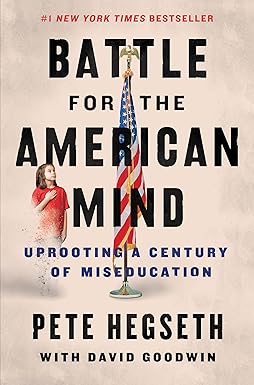

By Pete Hegseth and David Goodwin.

Broadside, 2022.

Hardcover, 288 pages, $32.

Reviewed by John Kainer.

Friedrich Nietzsche is perhaps most famous for the words he has a madman speak in his book, The Gay Science. The madman, standing in the midst of unbelievers, cries out,

God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him. How shall we, murderers of all murderers, console ourselves? That which was the holiest and mightiest of all that the world has yet possessed has bled to death under our knives. Who will wipe this blood off us? With what water could we purify ourselves? What festivals of atonement, what sacred games shall we need to invent?

What is less well-known is that, in the next paragraph, the madman goes quiet, his captivated audience stunned into silence. “I have come too early,” he mutters, adding that “my time has not come yet. The tremendous event is still on its way, still travelling— it has not yet reached the ears of men.”

Nietzsche meant for us to contemplate how Christianity propped up and supported our ideas about morality and how, with God being dead, the inherited moral system, and all of its offshoots, were now without the necessary support to sustain itself. Nietzsche recognized that this problem was far more than a philosophical issue; it was a profoundly cultural one as well. Our English word culture comes from the Latin cultus, meaning “care,” and the Latin cultura, which means “to cultivate.” Thus, a cultural issue is one that upends the system in which people were cultivated. This is, in one sentence, what Battle for the American Mind is all about.

This book hinges on the idea of paideia, which is roughly defined as that which is “made up of ideas, presumptions, beliefs, affection and ways of understanding that define us.” Authors Pete Hegseth, current Secretary of War, and David Goodwin point out that this paideia is not just some random product of evolution, but something that can be actively cultivated. In short, a paideia shows people what a good life is and what virtues are needed if one is to live a good life. Culture, then, is downstream of paideia the same way politics is downstream of culture.

The central thesis of the book is that the Western Christian paideia that made the American experiment in liberty and self-government possible has nearly been stamped out of the public schools. Hegseth and Goodwin assert that this paideia was gradually replaced by a progressive paideia (referring to the early 20th-century movement) and has been recently replaced by a Marxist paideia focused on issues like equity, diversity, and social justice. This paideia is inculcated in students from the time they start kindergarten, reinforced in higher education and corporate America, and is taught in the schools of education at universities. School boards, overwhelmingly formed by this Marxist paideia, ignore the criticisms and concerns of parents regarding both the curriculum and the style of teaching used in their children’s classrooms. Finally, the public-school teacher’s union acts to protect this paideia, this style of pedagogy, and this curriculum through political means.

The book is organized into three parts: the 16,000-hour rule, the Unauthorized History of American Education, and a Solution as Big as the Problem. The first part is concerned with demonstrating how conservatives have focused on the wrong end of the educational system—higher education—while the real damage is done during the mandatory 16,000 hours that comprise a public-school education from kindergarten through the twelfth grade. Fostering virtue in children requires both instruction and practice, and, as Hegseth and Goodwin demonstrate, one hour of church and one hour of religious education on Sunday is not sufficient time to counter approximately forty hours of instruction per week rooted in the secular paideia. Laid out in this way, the problem of the American education system looks much different, and the battle over school choice and educational vouchers takes on a whole new meaning. The best part of this section occurs towards the end when Hegseth and Goodwin compare the Western Christian paideia’s approach to education to the progressive paideia’s approach to education. Perhaps the most striking juxtaposition concerns the approach to history, where the WCP endorses studying classics and history, the APP contends that the newest ideas are the only ones worth knowing.

In the second section of the book, “The Unauthorized History of American Education,” Hegseth and Goodwin demonstrate how the progressive movement paved the way for critical theory and Marxism to enter American public-school classrooms. How did this happen? All talk of transcendence and virtue was wasted, but it could not simply be removed from the curriculum. Instead, it must be replaced. The Progressives framed the classical education of former generations as something unfit for the masses who would work in occupations focused on manual labor. In addition, the progressives emphasized a nationalistic and democratic message in the public school system with the goal of producing graduates steeped in “democratic values” and who thought of themselves as belonging, above all, to their nation. This dovetailed with the progressive view of democratic government as something to be actively used, a weapon to be wielded in the battle against injustice. Once the transcendent standards of God were replaced by the standards of the progressives, the very idea of education as something more than a social construction became unthinkable. Into the void opened by the progressives stepped the critical theorists and the cultural Marxists. The way out of this situation is the subject of the final section.

In the final section of the book, Hegseth and Goodwin distill classical Christian education down to four key elements: reason, virtue, wonder, and beauty. The first two chapters in this section are concerned with redefining these terms within the Western Christian paideia. The differences seem subtle at first, but as Hegseth and Goodwin demonstrate with their exposition of what classical education looks like in practice, the differences become very stark. The focus on history, on the interrelation between subjects, on reading great books and great stories, and on challenging students differentiates such schools from their public counterparts. Can all of American education aspire to such lofty and liberating standards? Hegseth and Goodwin cite multiple authors who believe that it is not only possible but would vastly improve the American education system. The final chapters address how the classical Christian school model can become the dominant model in American education. Hegseth, a former senior counterinsurgency expert in Afghanistan, advocates using an insurgency strategy like the one used by Chairman Mao to spark the Cultural Revolution in China. In other words, Hegseth and Goodwin establish a plan to undermine the power and legitimacy of the cultural Marxist educational establishment and replace it with the classical Christian model anchored by the Western Christian paideia.

These chapters, more than any other, represent a break from the usual analysis that one sees on the American right and, to this sociologist’s mind, represent a shift in the thinking of conservatives. No longer focused on playing defense to conserve the inheritance of the last 100+ years, these authors seek to challenge the progressive and culturally Marxist educational establishment. Prior to this, conservatives seemed interested in knowing the ideas of left-wing radicals to guard against them. Hegseth and Goodwin take a decisive step away from that approach, advocating that conservatives employ the ideas of left-wing radicals like Saul Alinsky and Chairman Mao to bring about their own cultural and political goals. I am interested to see if Battle for the American Mind is the vanguard for a new conservatism in education or just a lost regiment that happened to make contact with the enemy.

All things considered, Battle for the American Mind makes a compelling argument, but the evidence offered by the authors will ultimately not be enough to convince anyone who doesn’t already believe that Christian principles should organize our public and private lives. For example, marshalling several quotes from Frankfurt School members Horkheimer and Adorno is not enough for the average reader to understand their hero status on the New Left, their scathing critiques of American culture, and the concerted steps they took to undermine it from within. To address this, one would need to double the length of the book so there are more data points at each of the time periods studied. Those who are unhappy with the state of American education will learn much from the sections on the history of American education and its reform at the hands of the progressives. That being said, Hegseth and Goodwin’s solutions are likely too radical for people who aren’t already sending their kids to private Christian schools or enrolling them in Christian homeschooling co-ops.

John Kainer is Department Chair and Associate Professor of Sociology at the University of the Incarnate Word in San Antonio, TX.

Support the University Bookman

The Bookman is provided free of charge and without ads to all readers. Would you please consider supporting the work of the Bookman with a gift of $5? Contributions of any amount are needed and appreciated!