poet to find in ordinary time? Replacing “Timor / mortis conturbat me … the fear that winds and unwinds” with an upward “gaze: / those blessed, dancing round and around in that circle of praise.”

All, after all, is still out there waiting for the right receptive moment in ordinary time, “oh God / it [has] to be out there somewhere / still waiting for [him] to find it.” The bookend poem to “De Profundis” is “What Happened Then.” The poet invites us to join the “few of us in that shuttered room, / lamps dimmed, afraid of what would happen / when they found us …”

Two have come back from Emmaus, another moment in ordinary time celebrated on an ordinary Sunday. “And now here he was.” And what “they” felt in ordinary time was “a calm.”

For this is what love looks like and is

and what it does. “Peace” was what he said,

as a peace like no other pierced the gloom

And descended on the room.

So we should note that in ordinary time one can find one’s self caught up in time—the mystery of Christ—and more deeply into sacred history, the goal of which is to know at last “what love looks like” and “what it does” in all the “ordinary time” through the year when something sacred pierces the gloom.

Daniel James Sundahl is Emeritus Professor in English and American Studies at Hillsdale College where he taught for thirty-three years.