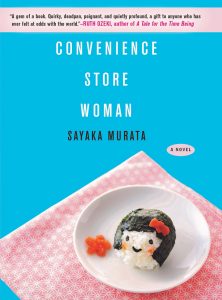

by Sayaka Murata.

Grove Press, 2019.

Paperback, 176 pages, $15.

Reviewed by Eve Tushnet

Keiko just wanted to do the right thing. Eager and goal-oriented to a fault, little Keiko Furukura found the world around her baffling, full of unspoken rules and incomprehensible barriers. As a schoolgirl she broke up a playground fight by braining one of the tussling boys with a spade. Why did people think that was so strange? They wanted someone to stop the fighting, and she did! Why did her parents keep hoping she would be “fixed”?

As Keiko grows, the world continues to puzzle her. People expect her to want things she doesn’t want, and feel things she doesn’t feel—like a preference for her own family’s babies over other people’s. Her difference is disturbing to those who love her; it’s a little disturbing even to the reader. (That spade is not the only time she considers the utility of violence as a solution to interpersonal problems.) Slowly she too begins to long to be “fixed.”

Then one day she finds herself wandering through a nearly deserted industrial area. “Overwhelmed by a sensation of having stumbled into another dimension,” a “ghost town,” she is so lost that when she sees the sign for “a pure white building” she runs toward it. This is Smile Mart: the first, and only, place Keiko will ever feel at home.

Sayaka Murata’s 2016 tale of a woman who becomes the perfect convenience-store employee, her whole body humming with the rhythms of the store, could have been a tragedy or even a grotesque. Instead it’s a strange romance, in which Keiko is the ingenue facing down societal disapproval in order to be with her fluorescent-lit, fully stocked beloved. Keiko, far from stalling out in life, has to grow and change in order to turn her early infatuation with Smile Mart into a mature love. Keiko’s voice, rendered in English by Ginny Tapley Takamori, is bright and curious, forthright and full of a kind of discount wonder. Convenience is a bit repetitive, perhaps too blunt in insisting that Keiko longs to be “a normal cog in society.” But on the rare occasions when Keiko reaches for metaphor, she shines: A baby’s cheek is “strangely soft, like stroking a blister.” She’s a little too chromium-plated to be sweet, a little too Teflon-coated to be gentle, and yet she’s a charmer and a delight. Her joy in the store radiates off the page.

For Keiko, Smile Mart was “the first time anyone had ever taught me how to accomplish a normal facial expression and manner of speech.… [T]here was a detailed manual that taught me how to be a store worker, and I still don’t have a clue how to be a normal person outside that manual.” The Smile Mart door chime is like “church bells” for her; “I have faith in the world inside the light-filled box.”

This feeling of homecoming in work is unusual in contemporary culture but not quite absent. We most often hear it when the worker has been through something terrible beforehand: After the chaos of addiction or an abusive upbringing, a job that offers clear rules and obvious ways to be of service comes as a refuge. I first encountered that metaphor in which everybody else has been given some secret handbook to life, which you are missing, in the Big Book of Alcoholics Anonymous. What gives Keiko Furukura her unique charm is that she has this refugee attitude without the chaos-wracked background that usually provokes it. She notes that she doesn’t have “the obvious type of anguish” that others might understand. (We have scripts even for our deviance.) For her, simply living in the world with the rest of us is chaos enough to flee.

Keiko delights in some of the most irritating features of modern work culture: the prescribed greetings, the daily recitation of the store “pledge,” the instructions on how to smile. (This is the only novel I know of with a scene illustrating the benefits of employer surveillance cameras.) She’s happy to apologize to customers for things that aren’t her fault. She’s adaptable, willing to gossip and complain since these actions seem to help her coworkers in ways she doesn’t fully grasp. She’s good at her job, and she doesn’t care if other people think you shouldn’t bother to be good at a convenience-store job.

Convenience Store Woman can present retail work as reverse Wonderland—a haven of sense in a world of absurdity—because Keiko’s life lacks some of the abusive absurdities of much low-wage work in this country. She works regular shifts announced in advance, without just-in-time scheduling or “clopens” or hours doled out and withheld seemingly at whim. The store is slightly understaffed, but this never reaches the point that it affects customers’ moods too much; there’s sometimes “rush” and scrambling, but not the chronic stress of a store that understaffs by policy. Although management is sometimes frustratingly focused on things other than the store, they don’t just ignore the rules or punish her for following them. Keiko has to live frugally, but she isn’t destitute. She doesn’t worry about having a roof over her head or enough vegetables to “heat-treat.” (Keiko cooks like a robot writing poetry.) She’s even able to support a dependent—a fellow misfit who turns out to be far more normal than Keiko, far savvier and far more unscrupulous. Smile Mart is her haven not only because it is so similar to many American workplaces, but because it is different.

The only problem is that Keiko is getting older. Her family and friends no longer accept her excuses for avoiding marriage or a more prestigious job. The pressure is increasing for her to fit in, find a mate—or at least get a job where she can choose how she smiles!

Keiko has acted like a people-pleaser, willing to conform to all the ridiculous things we demand as proof of normalcy. She’s acted like someone who cares about keeping up appearances. But Keiko Furukura is something stranger and more beautiful. She says “there wasn’t anything about myself that I particularly wanted to defend”—but after a life spent seeking only to be useful and unopposed, she takes her stand. She is abnormal and doing fine. She demands to be where she understands things; she demands to be with her beloved.

If the object of her love is unworthy of it, if it can’t return her devotion, if what it gives is so much less than what any person is capable of receiving—does that make her love silly? Does that make it sublime?

Eve Tushnet writes from Washington, D.C. Her most recent novel is Punishment: A Love Story.