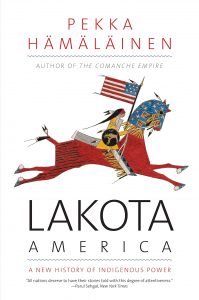

by Pekka Hämäläinen.

Yale University Press, 2019.

Hardcover, 544 pages, $35.

Revivewed by Santi Ruiz

On this year’s Indigenous People’s Day I encountered a curious phenomenon. My social circles are largely college-educated, left-leaning Gen Zers and Millennials, whom I assumed would be most likely to celebrate indigenous people as an underrepresented and integral part of the American fabric. Opening Twitter and Instagram, however, the zone was flooded with variations on the pastel infographic aesthetic that showcases one’s excellent politics. One wag’s tweet captured the dynamic: “hope everyone had a good time partaking in that beloved Indigenous People’s Day tradition: posting online about Indigenous People’s Day to own your dad.”

This state of affairs highlights the declining role of Native Americans in what Ross Douthat has called the American imaginarium. For most of the nation’s history, Native Americans figured largely in our self-conception: as the Pilgrims’ saviors, as retrograde savages, as Gaian mystics, opponents to progress, consummate trackers, and the last obstacle to the white man’s dominion over the New World. In the late 1800s, “Wild West Show Indians” became one of the country’s premier tourist attractions, by turns mawkish and genuinely sentimental.

It’s understandable why these forms of cultural representation, like the Cowboys and Indians television genre or the crude caricatures that once marked our sports teams, died out in an era more concerned with racial reconciliation. But it’s hard to point to more humane representations that have taken their place. What remains is generalized ignorance, punctuated by occasional invocations of Native Americans in a litany of oppressed peoples. Our culture seems satisfied by avoiding obvious offensiveness.

Jumping into this cultural void is Pekka Hämäläinen’s 2019 opus Lakota America, which presents the sweeping, unvarnished history of the Lakota tribe (often referred to as Sioux) from 1695 to today. Hämäläinen tells the deeply American story of a people at once oppressors and oppressed, tricksters who are themselves deceived, who over three hundred years traverse almost the entire continent.

Throughout the narrative, the Lakota remain stubbornly illegible to the white settlers they encounter. Hämäläinen does a sterling job of setting the stage by highlighting the gulf in societal and family life. The seven tribes that made up the Lakota had no centralized governance structure, and more than once the Americans suspect they have resolved tensions by cutting a deal with a regional leader who has no authority over other tribes. Society was tied together into “thiospaye,” groups of around twenty households, with each household bound through dense kinship ties to families within and without the thiospaye. These decentralized networks are systematically dismantled by the enforced move to reservations.

The Lakota begin in New England, but disease, settlers, war, and famine continually force them west. Crossing through the Midwest in the winter of 1703, the Lakota traverse a frozen lake, and discover that a tremendous herd of bison has been trapped beneath the ice. The natural refrigerator feeds them all winter. The book contains multiple moments of this kind of shocking, strange beauty, as when in a major conference women drop pieces of buffalo fat into their tipi fires at night, turning lodges into gigantic lanterns in a “sea of sparkling light.”

But the book’s focus is on the grand historical narrative, as the Lakota continually adapt to adverse circumstances. Over the course of the eighteenth century, the Lakota become a horse people. It takes generations, a huge expenditure of wealth, and day-long rides clinging onto wild and bucking horses until they break, but they do it, earlier than other tribes. It’s a technological cheat code. The plant biomass of the Great Plains may have been a thousand times greater than that of its animals: the horse unlocks all that energy and converts it to muscle power. Hämäläinen brilliantly documents the transition from a largely hunter-gatherer-farmer society, settled in Mississippi River valleys, into a fully nomadic one. It’s a staggering success while it lasts; by the late 1860s, the average family owns upwards of twenty horses. The empire these nomads build is rapacious; more than once, the Lakota are forced to move westward because they have looted the neighboring tribes out of existence and are therefore out of farmed food. Over several more generations, the Lakota shift fitfully west, until a series of visions reveals the Black Hills as their final home.

Hämäläinen treats with as much detail as he can their brutal war with the Crow tribes for control of the hills, though the historical record is largely confined to the extensive buffalo hide pictographs made each winter by tribal elders. Despite his attempts to demystify Lakota society, it is these intra-Indian interactions that contain the most mystery. We know that in 1835, Lakota chief Lame Deer shot a Crow warrior twice with the same arrow. We have little idea why.

One theory holds that Lame Deer is “counting coup”—a form of ritual point-scoring in battle that holds massive ceremonial and cultural weight among Lakota and Crow alike. For all its qualities, the book never quite unpacks this central societal behavior, describing it more as a game for the wealthy than as a driving feature of Lakota life. For those interested in this side of Great Plains culture, Jonathan Lear’s Radical Hope: Ethics in the Face of Cultural Devastation is a superb account of the practice among the Crow.

Hämäläinen spends ample time on the diseases that tore apart Native societies, and the sheer numbers are a useful reminder. Eighty percent of New England Indians died in a 1633 smallpox outbreak. Leading Massachusetts colonist John Winthrop sees it as divine intervention: “Gods hand hath so pursued them, as for three hundred miles space, the greatest parte of them are swept awaye by the small poxe, which still continues among them: So as God hathe hereby cleered our title to this place.” The various poxes overturn intra-native relations: at various points on their journey, the Lakota narrowly dodge or are less brutally affected by diseases that ravage the tribes already present in the land, making conquest that much easier.

But it’s the slower, more nuanced encounters between Lakota and settlers that get the most attention, and to which Hämäläinen brings the most clarity. For instance, the buffalo hide trade brings massive wealth to the Lakota. But as it scales, gender dynamics quickly spin out of control. As killing buffalo (a man’s job) takes much less time than skinning and tanning (women’s work), rates of polygamy skyrocket, with successful men taking on multiple wives, essentially as at-home laborers. The resultant spike in young, single men with little hope of finding a wife leads to macho posturing, widespread drinking, and violence.

In similar fashion, the advances of the steam train and of trading posts at first cement the Lakota position as rulers of the Plains. As the frontier pushes west, Lakota society becomes completely riven over how to deal with white intrusion, with the economic ties to the posts limiting the possible responses.

Well into the last years of the nineteenth century, the Lakota continue to mount spirited resistance to federal control. Little Big Horn and Wounded Knee both get ample attention, with Hämäläinen not shy to describe the brutality of warfighting on both sides. Wounded Knee in 1890 marks an end to the Lakota empire: many winter counts end for good there, and those that remain are a grim catalogue of suicides, domestic violence, and the herding of the tribes onto reservation land. Before the great leader’s death, Red Cloud puts it poignantly: “Think of it! I, who used to own rich soil in a well-watered country so extensive that I could not ride through it in a week on my fastest pony, am put down here … Now I, who used to control five thousand warriors, must tell Washington when I am hungry. I must beg for that which I own.”

Today, it’s hard to find remnants of the empire that once ruled the Mississippi, then the Great Plains, then the American Northwest. But it is as integral and vibrant a part of American history as any. If we Americans tend to confront our relationship with Native Americans by either whitewashing our story, or by recognizing them chiefly as an oppressed contingent of society, books like Lakota America offer us a third way: simply telling their particular, human story, one that is just as important as the story of European settlement and pillaging. If anything, reading Native history helps us engage with contemporary political issues more honestly: how, for example, the Indian Bureau’s bags of flour and sugar helped create the modern diabetes wave on reservations. Books like Lakota America help us begin to see our shared America, in all its guts and glory.

Santi Ruiz is a writer living in Washington DC. You can reach him on Twitter at @rSanti97.