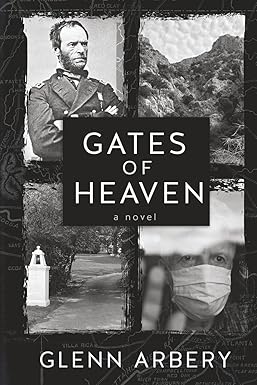

By Glenn Arbery.

Wiseblood Books, 2025.

Paperback, 554 pages, $20.

Reviewed by Chilton Williamson, Jr.

Gates of Heaven is Glenn Arbery’s third novel; it is also the last in a trilogy that, reckoning by the publication dates, was a labor that took a decade to complete. The first two volumes are set in the fictive town of Gallatin in Professor Arbery’s native Georgia, while in the third the story has moved to Lander, Wyoming, where the author is President Emeritus and Professor of Humanities at Wyoming Catholic College, although toward the end of the book it reverts to Gallatin with which the characters have retained family and social connections. Arbery’s South is the post-New South, neither Mark Twain’s Old South nor Walker Percy’s New one. Six years ago, at the end of my review of Boundaries of Eden, the middle novel which ends at the precipitous edge of Old Faithful in Yellowstone Park 150 miles north of Lander, I wrote that, as a resident of the Cowboy State (pop. 560,000-odd, area 97,000 square miles) for nearly half a century, I looked forward to reading what the author would make of this new territory and the frontier Yankees who inhabit it. As it happens, the author’s focus is not on Wyoming but on the United States in the time of the Great Epidemic and the Biden v. Trump campaign, just as the events in Bearings and Distances, the first volume, occur during the summer following Barack Obama’s election to the presidency: historical circumstances that Arbery makes it a point to stress.

Mr. Arbery is a highly contemporary novelist; in this he reminds me powerfully of the late John Updike, best known for his portrayal of middle-class suburban life in the American Northeast during the second half of the twentieth century. His depiction of the United States in the twenty-first is both recognizable and compelling, though he does tend to over-do it (in his relentless specification of familiar commercial brand products, for instance) at times. Still, broadly speaking and in the essentials, Glenn Arbery has contemporary America down cold, the more so since the cultural variations between North and South are far from being as marked as they were even fifty years ago.

Mr. Arbery writes long books (“big-boned,” as he says): each of the three novels exceeds 500 pages, while his narratives are correspondingly intricate and complex and the cast of characters both wide and diverse, to the point that it is difficult at times to keep track of them. This makes summarizing the first two books in a manner sufficient to provide an adequate introduction to the final one nearly impossible in a relatively short review. Suffice it to say that the main characters, Braxton Tecumseh Forrest and Karl Guizac (an unusual surname: could Arbery perhaps have borrowed it from Flannery O’Connor’s character in “The Displaced Person”?) remain in their roles as patron and patronized, Forrest having financed a regional online journal named Sage Grouse for Karl (formerly Walter Peach, a once-promising poet who in his first marriage backed a car over his small son) after having facilitated the transferal of his wife Theresa and their family to Wyoming to escape a murderous international drug cartel in Gallatin.

When the local school system shuts down with the outbreak of Covid-19 in Lander, Walter arranges for his son Jacob to continue his historical studies over Zoom under the tutelage of Forrest, who assigns him a hundred-page essay to write on the subject of General William Tecumseh Sherman, the scourge of Atlanta during the War Between the States. Jacob, appalled by what appears to him to be the magnitude of the assignment, quickly becomes fascinated by Sherman whose personality seems at times to usurp his own, causing him to fall intermittently into what Walker Percy might have called “fugue states” in which he imagines Sherman at various critical stages of his life and his military campaign in Georgia. Jacob, like his parents a fervent Catholic, sees “in the face of William Tecumseh Sherman….what it looked like when God unleashed his absence on the world.” Sherman, whose wife was a pious croyante and whose son became a Catholic priest and committed suicide in middle age, despised religion and was a notorious philanderer all his life.

Walter himself is stricken by an acute case of Covid and flown to Salt Lake City, where the doctors put him into a coma to save his life. As he is unable to edit the journal, now highly successful within Wyoming, Forrest travels with his wife Marisa to Lander to maintain it. Unconscious and on a ventilator, Walter experiences the first of a progression of “dream experiences” in which he is facing a judge who explains, “What we are about today…is a provisional inquiry. We’re looking at your qualifications for your upcoming death, should it occur. As I say, it’s provisional, and you might need to repeat the procedure should you survive and fall back into your habitual pattern of life….You didn’t make any provision for an advocate.” In the course of these visions, Walter comes to realize that his entry into Heaven is conditional on his forgiveness of Sherman and his brutal campaign against the South, and on Sherman’s salvation as well as his own. The Forrests’ arrival in Lander coincides with a family crisis in Georgia, where their son-in-law has been cheating on his wife and Hermia Watson—a black woman and professor of black studies, Braxton’s former lover, and the founder and proprietor of a home for pregnant unmarried girls—is under assault by the local pecksniffs. Having stabilized Sage Grouse, Forrest returns to Gallatin accompanied by Jacob as his student and companion, and the story mutates temporarily into a post-modern Southern Gothic tale.

Jacob, in the course of his Sherman research, peruses a vast number of biographies, histories, and memoirs, while writing a series of essays concerning what he has read that he forwards to Forrest and gives to his father to read. Both men are astonished by the intellectual sophistication of the boy’s mastery of his subject and by the superior quality of his prose style as he recounts critical moments in General “Uncle Billy’s” campaign, and also his love affairs. The affairs cause Walter to wonder just how far his son’s relationship with his girlfriend in Lander has progressed, though Jacob’s obsession—amounting almost to possession—with Sherman concerns him even more, as it does the girl herself. The chapters regarding Sherman are, indeed, some of the best in the book. A particularly striking and imaginative one describes a meeting between a young Atlanta woman who produces a pistol in the course of the private interview she has requested with the General, an incident to which Sherman’s response is fatalistic. He had always supposed, he reflects calmly, that he would die in a manner similar to this one. For Glenn Arbery, William Tecumseh Sherman was not only an historical monster: he epitomizes and symbolizes what America has become in the age of Obama, Biden, and Trump.

Gates of Heaven is one Southerner’s attempt to come to terms with the War, the Yankee victory, the destruction of the traditional South and its replacement by the anti-traditional, industrial, and hyper-modern culture of the North, and his own anger and resentment. It is a highly original and imaginative story whose supernatural aspect reveals itself gradually through Walter Peach’s “dream experiences” as he lies in a coma in a Salt Lake hospital. In his “Acknowledgements” at the end of the novel, the author explains that, “Decades ago, I considered writing a long poem about this man [Sherman] who waged war on a civilian population—a prelude to the practices of the twentieth century—but instead, I made him a presence in my three novels, feeling that he remains the necessary antagonist, not just for the Old South and the Confederacy, but for the self-understanding of our own times.” Still, he acknowledges that, “My Sherman is fictional, an interpreted and surmised consciousness filtered through the sensibilities of his narrator in the novel, young Jacob Guizac, but also inevitably through my own.” Arbery adds, intriguingly and with reference to Walter Peach’s dreams, or visions, that he owes them to “my remarkable conversations with Jason Shanks, now president of the National Eucharistic Congress, and to his account of his experience with Covid-19 during almost exactly the same time period that my novel covers, and over a period of weeks in an induced coma.”

Gates of Heaven is as remarkable a novel as it is a compelling one; there is, quite simply, nothing that I know of in American literature to which it may be compared. It is also a worthy and satisfying conclusion to a fictional trilogy as distinguished in its component parts as it is in the final one.

Chilton Williamson, Jr. is the author of After Tocqueville: The Promise and Failure of Democracy.

Support the University Bookman

The Bookman is provided free of charge and without ads to all readers. Would you please consider supporting the work of the Bookman with a gift of $5? Contributions of any amount are needed and appreciated!