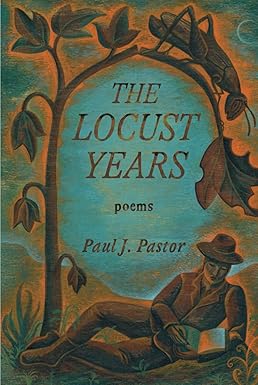

By Paul J. Pastor.

Wiseblood Books, 2025.

Paperback, 129 pages, $20.

Reviewed by Sarah Reardon.

“Verily, verily, I say unto you, Except a corn of wheat fall into the ground and die, it abideth alone: but if it die, it bringeth forth much fruit.” – John 12:24 KJV

The above verse is the epigraph to Fyodor Dostoevsky’s masterpiece The Brothers Karamazov, and its significance throughout the book is especially revealed by the loving and wise Father Zosima.

In one of the elder Zosima’s last instructions to his beloved Alyosha, Dostoevsky’s hero, he cites John 12:24 and tells Alyosha that “everything is from the Lord, and all our fates as well… Life will bring you many misfortunes, but through them you will be happy, and you will bless life and cause others to bless it—which is the most important thing.” Similar instructions and ideas repeat throughout the whole book: through suffering, there will be joy.

As I read Paul Pastor’s recent collection of poems, The Locust Years, I couldn’t help thinking of Dostoevsky and his character Alyosha. Though Pastor takes his own epigraph from the poet Geoffrey Hill and his title from the biblical prophet Joel, Dostoevsky’s epigraph might well be Pastor’s. For like The Brothers Karamazov and, in fact, like much of the Christian literary tradition, The Locust Years revolves around the pattern of death and resurrection, of despair and hope, of suffering and joy.

Sally Thomas rightly notes the prevalence of paradox in Pastor’s work. Pastor’s central paradox is the paradox inherent in the prophet Joel’s words from which Pastor draws: “I will restore to you the years the locust hath eaten, the cankerworm, and the caterpillar, and the palmerworm, my great army which I sent among you.” It is the paradox of all botanical life, as articulated by the apostle John and repeated by Dostoevsky. It is the paradox of a tomb—in itself a grim image—newly empty.

Pastor’s collection moves through the seasons, beginning with spring. As it does so, it moves, too, through the process of “fall[ing] into the ground” in death and then bringing forth fruit. Along the way, whether through blank verse, sonnets, hymn meter, or a metrically-informed free verse, Pastor presents the wonder of this death and resurrection phenomenon in the natural world and in the world of human relations. And those two worlds, for Pastor, are closely intertwined: as he writes of the woods in one sonnet called “Haunting”: “I’m bound / as ever to the clampings of this place, / heady with the loaming of the ground, / heavy with the misting of the grace.”

Though very readable, Pastor’s poems are often enigmatic. I had to read several of his poems multiple times just to begin to understand them. To my mind, this is to Pastor’s credit: good poetry is not, to use Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s term, a “cheap grace” that asks no time nor deep reflection but only stirs up surface-level emotions. Rather, good poetry, like any good gift, should require something of its reader or receiver. Pastor informs his reader in his introductory letter that the book revolves around a riddle of sorts: a common word that appears nowhere in the poems but with which all the poems are concerned. I think I may have to read the collection again before I publicly venture a guess at what that word is, but I wouldn’t be surprised if it had to do with the paradox of death and resurrection.

For all the weight that Christianity and its paradoxes pull in the Western poetic tradition, you’d think that the theme of death and new life would be a rather tired one. And perhaps it is, at least in the work of more amateur poets than Pastor. But Pastor shows that the great paradox of the empty tomb is, in truth, an indefatigable one: he unravels a hundred delightfully particular strings from the awfully abstract words “death” and “resurrection.”

For instance, in “Under the Perseids,” Pastor maintains that

…The heavens twitch and fall

By crumbs and sparks, each burning like a breath

With no hope of return. They teach us all

That every light we see is something’s death.

But perhaps stars are not an uncommon image of mortality. Pastor’s work ranges much farther in its embrace of the strange and particular: in “Because I Thought That Hope Was Not For Me,” the speaker likens hope to a rodent who “nest[s] and nuzzle[s] me.” In “I Must Become as Beautiful as Kelp” the poet declares what his title suggests: a wish to become, like kelp, “Held down, pulled up… / Until I rise, and I am given to the beach.” In “Sawgrass Song,” the speaker learns a “gifted grieving” from a landscape of sandpipers, briny seawater, dead crabs, and sawgrass. In the title of another poem he asks, “Surely, a Well Feels Like a Wound to the Earth?”

In other poems Pastor employs more conventional Christian imagery, but he does so without surrendering to cliché. In one of my favorite poems in the collection, “The Noise of the Groat,” Pastor writes of youthful years gone by as a “kern of tears / whose root is love, which splits the barley’s skull.” He ends the sonnet thus:

O Home, you field of bounty and of grief,

Make deep your furrows under God’s flint plow,

And may you not fail the unshielded leaf

No one may guard, which yet is sprouting now.

And by rich git, and by my hard-ground bone,

Grant that no seed which dies remains alone.

In his prayerful request that the helpless leaf be not left hopeless and that the falling seed be not left fruitless, Pastor’s faith shines forth.

His faith is not naive. It is a faith that has been tried repeatedly and has come to grips with the fact of the “vanity, vanity” sung by the Preacher in Ecclesiastes. As Pastor declares in the title poem of the collection: “My son, there is no fairness in the years, / No paid deserving. Nothing but the gift / Gone forth, gone sideways.” This life is one without fairness; though a gift is given it is skewed. And still the poet can proclaim a few stanzas later:

But there will come an autumn day when highway lines

Point home, return you to the gravel drive

Cut in the hedge, the wet road filling, emptying,

Pulling you to me with highway lines,

And I will trot to greet you, all the swarming years

Behind us, run like you would when I pulled in view

When we were younger, you a toddy boy, I less grizened wild

From all the wrack and weeping of the locust years.

Here the conviction of things not yet seen allows Pastor to envision a joyous reunion not unlike that of the prodigal son and his father. As the poem reaches its end the speaker envisions pressing and straining to make cider alongside his son “to toast our locust years.”

And that, ultimately, is what The Locust Years invites us to do: not to deny the “wrack and weeping” of suffering and death but to look forward to the day when, resurrected, we will toast to them.

Sarah Reardon’s first collection of poetry, Home Songs, was published by Wipf and Stock in 2025, and her essays have appeared in First Things, National Review, Plough, and elsewhere.

Support the University Bookman

The Bookman is provided free of charge and without ads to all readers. Would you please consider supporting the work of the Bookman with a gift of $5? Contributions of any amount are needed and appreciated!