By Grace Hamman.

Zondervan Academic, 2025.

Hardcover, 224 pages, $29.99.

Reviewed by Nadya Williams.

A few years ago, my husband and I learned we were expecting a girl. As we were considering possible names, we loved the sound of many of the virtue names that were so popular with the Puritans—Chastity, Prudence, Temperance. Just imagine Prudence Williams! Doesn’t this sound like a good Puritan name? But we were also prudent ourselves in this process, or maybe just realistic: no way could we name our daughter one of those names in this day and age. Virtues like prudence have become more a subject of mockery than something to respect and admire. At the end, we settled on Mercy—a rare virtue that is still greatly admired today.

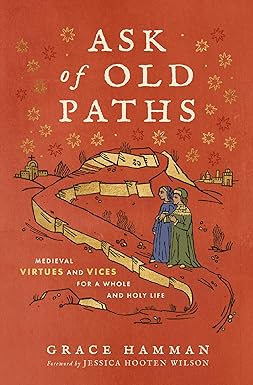

I was reminded of this decision process while reading Grace Hamman’s beautiful (in every way!) new book on the virtues as they appear in Medieval art, literature, and imagination—Ask of Old Paths: Medieval Virtues and Vices for a Whole and Holy Life. Our language of the virtues is stunted, Hamman rightly bemoans. This is because the modern conception of the virtues is remarkably impoverished. Not only are the virtues not popular in secular culture, in which such virtues as chastity seem decidedly silly, but even in our churches, the virtues sound more like moralistic killjoys than something beautiful. And yet, Christians in the past recognized something important: “The virtues are one helpful way the historical church thought about spiritual transformation and growth, of the fruits of the Holy Spirit and the life of love.” And so, instead of considering how we might fulfill a list of rules, thinking about the virtues invites us to answer a much deeper, more powerful question: “Wilt thou be made whole?”

What does it mean to be made whole in a world that is deeply broken and where we are constantly reminded of that brokenness in nature, in the actions of other people towards us, and worst of all, in our own actions towards others? This begins with a humbling awareness not only of the virtues that we may realize we lack but also of vices in which, alas, we may abound. And so, Hamman pairs in each chapter a vice and a virtue that counteracts it along with beautiful and sometimes unexpected (to our modern imagination) images of these virtues and vices in Medieval literature and art. So we find pride coupled with its antidote of humility, envy and love, wrath and meekness, sloth and fortitude, avarice and mercy, gluttony and abstinence, lust and chastity.

The striking imagery is what sets this book apart. The Medieval world is different from ours in its imagination. For instance, one image that recurs is of the soul as a garden, lush and blooming when filled with virtues, but also prone to damage by the vices lurking near, eager to sneak inside: “as the fourteenth-century pastoral work The Book of Vices and Virtues describes, into this holy verdancy slithers envy, a basilisk who seeks to ‘restrain’ this lush abundance. An enormous serpent with a crest, or a cock with a snake’s tail, the basilisk kills with one glance. It is so overwhelmingly venomous that its breath scorches the earth… The basilisk of envy desires another’s holy green to crackle and stiffen in death.”

It all sounds theoretical and strange and, in fact, overly poetical (and thus, maybe, not practically applicable), until we consider the all-too-real basilisk that we allow into our own soul-garden whenever we envy someone else. So how might we resist it? How might we drive out this serpent, who is so alive and well today? In response, we consider a devotional picture from c. 1500, Christ’s Heart on the Cross. In this striking image of Jesus on the cross, a large heart is painted to cover his entire torso. Within it is the infant Christ and a nun—the artist herself. Such is the answer to the challenge of envy: It is Christ’s love on the cross for all of us that kills the basilisk of envy and that can heal the corrupted soul-garden within each of us. “Only by clinging to this preexisting reality can we enlarge our hearts and love one another in the fullness of the love of Jesus. Your beloved is already loved; your enemy is already loved. You are already loved.”

Elsewhere in the book, we consider the imagery of wrath, an unrestrained and sinful anger: “In the late Middle English poem The Assembly of Gods, Wrath rides astride a wild boar, bearing a ‘blody, nakyd sword.’ The unsheathed blade reminds us of the perpetual readiness for violence that characterizes the vice of wrath.” We may not see or use swords regularly today, but violence in our society—in word, deed, and thought—is endemic. A striking Medieval image of meekness responds to such horrible violence: The roses from the Cross are able to physically defeat wrath, beating it “black and blue.” Is this meekness? Perhaps not in our modern imagination, but it is one way to envision Christ’s meekness specifically. He is gentle and meek, yet it was with his meekness on the Cross that he defeated sin and death. And, yet again, the roses point us to the garden—the garden of the soul and also the Garden of Eden, where everything was perfect, before humanity fell, before the roses needed thorns to beat up wrath.

Such imagery makes sense when explained yet seems strange at first glance. We do not talk like this. We do not think like this. This is, yet again, our impoverished imagination, existing in blurry black and white, flailing to comprehend a rich world abounding in kaleidoscopic color. Indeed, even in considering images familiar to us, an unfamiliar lesson emerges. So it is that in counteracting the vice of avarice, we meet olive oil (yes, that stuff I just used to roast broccoli for dinner) as an instrument of mercy via John Mirk, a fifteenth-century cleric. “Christ’s body is like an olive tree, he says. Just as an olive tree yields olives and from them olive oil, Christ freely offers mercy, his flowing blood, from his wounded body.”

Through images like these, vices and virtues alike become real, three-dimensional characters in Hamman’s book, and so does the world of Medieval theological thought. Practical theology is not just the stuff of modern books, but was clearly a concern for Medieval pastors, nuns, and creative artists. But there is greater significance here than just our individual edification, important though it is. Yes, our individual character is on the line as we practice virtues and vices. We are formed by our thoughts, our practices, our desires. But something even more serious, truly civilizational in scope is on the line, Hamman realized while writing this book: “Another mistake I had made about the virtues was thinking about them as individual, as belonging to individuals and being individual in themselves. But we are communal creatures, social animals by our nature. The very development and practice of virtue is a collective labor of beauty and struggle.”

We live in a world thirsty for beauty and goodness and truth. Perhaps it was always this way, and perhaps denizens of every other age felt like it was all just on the verge of slipping away. Whether this is just the normal weight of human life or not, it does feel heavy. But Christ’s call to follow him and to become more like him through the practice of the virtues extends to us all still.

Nadya Williams is interim director of the MFA in Creative Writing at Ashland University. She is books editor at Mere Orthodoxy and the author of Cultural Christians in the Early Church (Zondervan Academic, 2023), Mothers, Children, and the Body Politic (IVP Academic, 2024), and the forthcoming Christians Reading Classics (Zondervan Academic, November 2025).

Support the University Bookman

The Bookman is provided free of charge and without ads to all readers. Would you please consider supporting the work of the Bookman with a gift of $5? Contributions of any amount are needed and appreciated!