By Peter K. Andersson.

Princeton University Press, 2023.

Hardcover, 224 pages, $27.95.

Reviewed by Jesse Russell.

No! I am not Prince Hamlet, nor was meant to be;

Am an attendant lord, one that will do

To swell a progress, start a scene or two,

Advise the prince; no doubt, an easy tool,

Deferential, glad to be of use,

Politic, cautious, and meticulous;

Full of high sentence, but a bit obtuse;

At times, indeed, almost ridiculous—

Almost, at times, the Fool.

— T.S. Eliot’s The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock

Our own strange postmillennial age is one in which comedians have come under great scrutiny for their work and are subjected to strong condemnation for incorrect or offensive political or cultural comments. It is often remarked that in earlier times, a comedy or fool was granted license to tell the truth with boldness—even to the highest political powers. However, the matter is much more complex.

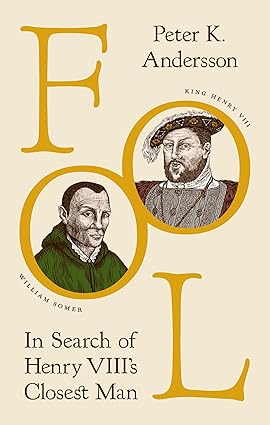

In his recent work, Fool: In Search of Henry VIII’s Closet Man, Örebro University historian Peter K. Andersson provides the narrative of Henry’s fool, Will Somer. One of Andersson’s central points is that beneath the intrigue and political and religious developments of the Tudor period was the presence of one man who spent more time with Henry VIII than any other. Andersson notes the paradox that despite his intimacy with Henry, historians have not paid close attention to Somer’s life. Somer was not only important to Henry; he persisted with the Tudors through the reigns of Edward and Mary and was present at Elizabeth’s 1559 coronation. Drawing from references to Somer in sixteenth and seventeenth-century literature, Andersson argues that Will Somer was one of the most famous people of the Tudor Era. In fact, Somer became known as the archetype of the fool. In the prologue to Shakespeare’s Henry VIII, there is even an apology for Somer’s absence from the play. Andersson argues that Somer is an important figure of study, for he shows how aristocrats interacted with commoners, how people with disabilities were treated in the Renaissance, and how Early Modern people understood comedy. Somer is further an important object of study through Jacob Burckhardt’s notion of the Renaissance as the time of “the development of the individual.”

Even more than the major literary figures of the era, Early Modern fools remain a mystery due to the lack of source materials. Andersson makes the curious point that being hostile toward learning was an essential component of the Renaissance fool’s character. To prove his point, Andersson provides the humorous quote from the literary Will Somer of Thomas Nashe’s Summer’s Last Will and Testament: “I profess myself an open enemy to ink and paper.” As Andersson further notes, in the Early Modern period, there was a distinction between natural and artificial fools. Whether the person had a genuine disability or merely a rough rustic and “country-fied” personality, the fool was chosen, Andersson argues, because of his or her personality’s contrast to the elegance of courtly life. It is unclear whether or not Somer was a natural or artificial fool; there is evidence to point to both possibilities. Moreover, it is possible that Somer was, as Shakespeare’s Hamlet himself, both mad and acting mad—both a (semi-) natural fool as well as someone who constructed the exterior personality of a fool.

There are only a few things that we know about Will Somer. He appears in the court of King Henry VII, in Andersson’s words, “as if out of nowhere.” Andersson provides the interesting historical anecdote that it was possible for exceptionally gifted or outlandish peasant villagers to be recruited by the court. He would play Vice at Christmas festivals (where he would engage in “combat” with another fool and a young King Henry) and was possibly a collector of buttons and seemingly an admirer of green apparel. He was an important symbol or “mascot” (Andersson’s term) for the court of Henry VII and appeared in several portraits: he appears in an illumination from Henry VIII’s psalter as well as Portrait of Henry VIII and His Family (ca1550- 1552) and a Posthumous Portrait of Henry VIII with Queen Mary and Will Somers the Jester (1550s). The presence of Somer in these portraits near the depiction of the king himself, for Andersson, emphasizes Somer’s importance. He was compared to a lazy cat or dog for his alleged sleepiness and languid nature. He may have been beaten or physically disciplined, and he could respond with violence to provocation; this affirms the notion that Early Modern comedy could be cruel. He could rant and rave at various annoyances he had, but he seemed to develop an understanding of the limits of what he could and could not get away with.

Finally, for Andersson, Somer is an important figure in the history of comedy. Andersson notes that Hamlet’s expression of displeasure at fools in general, or at least artificial fools, in his direction to the actors, is a prelude to the contemporary twenty-first-century preference for more subtle humor instead of outrageous and vulgar comedy. Andersson sees this comment from Hamlet as being part of a movement in the Elizabethan period away from the “low” comedy of many clowns. Shakespeare’s earlier clowns are more of the lower type of comedians, whereas the fools of his later works represent more of the half-natural and half-artificial fool that Will Somer allegedly was. Andersson states that what made fools truly funny was their spontaneity and lack of intentionality.

Peter K. Andersson’s Fool is a unique work that probes the life of a largely ignored but important Renaissance figure. Much research since the advent of critical theory and postcolonialism has labored to broaden the historical canon to include marginalized figures. Sometimes these efforts have become excessively politicized and provoked strong reactions. Other times, these efforts have largely relied on speculation that, at times, degrades into fantasy. However, in Fool, Peter K. Andersson provides a well-researched and thorough explanation of a man who only appeared to historians as a marginal figure, but who was a seemingly important member of Henry VIII and his children’s social milieu. Andersson’s work is also an important contribution to the field of disability studies, an important scholarly field that helps to unearth the complexity of human intelligence.

Jesse Russell has written for publications such as Catholic World Report, The Claremont Review of Books Digital, and Front Porch Republic.

Support the University Bookman

The Bookman is provided free of charge and without ads to all readers. Would you please consider supporting the work of the Bookman with a gift of $5? Contributions of any amount are needed and appreciated!