edited by Matthew McGowan and Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis.

Empire State Editions, 2018.

Hardcover, 304 pages, $35.

Reviewed by John Byron Kuhner

Among the memories of my New York City childhood—graffiti everywhere, endless games of off-the-wall, big cookies with colored sprinkles, getting beaten up by a kid named Alvaro—is the day I really saw classical architecture for the first time. We were on a third grade trip to the Museum of the American Indian. It was a drizzly, glum November morning. Our bus pulled up in front of the museum, and through the schoolbus window I peered out at the tableau: drops of rain on the window, beat-up cars scattered along the street, and between the empty gray sidewalk and the cloudy gray sky was a worn gray building, silent and monumental, a long line of columns stretching all the way down the block. The near columns seemed to gaze down at me like giants; the distant ones waited quietly for me to approach. They were a presence—beings with personal force, something far greater and older than the commoner stuff of a city. The memory was so strong that when I visited the same collection two decades later, I could tell at a glance that the columns you see on the outside of that institution today were not the ones I saw as a child. And my memory was correct: the museum had moved in the meantime, from Audubon Terrace on 155th Street, to the Customs House downtown. Both are monumental beaux-arts structures with grand colonnades, but I could tell them apart at a glance at a distance of two decades.

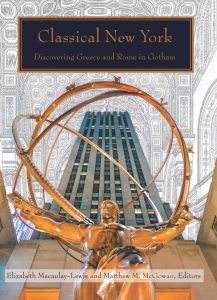

This kind of encounter with the Classical is part of what it means to live in a great cultural capital—part of the plus side of the urban ledger book, to counterbalance the cost, the congestion, the crime, the discomforts, and all the rest—and as it implies a kind of conversation between past and present, it remains an endlessly interesting topic. And so I was pleased to find my copy of Classical New York: Discovering Greece and Rome in Gotham in the mail, and I read it through over the course of a pleasant week.

The book is not a guidebook and not comprehensive—though what a lovely project that would be—but instead a collection of nine scholarly essays providing relatively in-depth treatment of select topics. Some are as obvious and familiar as they are indispensable in such a collection: the architectural essays on Federal Hall (by New York City living cultural treasure, Francis Morrone) and old Penn Station (by Maryl B. Gensheimer). Reading about Penn Station, and seeing those pictures again, is enough to make any New Yorker weep, but I found some consolations in Gensheimer’s account: much of the architectural stonework, which looks so impressive in photos, was actually fake!

The waiting room presented the viewer with a material illusion—and allusion to ancient Rome—that was ingeniously wrought. The plaster of the ceiling coffers, for instance, was dyed slightly so that its color would match the travertine veneer of the walls. And, in fact, much of what appeared to be travertine was not actually travertine. Even while promotional literature proudly advertised the fact that Pennsylvania Station was the first building in America to use travertine from the same quarries used in Roman antiquity, that travertine was used quite sparingly for pilaster bases and low-lying trim—in other words, those areas of the waiting room at, or just above, eye level with travelers. McKim, Mead, & White created a formula for synthetic stone that was mixed by the workers on site for the upper zones of the walls.

Even those magnificent seven-foot diameter columns were hollow! “Thin veneers of travertine were wrapped around and pinned to an interior steel support.” One of the photos shows the papier-mache-like work on the ceiling: it looks like the sort of videri quam esse work that Hollywood is so good at, and indeed it might be one of the most characteristic American styles: the Faux. When I was in Milwaukee not long ago, I saw a crew repairing a damaged cornice on a Beaux-Arts federal building. The removed portion was being replaced with a ten-foot-by-six-foot block of styrofoam painted to look like granite. I was tempted to lament our fallen age, but who knows? Perhaps the original was not real stone either. Granite generally doesn’t break. But it’s hard to tell from a hundred feet below.

Architecture is but one element of the Classical tradition in New York, and one of the things that makes this collection so readable is its variety. A particularly fine essay by Elizabeth Bartman, “Archaeology versus Aesthetics: the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Classical Collection in Its Early Years,” describes the principles and difficulties involved in creating a Greco-Roman collection to satisfy the young metropolis’s ambitions. Archaeological digs could produce scientifically interesting material, but chances are always slim that a dig will reveal a masterpiece of world-historical significance. And such masterpieces are almost never available for sale either—the Elgin Marbles are not likely to show up at Sotheby’s anytime soon. Bartman traces how various curators attempted through connoisseurship to acquire pieces that were especially beautiful as objects, rather than, say, collections of military equipment or ancient furniture, resulting in

the present collection, a museological triumph thanks to its many exquisite works. At the same time, the focus on masterpieces has created the collection’s fundamental shortcoming: a dearth of contextual information that would enable viewers and scholars alike to understand more fully what they are admiring.

A trip through the galleries with Bartman will make you see the collection afresh—as the result of decades of choice and selection and rejection.

Another eye-opening essay, by Allyson McDavid, traces the history of public baths in New York (“The Roman Bath in New York”). This was a part of city life about which I knew nothing, other than a childhood memory of city bathhouses getting shut down to stop the spread of AIDS. She provides a list of no fewer than forty-seven such public bath complexes in the city—they were clearly far more important than I had ever imagined. At the same time, McDavid does a fine job describing how these baths differed from Roman ones, an example of the double-vision in time these classical references provoke: many of these essays illuminate not only New York culture but also its Greek and Roman antecedents. It’s a particularly rewarding, culturally deep way to interpret the city.

Despite the diversity of essay materials, and despite the fact that the book’s depth means it cannot comprehend the breadth of the city’s Classical treasures, several threads help bind the book together: it feels like a single united effort. The architectural firm of McKim, Mead, & White is one such thread; the “White City” at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago is another. This exposition, and the classicizing ethos that produced it, is described in depth in Margaret Malamud’s “The Imperial Metropolis.” The “White City”—another American Faux, made of temporary materials and taken down afterwards—was, according to one observer, “the finest architectural view that has ever been beheld on our planet.” Looking at pictures, I won’t deny the claim, but we are still waiting for someone to actually build it in stone and steel. Jon Ritter’s article about the “City Beautiful” movement, and New York’s Civic Center just north of the Brooklyn Bridge, describes the municipal efforts to build such a “White City.” Particularly intriguing are the arguments theorists, such as John Brisben Walker, editor of The Cosmopolitan, brought for Classicism against laissez-faire, capitalistic urban development:

One represents human effort disastrously expended under individual guidance in the competitive system which takes no thought of neighbor. The other represents organization intended for the best enjoyment of all. One stands for the remnant of barbarism handed down through the centuries. The other stands for the aspiration of the human mind under the unfolding intelligence of an advancing civilization.

Yet in the very next chapter, Jared A. Simard discusses the personal vision and involvement of a single capitalist, John D. Rockefeller, and his intentions when he decorated Rockefeller Center, his “city within a city,” curiously, with statues of Prometheus and Atlas.

One of the real discoveries of the book is the in-depth, fascinating essay by Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis (one of the book’s co-editors), about the Gould Memorial library in the Bronx, Stanford White’s summum opus, “New York’s greatest forgotten architectural masterpiece.” I certainly knew nothing about it, and I’ve lived in New York my whole life and have a mother from the Bronx to boot. Macaulay-Lewis describes the building, a rotunda based on the Pantheon, and compares it to other Pantheonic structures, including the Low Library at Columbia, built contemporaneously. The fate of the library is no small part of the intrigue of the article: once part of NYU’s Bronx campus (another revelation to me), it was sold off to the Bronx Community College. One of the building’s oculi—the central windows in the dome letting in light—was destroyed by a molotov cocktail in 1968. Another was simply closed off, the natural light replaced by “gym lights.” Even thus degraded, this seems like a place New Yorkers need to visit.

The collection ends with a tour of New York City’s classical inscriptions, from Latin epitaphs in the old cemeteries to the Vergil quotation at the National September 11th Memorial. This delightful essay by Matthew McGowan, the book’s other co-editor, contains a literary version of this temporal double-vision, with Seneca, Tacitus, Oliver Goldsmith, and Samuel Johnson appearing on the streets of New York, in the form of learned inscriptions. There is also some truly enjoyable drollery about the teapot tempest created when Professor Andrew West, Dean of Princeton University’s Graduate School, decided to render “New York Academy of Medicine” into Latin as “Academia Medicinae Nova Eboracensis”—and have it inscribed in massive stone letters on the building’s facade. Dr. William Francis, librarian at McGill University, wrote (correctly) to the Academy’s president, “your professor’s ACADEMIA MEDICINAE NOVA EBORACENSIS can only mean ‘the new academy of medicine at York’ or, on his own theory, ‘the new academy of York medicine.… with all due tact and respect, drop the Princeton professor and consult the Latin secretary of the Cardinal Archbishop of New York.” Dr. Frank Gardner Moore, professor of Classics at Columbia, took up the cause again five years later, complaining that the inscription is “an error, which in such stately lettering is literally monumental!” The controversy continued for years more, when the next president of the Academy wrote, “With the finances of the Academy of Medicine what they are, I guess we’ll leave the inscription as it is, inasmuch as the estimated cost of the change would be $653.” Later, an academy trustee, Dr. Frissell, contributed his own excuse to the decades-long debate: “we trusted that the inexpertness of the average New Yorker in Latin might cover up the deplorable ignorance of the inscription.”

As McGowan notes, “Dr. Frissell and the Academy trustees blithely miscalculated. Average New Yorkers continue to notice the inscription’s ignorance.” Or at least un-average New Yorkers do. And those un-average New Yorkers wishing to read their own city better, and discover the Greece and Rome that is in New York, should treat their New York bookshelves to a copy of this unique volume, and beg the editors for more.

John Byron Kuhner is the editor of In Medias Res, the Paideia Institute’s online magazine, and former president of SALVI, the North American Institute of Living Latin Studies.