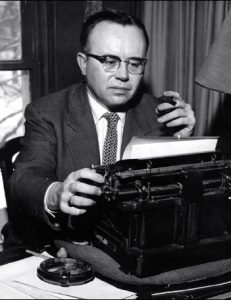

Classic Kirk:

Classic Kirk:

a curated selection of Russell Kirk’s perennial essays

A Note from the Editor

Russell Kirk once heard Winston Churchill “address a great crowd in Glasgow—on the eve of his return to power in 1951, as matters turned out. Witticisms, apothegms, telling anecdotes burst from his lips like bombs.”

In this book review for The Detroit News, Kirk takes the opportunity to examine Churchill’s rhetorical power and his foreign policy realism, particularly as a salutary guide for America.

Churchill: ‘Common Sense Incarnate’

Review of Winston Churchill’s World View: Statesmanship and Power, by Kenneth W. Thompson, in The Detroit News, April 27, 1983.

Ever since World War II, Sir Winston Churchill’s reputation for courageous statesmanship has stood even higher in the United States than in Britain. In postwar Britain he was a partisan leader; in America, he could be admired without regard to party.

Four decades after Churchill’s finest hour, it is possible to examine the statecraft of the great prime minister with dispassion. This Kenneth Thompson does—temperately but admiringly. His study offers serious readers the opportunity to examine the present world perils in the light of Churchill’s realistic foreign policy.

One of the more important chapters of this valuable book is titled “Public Opinion and the Dilemma of Realist Foreign Policy.” In democracies, the author reminds, “Public opinion in the short run tends to be corrupted by purveyors of deceptively simple and attractive slogans and panaceas or by the influence of politicians who mislead by identifying their selfish interests with the aspirations of the whole nation.”

Churchill’s understanding of the uses of power, his attachment to the concept and the reality of the balance of power, and his hard-headed suspicion of the Soviets (vindicated by events) did not endear him to idealistic liberals. His demand for “blood, sweat, and tears” was not a popular line to take in a sentimental and comfort-loving democracy. How was it that Churchill contrived to win over public opinion repeatedly?

Why, through audacity and rhetorical power.

Once I heard him, a bowed and corpulent old gentleman, address a great crowd in Glasgow—on the eve of his return to power in 1951, as matters turned out. Witticisms, apothegms, telling anecdotes burst from his lips like bombs. He seemed common sense incarnate. Liberals and Laborites might denounce him as an antique figure from the past century, a pillar of detested imperialism. No matter: In an hour of crisis, he was John Bull, “the true-born Englishman,” popular with the crowd—yet John Bull endowed with wit, shrewdness, and much experience in great concerns.

Like Burke and Disraeli before him, Churchill disdained ideology and utopianism. Like them, he knew that much was to be learned from history. His foreign policies and his understanding of international affairs were rooted in custom, convention, and a realistic apprehension of human nature.

Yes, Professor Thompson’s study is highly relevant to our present international discontents. His chapter on “The Disarmament Dilemma” reminds us how history repeats itself—although always with variations. “We learn from history that we learn nothing from history,” Hegel wrote—not that history is valueless, but rather that we ignore its lessons. How true this is of perennial arguments about disarmament.

In 1950, some influential people on either side of the Atlantic demanded that all great states agree never to resort to atomic bombs. Churchill replied to their argument that no nation should use that bomb unless it has first been employed against them.

“What this would mean in practice, he declared, was that nations would agree never to fire unless they had been first shot dead. ‘That seems to me undoubtedly a silly thing to say and a still more imprudent position to adopt. Moreover, such a resolve would certainly bring war nearer. The deterrent effect of the atomic bomb is at the present time almost our sole defense.’”

In 1948 and 1950, Churchill said what ought to be obvious enough today:

“It is indeed a melancholy thought that nothing preserves Europe from an overwhelming military attack except the devastating resources of the United States in this awful weapon. That is at the present time the sole deterrent against an aggressive Communist invasion. No wonder the Communists would like to ban it in the name of peace.”

The “old diplomacy” so vigorously represented by Winston Churchill was better calculated to maintain the peace than the idealistic “new diplomacy” of the liberals, Thompson concludes. Woodrow Wilson’s notion of “open covenants, openly arrived at” always was an illusion: It is needful merely to glance, for evidence, at the daily performances in the theater of the absurd on the floor of the UN General Assembly. As Churchill put it, “Under conditions of the fullest publicity nothing of any importance could ever be done.”

Strongly influenced by the teachings of the late Hans Morganthau, Professor Thompson presents a salutary dose of diplomatic realism—both Churchill’s specific and his own. Liberal diplomacy is failing us gravely, Thompson writes; we confront a crisis brought about by “the inadequacies of parliamentary diplomacy, the weakness of American concepts of diplomacy, and the evils that arise from the authoritarian practice of Soviet diplomacy.” Unless we Americans can rise to a world view comparable to Churchill’s, once more the failure of diplomacy may end in general war.

Classic Kirk:

Classic Kirk: