Classic Kirk:

Classic Kirk:

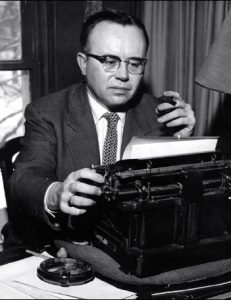

a curated selection of Russell Kirk’s perennial essays

A Note from the Editor

Those of you who like to visit used bookstores will especially enjoy this piece, “F. Marion Crawford: Grand Romantic.” Russell Kirk was “astounded” to be asked to write a foreword to An F. Marion Crawford Companion considering that he had never mentioned Crawford in any of his writings. But for fifty years Kirk had been collecting works by that author and recalled exactly where he had obtained each book in vivid detail. In this little-known piece recently discovered in the archives, Kirk pays tribute to the strong influence that Crawford’s historical Romances and novels exerted upon him, particularly in his travels and his own fiction.

F. Marion Crawford: Grand Romantic

Foreword to An F. Marion Crawford Companion by John C. Moran (Greenwood Press, 1981).

This present curious circumstance—that I should write a preface to a monograph about Francis Marion Crawford—might provide Arthur Koestler with another incident for his slim book The Roots of Coincidence, if ever Koestler favors us with an enlarged edition. Although Crawford has haunted me for several decades, I never had expected to learn of an F. Marion Crawford Memorial Society, lodged in Saracinesca House, Nashville. Nor did I ever dream that a Mr. John C. Moran, previously (1978) unknown to me, somehow should sense that I am a Marion Crawford enthusiast (I never having owned this passion in the twenty-two volumes or the thousands of periodical pieces that I have published); nor that Mr. Moran should hit upon me, of all possible men of letters, for providing a foreword to his assessment of Marion Crawford. I am as much astounded as gratified.

Is this “coincidence,” then, some concitation of the backward devils? lt might convert into a solipsist a writer less orthodox than myself. Surely this cannot be coincidence merely—if, indeed, “coincidence” ever occurs at all. Perhaps from the very beginning of things it was ordained that Russell Kirk, small Romantic, should write something about F. Marion Crawford, grand Romantic. For half a century I had not fulfilled this ineluctable decree. I now must confess that despite my intellectual discipleship to Irving Babbitt and his classicism, by temperament I always have been a Romantic; and I was reared on Scott and Hawthorne. “Russell, you’re the last Romantic writer,” a friend said to me years ago, “and probably the greatest, because nobody else ever could have conjured Romance out of that god-forsaken Michigan backcountry where you live.”

That remark was kind irony; nevertheless, even allowing for the far richer materials that Crawford had to work upon, Francis Marion Crawford looms immensely taller in the realm of Romance than does the author of this preface. I have thought more than once of encroaching upon Crawford’s especial territories, Italy and Sicily, as settings for my own stories; yet I have refrained from any such incursion, not knowing those lands and peoples a tenth so well as Crawford did, and so fearing that my emulation might be ludicrous merely.

I observe, for all this, that anyone who follows in Crawford’s Italian footsteps still might pick up materials for a thousand Romances, even in the last quarter of the twentieth century. The Castle of Otranto still stands. One encounters in America a notion that “there aren’t any ghosts in Italy”; but some acquaintance with the old families of Florence (aye, even Florence, that most rationalistic of cities) will reveal that spectres continue to stalk palaces there—and to be much dreaded, if only because their reputed presence diminishes the proprietors’ rents. The hill-towns of the Apennine spine, for instance, are lonelier and more eerie than they were in Crawford’s day, many of them. . . . But I digress.

It would be presumptuous if I were to set up against John C. Moran’s study of Crawford any attempt at a critical examination from this typewriter. In this foreword, then, permit me merely to suggest Crawford’s subtle and almost occult influence upon some of us, though he has been dead for seven decades. My own odd experiences with Crawford’s books may be paralleled by the adventures and discoveries of other folk.

I first came upon the name of Francis Marion Crawford just over half a century ago, when I was ten years old. My grandfather, a bank-manager of some intellectual attainments, possessed two large oaken cases of books, with leaded-glass fronts, surmounted by pillars and forming a permanent partition between his parlor and his dining-room. In one of those cases I happened upon a handsome illustrated edition of Via Crucis—which later I inherited, though it is lost now. My grandfather owned sets of Mark Twain, Charles Dickens, and Victor Hugo, and most of Sinclair Lewis’ novels; but otherwise there was little fiction on his shelves; and Via Crucis was the only historical Romance there. At once I read Via Crucis ardently—thereby enlarging my acquaintance with Eleanor of Aquitaine, whom previously I had known only through Dickens’ Child’s History of England—and the book fired my imagination. I have read it several times since.

Next I came upon some of Crawford’s ghostly tales, especially “The Upper Berth”—first, I think, in one of Dorothy L. Sayers’ anthologies. (My appetite for uncanny stories extends back to the age of seven.) But the public library in our town had none of Crawford’s books—rather strange, that, because it was a superior library; still, Crawford had been dead for twenty years by that time. Nor did our school library possess any of them.

Thus it was not until I was a high-school freshman that I came upon Crawford again. I happened to wander into a sale of old books at an auctioneer’s rooms. These books had constituted the good library of the oldest family in a neighboring town; the younger generation had sold their handsome inherited house and its contents—even to the family Bible, which my aunt was given free by the auctioneer—and had moved away to a sunnier clime. All these books were to be sold for ten cents apiece, and I picked up, among others, one volume of Crawford’s The Rulers of the South, admirably illustrated. (Somebody who didn’t know that any work extends to more than one volume doubtless had purchased Volume I before I got there). Not for many years would I find a Volume I to match my bargain Volume II. But that admirable second volume could be read in its own right; and thus it came to pass that F. Marion Crawford, as much as anyone, showed me the manner in which history should be written.

My college years elapsed, and my army years in desert and swamp, and my first years as a professor of liberal arts, before I found more of Crawford. Then, in 1946 I think, with a partner I bought the immense library of a long-dead justice of Michigan’s Supreme Court, Howard Wiest. Justice Wiest’s mansion, demolished thoughtfully some years ago by improvers, was the most handsome house in Lansing, and the oldest and strangest. Cobwebs hung heavy in every book-jammed room behind those shuttered tall windows. My short story “What Shadows We Pursue” was written, years later, with the Wiest house as its uncanny setting. Nearly all of those thousands of books were sold by my partner and me, for we had high hopes of becoming famous booksellers. But some few books I saved for myself, and one item I so reserved was the two-volume set of Crawford’s Ave Roma lmmortalis: Studies from the Chronicles of Rome.

Two years later, at Christmastide, I would be in Rome for the first time, as matters turned out—something I never expected when I acquired this set. I would make many more Roman expeditions, as the years passed, and always I would take Ave Roma lmmortalis with me, though the volumes weighed down my suitcase. I would come to know Romans of the sort that Crawford had known; I would talk with the last Duchess of Sermoneta, as Crawford had known an earlier Duchess of Sermoneta; indeed, I would be introduced to the last Duchess by the Scottish Earl of Crawford, her distant kinsman. At Ninfa, “a medieval Pompeii,” in the drained marshes below the Volscian Hills, the Duke and Duchess, the last of the Caecani, the most ancient Roman house, received me in their unique villa that had been a medieval palazzo publico; and on that occasion I thought of how this was the last of an old song which had been growing faint in Crawford’s time.

I still had not read most of F. Marion Crawford’s novels. But until I married at the age of forty-five, I used to spend most of my summers with my friends the Christies of Durie, at their lovely austere classical house of 1750, in Fife. The Christies had held Durie House and its rich lands since 1776, and had accumulated naturally enough a considerable miscellaneous library. Some of this collection, particularly that made by recent generations, was lodged in a long garret just under the leads—next door to the locked chamber, something of a muniment room, notoriously haunted by “Old Mr. Boofie with cobwebs in his eyes.”

And in that garret-library, cheek by jowl with shelves of occult lore and Theosophy (for my friend the laird had been a Theosophist once), I unearthed virtually the entire fiction of F. Marion Crawford—who, I think, had been an especial favorite with the laird’s mother. As the summers passed, I read those Romances in leisurely fashion, enjoying especially one of those not much known, The Heart of Rome—fascinating to me because already I had explored something of subterranean Rome. The underground chambers, dating back to ancient times, of the Conti Palace in part provided the inspiration for the Weem in my Lord of the Hollow Dark. Also I became acquainted with the Saracinesca trilogy. Crawford would have been delighted by Durie House, and in particular would have sought after Durie’s principal phantom, “Chillianwallah” Christie, the grandfather of my old friend the laird. Nothing at Durie ever affrighted me, I must admit: it was the jolliest of Scottish country houses.

My most recent strange encounter of the best kind with the books of F. Marion Crawford occurred in Grand Rapids, perhaps six years ago. A huge family library was being sold off, volume by volume; it was so large, indeed, that the people who purchased it leased a big disused bookshop and went into business with this library—which filled hundreds upon hundreds of stout shelves—as their whole stock in trade. I believe that this retail enterprise trailed on for two or three years.

It could not have been profitable, really, because the vast majority of the books were popular novels, published between 1885 and 1935, say. Until one looks over such a private collection, one does not fully understand how vast was the output of popular fiction before radio and then television diminished the demand. The family which had owned these books appeared to have bought every novel or Romance which came from the presses. But few readers nowadays desire the forgotten fiction of yesteryear; and usually they are right to disregard it; life is short.

Nearly every volume on the shelves of that peculiar bookshop was priced two dollars—which meant that eventually most of those books were pulped, I suspect; it would have been difficult to move them had their price been ten cents apiece. But on one of those shelves reposed nearly all the fiction of Francis Marion Crawford. Thus I filled some gaps in my collection; what I did not buy eventually was converted into newsprint, I fancy, if not burnt.

So, over nearly half a century, I courted the company of the shade of Marion Crawford. All that I knew of him I had gleaned from his own pages—until the publication of Pilkington’ s life in 1964. Has a fatality linked us? It would be most pleasant to think that Crawford might like my tales so well as I like his; but I do not delude myself; I lay claim only to being, in some degree, his unworthy Romantic disciple.

John. C. Moran performs a pious act in renewing our knowledge of F. Marion Crawford—an act pious in the old Roman sense, so well understood by Crawford himself. Our own literary milieu has grown sick upon a gluttonous vampire-diet of unnatural Naturalism; Romantic convictions and Romantic modes have been relegated to the sub-literary catacombs, and have become scarce even there. Yet, as T. S. Eliot reminded us, there are no lost causes, because there are no gained causes. We seem to be entering upon an age of mystery and trial. Out of renewed perceptions and chastening experiences may come a fresh search for the wondrous. A century after Crawford began to publish, the Romanticism which he eminently represented may begin to assert its power once more. As Robert Frost instructs us, truths are forever going in and out of fashion. To the truths perceived by the Romantic imagination, F. Marion Crawford’s better novels and stories and excursions in history remain handsome approaches which we traverse by owl-light.

© The Russell Kirk Legacy, LLC

Classic Kirk:

Classic Kirk: