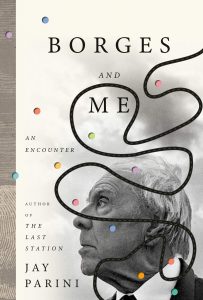

By Jay Parini.

Doubleday, 2020.

Hardcover, 320 pages, $27.95

Reviewed by Jerrod A. Laber

We’ve all answered the question at some point about those famous individuals, dead or alive, that we would most like to have dinner with if given the opportunity. Imagine then being a writer, or an aspiring writer, and getting to spend an entire week with one of the twentieth century’s greatest literary talents—and not realizing it. This is the premise of poet and novelist Jay Parini’s 2020 book, Borges and Me: An Encounter.

In 1970, Parini had received his undergraduate degree from Lafayette College and moved back into his parents’ home in Scranton, Pennsylvania. Surveying his options of either staying in Scranton or heading off to Vietnam, he settled on a third option of leaving the United States altogether and pursuing graduate studies in Scotland, at the University of St. Andrews, with the goal of being a professional writer, despite, he admits, “no demonstrable talents or experience.” Shaken as many of his generation were by the heavy toll exacted by the war in Vietnam, he sought to escape the “safe, simple, unquestioning life” and the “fatal lethargy of ‘normal’ life” in northeastern Pennsylvania.

Dodging both his mother and the local draft board, Parini arrived in Scotland with all of his anxieties still intact. The war still weighed heavily on his mind, exacerbated by the forwarded draft letters he received and the fact that his best friend from back home was actually in Vietnam, and he struggled to sleep and find his footing both as a student and writer.

Once in Scotland, wrestling with his poetry and his academic advisor over what his research agenda would be, Parini connected with Alastair Reid, a poet and translator who also wrote regularly for The New Yorker. It was through Reid that he would rendezvous with the subject of his story, Jorge Luis Borges, the Argentine short story writer, poet, and essayist, as Reid hosted Borges at his home while working on some new translations of Borges’s work.

The story of Parini’s encounter really gets going when Reid is forced to abscond to London for a week to care for an ill relative. Thus, Parini found himself looking after the elderly Borges, a man he had just met who was also blind (Borges suffered from a hereditary degenerative eye condition).

Despite being a student of literature, Borges was unknown to Parini at the time. Of course, he can be forgiven for this, for although Borges had been publishing vociferously since the mid-1920s, he was a relative unknown outside of Spanish-speaking literary circles. It wasn’t until Borges won the Prix International, an award he shared with Samuel Beckett, in 1961 that he garnered any international acclaim. It was in the early 1960s that Borges’s work was first translated and published in English.

Oblivious to all of this, Parini begrudgingly prepares to care for Borges for a week, complaining that a “blind old man is never independent. He’s the opposite of independent. And I could only begin to imagine the ways in which Borges might depend on me.” Unbeknownst to anyone, Borges would coax Parini into taking him on a tour of the Scottish Highlands.

I don’t want to diminish the significance of the personal struggles that Parini was going through at the time. The book is about more than simply his encounter with Borges, such as how the experience was a formative one early in his career that would give him a certain amount of peace about the direction his life was heading. But the great contribution of this book is how adroitly he gives the elder Borges a personality.

Borges was an enigmatic person. He felt a compulsion to write but claimed to not really have much to say or feel worthy of serious consideration. He said he knew nothing about politics, but was never shy to offer a political opinion. He wrote a famous short piece of fiction titled “Borges and I” where he proffered the differences between Borges the writer and Borges the man:

The other one, Borges, is the one things happen to … I hear about Borges in letters, I see his name on a roster of professors and in the biographical gazeteer. I like hourglasses, maps, eighteenth-century typography, the taste of coffee, and Stevenson’s prose. The other one likes the same things, but his vanity turns them into theatrical props.

The stories that Parini recounts rounds out Borges the person, his temperament, giving the reader insights into his personality that couldn’t even be gleaned from reading Edwin Williamsons’s definitive biography, Borges: A Life.

The Borges presented by Parini is not that dissimilar from the stereotypically eccentric, elderly uncle or grandfather that many people have in their lives, if that person also happened to be a literary titan: the man you are often having to excuse in polite company, but for whom you otherwise feel a great bit of affection and who actually possesses a great deal of wisdom.

At Parini’s first meeting with Borges, before their excursion together through the Highlands, Reid was having a get-together at his home for a small group. Parini recounts Borges requesting some fresh air and a walk, only to storm off ahead of the group to the edge of the North Sea, where he stands and bellows from memory the words of the old English poem “The Seafarer,” in the original Anglo-Saxon.

Early on in their journey, Parini describes Borges’s less-than-polite manner of consuming breakfast: “He gobbled the food with abandon, splattering his tie, and the others in the breakfast room … looked on with horror.” They soon after stopped off in a local library, one of the many gifted to various communities by Andrew Carnegie, where Borges spoke of the books and the stacks in terms similar to what he wrote in his famous short story, “The Library of Babel.” Exasperating the librarian, Borges said things like “the library is a sphere whose center is everywhere and whose circumference is inaccessible.” Parini sought to inaudibly express his regret for Borges’s eccentricities. And then in the next instance, we are apprised of Borges’s quickly recurring urge to relieve himself—something which happens to most men of advanced age—along the side of the road against the tire of Parini’s car.

It is in these instances and others, whether it’s Borges discussing the Pictish origin and proper pronunciation of the word “scone” or his unrequited love for Norah Lange, another Argentine author who eventually married one of Borges’s literary rivals, Oliverio Girondo, that Parini provides in Borges and Me a very human rendering of a man who has for many assumed a nearly mythical stature. And not human simply in that we understand Borges’s motivations or his feelings, but because we are also able to understand and feel his vulnerabilities, both physical and emotional.

We are able to see ourselves in that car riding along with them, or in those hotel rooms, and feel that we really know Borges, because he was not just one of the most influential writers of the twentieth century, but also an old man with recognizable, slightly annoying but otherwise endearing quirks and habits, worn down but not defeated by the inexorable march of time. Parini’s book ultimately triumphs as a “refraction and reconsideration” of “Borges and I,” as he puts it toward the end, giving readers an unfiltered and unadulterated look at both the Borges who liked the prose of Stevenson and the taste of coffee, and also the one who was written about in the papers.

Jerrod A. Laber is a writer and rare book collector based in the Washington, D.C. metro area, but he was born and raised in Appalachian Ohio. Previous work has been published in the Independent, 100 Days in Appalachia, the Columbus Dispatch, and the Orange County Register, among many other outlets.

NEH Support

The University Bookman has been made possible in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities. Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this article do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.