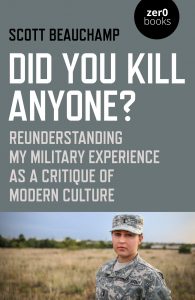

by Scott Beauchamp

Zero Books, 2020.

Paperback, 144 pages, $17.

Reviewed by Anthony M. Barr

The first time I considered enlisting in the U.S. Navy, I was eighteen years old, recently graduated, even more recently unemployed. I had started earning college credits in high school, had racked up quite a number, was planning on finishing out a degree online, and then suffered a bout of debilitating, mind-numbing depression. Amid all my disillusionment, the Navy promised a job, but more importantly, it promised purpose, order, meaning. (I ended up finding a lot of that meaning through the liberal arts education I received at a Great Books college.)

“Why did I join the Army? I didn’t know how to answer the question,” writes Scott Beauchamp, “at least not the way they were asking it in Brooklyn.” I imagine this is roughly equivalent to the incomprehension when a friend tells you they want to become a cloistered monk. Why on earth would you join an order … receive orders … live an ordered and orderly life? In Brooklyn, Scott notes, “it makes sense in the tribe to go to grad school. To spend most of the waking hours of the rest of your life in a classroom. To volunteer overseas for a secular NGO. To not work at all and spend your parents’ money instead.” In Brooklyn, and especially when you’re both an urbanite and an Aspiring Writer, the life script says “to retire when you’re 25. To write and publish your memoirs when you’re 19. To be too busy meditating and skateboarding to work. To be too busy working at a bookstore to meditate or skateboard. To professionally promote parties. To take workshops about how to grow up. To do anything other than serve in the military.”

Why would you enlist? Maybe you enlist because the military offers you ritual, ceremony, identity: you can be “freed from irony and suffused with purpose.” You enlist because consumer culture creates men without chests (to borrow from C. S. Lewis) and yet you are discontent because you grew up with stories of noble men and women and you desperately and deeply desire to live a noble life. Scott writes that “when a young person tells you they enlisted for adventure, what they really mean is that they went on a quest for meaning—our popular vocabulary being too anemic to support the weight of a desire simultaneously so necessary and recondite.” And that’s the rub: in our ironic, consumer-driven, relativistic culture, “we don’t have the words to describe our hunger. We struggle to articulate both the depth of our appetite and what might be required to sate it.”

Our anemic culture, our impoverished language, our meaningless patterns of consuming Doritos and porn are dangerously insufficient, and propel our youth to other sources of meaning—good and bad. You may find meaning in the rituals of field patrol or genuflection at Mass, but you may also find it dressed in white at a rally with a tiki torch in hand. You may find meaning marching alongside your comrades with your gun on your shoulder or as an exorcist-priest at war with the demonic powers of our age, or you may find it by opening fire at a Walmart with an AK-47 you stole from your uncle. But if you think that we can fill the void of meaning with Oscar parties and John Oliver segments, you’re fooling yourself.

The military is a path toward meaning, and a pretty good one. But unlike priestly vows, which are permanent, many who experience the meaning of military service will eventually become civilians again. We should already be able to anticipate the question and its answer. Why are our veterans so depressed? Scott writes: “In civilian life you’re made to sort through all the war experiences that people tell you are responsible for your dissatisfaction. You’re told that it was the war itself which wrecked you and not your return to the commodified world, shallow and brutal as it is.” These men and women discovered their chests, they discovered the dignity and nobility of serving a purpose beyond themselves, and then they come back … to what, exactly? Doritos and porn? Scott writes: “I spent a lot of time on rooftops in Brooklyn after the war. People would gather there to have parties, cookouts, or smoke cigarettes in the sun. Sometimes I would stand at a corner of the roof and imagine I was back on a guard tower, scanning my sectors of fire. In the desert I had found purpose behind the boredom. In the city I found a frenetic emptiness.”

Scott’s book is a much-needed critique, and of course critique is always easier than construction. But I think stepping back to consider Scott’s book as an exercise in cultivating meaning might point the way forward for us. In the beginning of the book, Scott writes that “at root, this is my attempt to make sense of myself. To give my experiences form and logical coherence.” This sentiment has echoes of Augustine, confessing to God as an exercise in receiving selfhood through a unified narrative. I’m reminded of an insight from Rowan Williams, the former archbishop of Canterbury: “A human life is given its unity and intelligibility from outside: when God pulls taut the slack thread of desire, binding it to himself, the muddled and painful litter of experience is gathered together and given direction.” Of course, not everyone will turn to religion for meaning, but I think there’s a principle here, namely that the richest sources of self-identity emerge from the self in relation to people, places, and purposes outside the narrow contours of our own self-will and selfish desire.

The second time I considered enlisting in the U.S. Navy, I was sitting in a seminar room in DC, studying grand strategy, political theory, foreign policy alongside some of the foremost instructors and top students in the nation. Earlier in the summer, Senator Tom Cotton told us to ditch Goldman Sachs and to actually do something that serves our country. And again, I found myself wondering about my life’s calling, and desiring some kind of normative script to provide me with an anchor. This school year, I’ll be an assistant teacher in a classical school, hopefully helping to mediate my students’ encounter with a tradition that predates them (and me!) and that offers them sources of meaning with greater depth than anything churned out by the capitalist machine. Overseeing an energetic bunch of elementary kids at recess is a far cry from talking to Henry Kissinger on the phone with my summer class (!), and yet, if the Beauchamp thesis holds, I think the latter experience will pale in comparison. At least this is the story I’m telling myself, given the kind of self I desire to become. And if not the Navy, there’s always the Reserves.

Anthony M. Barr has been a student in the Templeton Honors College. He writes for Ethika Politika and Circe Institute and has done research on political theory, education policy, and civic and moral virtue for various nonprofits, businesses, and independent publishing companies