by Mark Dery.

Little, Brown and Company, 2018.

Hardcover, 512 pages, $35.

Reviewed by Eve Tushnet

Many years ago I saw an obituary notice in the local gay newspaper. Above a desolate, elegantly hand-drawn landscape ran the motto: “Last night it did not seem as if today it would be raining.” And then the dates of a loved one’s birth and death.

The picture and the words were from Edward Gorey’s little book, The Sopping Thursday. Gorey is famous now as a master of the macabre, with an oeuvre full of menacing gigantic curtain tassels, “neglected murderesses,” insect gods demanding human sacrifice, and children dying in ridiculous ways. (“N is for Neville, who died of ennui.”) He modeled his drawing style on engravings, and took both form and content from “obsolete genres”: “the Puritan primer, the Dickensian tearjerker, the silent-movie melodrama.” But Gorey was also astonishingly skilled at finding poignancy, lostness, in the most trivial moments of life. He had a fine sense of absurdity, but his nonsense was always shadowed by a feeling of real loss.

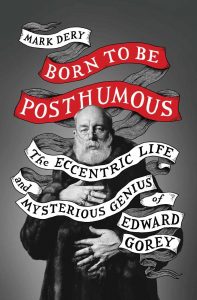

Mark Dery seeks to give Gorey his due in a new biography, Born to Be Posthumous: The Eccentric Life and Mysterious Genius of Edward Gorey. He places Gorey back in his real origins: not an Edwardian but a Midwesterner, a man formed in the 1950s whose women friends have nicknames like “Bunny” and “Skee.” He shows us the five-year-old reading Dracula, the grown man who literally let poison ivy creep into his living room; but also the man with what a college friend called “solid, middle-class values,” who exclaimed things like, “Jeepers!” Dery notes Gorey’s reticence, his diffidence, his “fatalistic way of viewing the human comedy.” He rescues what might get lost under the heap of tributes, of Simpsons parodies and steampunk dance parties—Gorey’s lyrical sense of form, his haunting use of negative space, his spidery lines extending longingly into emptiness. He even honors Gorey’s late-life forays into community theater (“I want to see this clothespin emote”) and the formal experimentations of his late works, including a pop-up book, a “tunnel” book which works somewhat like a Viewfinder, a choose-your-own-adventure book, and more.

At 400-plus pages, the book puts the labor back in “labor of love.” There’s a galumphing quality to this book, and a tendency to overread. Gorey can’t just be influenced by Japanese art; he has to be “Taoist.” He can’t just write nonsense; he has to be “Derridean.” Do we need to turn to Taoism to explain a reclusive cat fancier’s love of animals?

Dery explores, more subtly and cautiously than it first might seem, the possible influence Gorey’s sexuality had on his work. It’s no coincidence that I saw that Gorey-adorned obituary in the gay paper. Virtually all of Gorey’s influences were gay, as were many of his friends. Gorey’s persona was so extreme as to be brazen. He was a balletomane who wore rings on all his fingers, who loved The Golden Girls, who described his World War II basic training as “too, too feeble-making”—who fell in love, with unhappy results ranging from the tempestuous to the insistently thwarted, with men.

Was that enough to make him gay? And does that question matter for his work? Dery chooses not to answer the first question. Gorey spoke dismissively of “sex entanglements” and said, “I’ve never said that I was gay and I’ve never said that I wasn’t. A lot of people would say that I wasn’t because I never do anything about it.” (About what, one might ask.) Gorey was what he called “accident-prone” in love: subject to infatuations, resulting in emotional injury and, in one case, thoughts of suicide. He was a social butterfly (or bat) who learned to keep others at arm’s-length.

It seems maladroit to approach Edward Gorey’s psyche at all—one can imagine an alienist or a medium in the Gorey parlor, but an analyst? And yet Dery suggests, sometimes crudely (Gorey’s one and only abortive “attempt at sex” is his “Rosebud moment, the experience that made him who he was”) but often more incisively, that Gorey’s private, disappointed passions influenced his style.

The most obvious influence is simply that Gorey’s very camp. He’s got that aesthetic approach to life’s little tragedies, that embrace of grotesquerie, that refusal to take death or loneliness seriously—a refusal which calls attention to its own fragility. His ridiculous menacing tassels might serve as an image for his method overall: Take the trivialities of life and blow them up to giant size, making us laugh at our little passions and sufferings, but never forget that we laugh because we recognize our real helplessness in the face of the giant curtain tassels of life. See, for example, this perfect Gorey limerick:

A headstrong young woman in Ealing

Threw her two weeks’ old child at the ceiling;

When quizzed why she did,

She replied, “To be rid

Of a strange, overpowering feeling.”

Great camp relies on poignancy—without it, camp descends into crudeness, as the love of what’s grotesque becomes edged with blame instead of pity. But Gorey’s work has a deeper melancholy than most camp. He portrays a world where communication is impossible, where significant words (“catafalque,” “remorse,” “phylactery”) march across a nursery wall unhooked from any meaning or connection to life. Dery calls his style “an aesthetic of the inscrutable, the ambiguous, the evasive, the oblique, the insinuated, the understated, the unspoken.” Gorey himself meditated frequently on indescribability: “Ideally, if something were good it would be indescribable. What’s the core of Mozart or Balanchine?” That this world was created by a man who himself was a collage of silences and resignations should not be too surprising.

At one point Dery notes that Edward Lear, the Victorian nonsense poet and great influence on Gorey, was himself badly disappointed in love of a man. Gorey said, about children’s nonsense verse, “[T]here’s probably no happy nonsense.” It’s better to live in a nonsense rhyme than in a joke, if you’ve ever been the punchline. Perhaps nonsense—what one Gorey title called “Alms for Oblivion”—is the gentlest response to humiliation in love.

Eve Tushnet is a writer in Washington, DC. She blogs at Patheos.