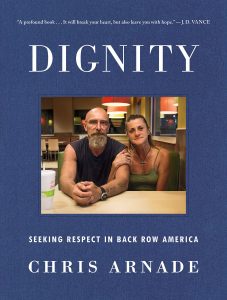

by Chris Arnade.

Sentinel, 2019.

Hardcover, 304 pages, $30.

Reviewed by Addison Del Mastro

It is an understatement to say that Dignity: Seeking Respect in Back Row America, is an important book: it is a must-read. And the fact that it comes out as President Trump’s reelection campaign looms doesn’t hurt.

In fact, while it is decidedly not one of them, Dignity looks at first blush like it might be another “how we got Trump” entry; that familiar genre replete with Midwestern diners and struggling main streets and fed-up fiftysomething men grousing in dive bars. Dignity also resembles British conservative Theodore Dalrymple’s Life at the Bottom, an exploration of the (mostly white) British underclass. But what sets Arnade apart is that he is not a professional journalist or sociologist, peppering analysis or narrative with anecdotes gleaned and selectively chosen from a few quick trips out to Middle America. Anecdotes of Middle America—and the Bronx, and Selma—are almost the entire book.

While Arnade has found favor with conservatives—two of my colleagues at The American Conservative have written about his work, and J. D. Vance of Hillbilly Elegy fame has a blurb on the back—he is himself a classic leftist. The sort, for example, who believes that “political structures are far more responsible for people’s behavior than individual responsibility.” On the other hand, he decries the fact that America’s elite “only care about one form of meaning, which is the economic.” He is firm in his conviction that racism is to blame for much of the black community’s struggles; but he also notes that he has been excommunicated by some on the Left for caring just as much about struggling white people. He eschews technocracy and believes that the problems he observes are simply “too big for any policies.” Arnade is refreshing in his mix of humility and forthrightness.

First, an element that conservatives might not like: Arnade firmly believes in harm reduction when it comes to vices like prostitution and drug addiction. He helps some of his subjects avoid police run-ins, and at one point finds a drug user a place to shoot up safely. He passes little or no moral judgment on these habits and lifestyles. To a cynic or a traditionalist, this can all look like enabling antisocial behavior by seeking to reduce its costs. One can also imagine the argument being leveled, at least regarding the people of color he meets, that Arnade is the “real racist,” betraying the bigotry of low expectations by eschewing personal responsibility and individual agency.

But none of this would be accurate, let alone charitable. Arnade explains that his support for harm reduction comes from humility: from observing that in far too many cases what cops or social program managers think is best for transient or struggling people simply does not work. He does not presume to know what will work, but perhaps it is cruel to make life as difficult as possible for such people, especially when little is being done to remedy the conditions that shaped their suboptimal choices.

If the reader can accept this approach to social problems, then the rest of the book is likely to be easy reading, though not pleasant. The core theme of Dignity is that America is increasingly divided into two classes and worldviews, which Arnade dubs “front row” and “back row.” To simplify only a little, in the front row are rootless elites who rush out of their hometowns, pile up degrees, and chase high-paying or high-prestige jobs. Most of the people in the higher reaches of journalism, government, business, and academia fall into this category. “Back row” America includes the people who couldn’t, or didn’t want to, leave their hometowns; who value non-material and non-economic things like family, place, home, and faith.

Like all categories, these are much neater than the real world, but they capture a core truth: the elite do not fully understand why people would choose a lifestyle different than their own, and often are not fully aware of the systemic barriers to doing so. The resulting policies and worldviews they propagate are not necessarily malicious, but they are often ignorant and counterproductive. Despite imagining themselves as individualistic and free-thinking, the front row tends to do what Arnade himself did before he left his plum job as a Wall Street trader: “I had removed myself from the realities of the majority of Americans.”

But for all the opportunities Dignity offers to consider policy and economics, or to cast shade at the elite, this is almost all subtext. The book is centered on the people and communities Arnade meets, whether in various McDonalds or deserted main streets or disfavored urban neighborhoods or Wal-Mart parking lots off interstate ramps. Arnade’s America, largely invisible to the elites, is an unrelentingly grim one. It is an America ravaged by decades of drug addiction, drug war, urban crime, racism, white flight, and deindustrialization. Arnade demonstrates something familiar to watchers of the 2016 election: America is divided by class and race to be sure, but it is also divided, perhaps even more decisively, by geography.

One realizes, particularly when reading the interviews with older African Americans, how recently in our history grinding poverty was the norm, and how short our time as a more-or-less universally affluent country has been. Arnade himself remembers shotgun houses without running water, and plenty of his interviewees do too. One also realizes, or is reminded, that many African Americans have never enjoyed a standard of living befitting a developed country.

After seeing Arnade’s photos, included between chapters, and reading story after story of decline and disintegration—a homeless dad pushing dirty kids aimlessly around in a shopping cart; more ruined downtowns than you can count, some miles and miles from the nearest schlocky chain store; mass graves for dead homeless off Long Island—one wonders whether the United States really is a developed country. Many social scientists no longer think so. In fact, one at times even struggles to believe everything Arnade recounts, though there is no reason to disbelieve him other than what not doing so would do to your own sense of virtue and patriotism. Perhaps the most charitable explanation for why the elites ignore the plight of the “back row” is that they cannot imagine that any of this actually happens in America.

In perhaps the most unsettling vignette, Arnade learns about one of the only jobs available in Selma: scraping the mortar off old bricks, salvaged from demolished warehouses that once, perhaps, provided somewhat better jobs. The work pays poorly, is very hard, and not infrequently results in injury. The work exists because salvaged bricks are worth a lot of money for their “historical charm.” “Most of the buyers,” Arnade explains, “are fancy restaurants in fancy neighborhoods, places where Selma seems so far away.”

There are other interesting bits that underscore how independent people are, and how they resist easy categorization. There are African Americans who decry racism, rap, and black-on-black crime all at once. There are Somalis who prefer white neighborhoods to black ones, because they feel they are not welcomed as “really” black. There is a transgender woman, a prostitute, and many drug addicts who believe strongly in God and Jesus. There are charming, chaotic street scenes in which a kind of order and equilibrium somehow establishes itself.

Arnade has few policy recommendations, though he pointedly condemns an economic system that “requires everyone to always be economic migrants.” He makes few moral judgments, preferring to view human behavior, at least at the macro level, as arising out of certain contexts and conditions. His conclusion—that we should listen to each other and open our eyes—will strike some readers as anticlimactic. But perhaps there is no other answer.

How easy would it be for the average person to go, Arnade-style, to disfavored neighborhoods and learn about “back row” America? “Nothing negative ever happened,” Arnade says: no muggings, no stabbings. Even in the “worst” places, the vast majority of people are basically decent. Arnade suggests spending some time in a poor or majority-minority neighborhood (too often the same thing) near you. Some people, ensconced, perhaps, in exurban superzips, will bristle at this. It’s okay to bristle, because it means you’re listening.

Addison Del Mastro is assistant editor of The American Conservative. He tweets at @ad_mastro.