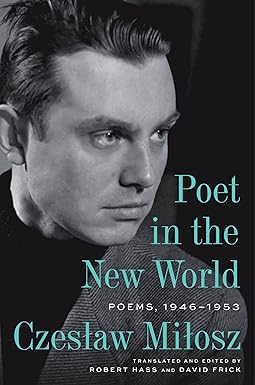

Czeslaw Milosz.

Ecco, 2025.

Hardcover, 160 pages, $28.

Reviewed by Daniel James Sundahl.

When Czeslaw Milosz was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1980, he was introduced as a writer “who with uncompromising clearsightedness voices man’s exposed condition in a world of severe conflicts.” As it is, he’s a poet of history whose warnings about despots carry a terrible weight, as in the poem “You Who Wronged”: “Do not feel safe. The poet remembers. / You can kill one, but another is born.” Here is a man who, from his exile, remembers his European homeland, his Poland, as a place of Gothic cathedrals, of Baroque churches and, yes, “synagogues filled with the wailing of a wronged people.”

The word for this is “sardonic,” which suggests criticism but is neither self-mocking nor deriding so much as colored by a lacerating anger. If I may quote a favorite from “Treatise on Morals,” where the poet comments on books and his opinion is added as a footnote:

I am of the opinion that, however,

That there could be persecutions . . . .

I see a crowd of lady existentialists

Naked, each quivering like a leaf . . . .

Scoffed at and lashed with switches.

And being given in spite of civil liberties,

Fifty-five years hard labor.

I don’t know whether Sartre’s old book

Was worth such punishment

And although this is a joke, the thing is possible.

This is what happens to existentialists.

Or this piece of sardonic wisdom:

Beware madmen. They are nice enough

As long as they are confined to institutions

Or kept in an ordinary stable.

What are they then, these sardonic poems, other than a brilliant mind finding his way in the wake of a catastrophic war and a world coming into being riven by conflicting ideologies?

A personal note, if I may.

I was teaching an Honors English course many years ago. I’m guessing the fall of 1987, which would mark the time as seven years after Milosz’s Nobel Prize and one year after the death of his wife, Janina. I had some choice in reading material and decided to teach Milosz, including his The Captive Mind, Selected Poems, and bits and pieces of biographical material for context. As it was, some money had become available for a Visiting Writers Program. I found what I believed was an agent and phoned to offer a three-day residency. A couple of days later, early evening, my home phone rang. Milosz was calling, likely the first and last time a Nobel Laureate would call me at my home. I’m pleased I answered the phone; I often don’t. He had researched my college and agreed to arrive and give a lecture and a reading, and so we set a time frame and went about travel arrangements, housing, and an agreeable schedule.

The day arrived and I was in the Honors English class; the door opened and in walked Milosz. He had arrived early and had wandered to the bookstore to find his books being taught. If I recall properly, he also came with his friend and colleague Robert Hass. The students, all American students with little knowledge of Polish history, took some time to register that here was this man who had written these two books. His face was worn. And it began to dawn on those students that here was not an accident of history but a phenomenon of history.

After his lecture and reading, the college held a reception at Broad Lawn, our college president’s home. It was well-attended, but I could tell Milosz was uncomfortable. I found him standing by the piano, a concert grand, polished to perfection, and it may have held his reflection. He was softly rubbing his hand across the varnished surface. Lost in thought, this poet of history, of tragic consciousness grappling with reality, this European child of history condemned by such leftists as Neruda for denouncing intellectual acquiescence to all forms of totalitarianism.

I wandered over to thank him for coming. He apologized for being so self-consciously solitary but explained he was in mourning for the loss of his wife. It was not only a personal loss, but a loss of cultural connections, someone with whom he could daily speak Polish and enjoy with her shared cultural nuances, affirming the value of human life and thus a shared life in California, a place far removed in distance and temperament from the scenes of their earlier life.

“In Warsaw” is one of the poems he read to the class and then to the larger audience that evening. It presents a narrator grappling with the violence witnessed in Warsaw during World War II and then the fate of his beloved Poland. I remember how in class he borrowed the Selected Poems and began to read that poem first in Polish and then in English. It was affecting and illuminating and dated, again, pointedly, 1945.

What are you doing here, poet, on the ruins

Of St. John’s Cathedral this sunny

Day in Spring?

….

You swore never to be

A ritual mourner.

You swore never to touch

The deep wounds or your nation

So you would not make them holy

With the accursed holiness that pursues

Descendants for many centuries.

Thus, marked once more by the year 1945 and invoking Warsaw and St. John’s Cathedral, the poem confronts the aftermath of violence and gives voice to humanity’s exposed condition in a world of severe conflict. One of the students asked for an explanation. He spoke first of the Warsaw uprising in 1944, during which there was a struggle between Polish insurgents and an occupying German army, and during one period in which the Germans killed as many as 40,000 civilians, a number that would climb to around 250,000. The point of the insurgency, however, was not only to rise up against the Germans but to gain Polish sovereignty before the Soviet army would gain control. Milosz thought to say that this was the beginning of the Iron Curtain and the Cold War.

But why a Cathedral dating to the 14th century?

Milosz explained that the Cathedral was a place of struggle between those Polish insurgents and the German army during the months of August to October. The Germans inserted a tank loaded with explosives into the Cathedral and drilled holes in the walls for explosives and blew up the Cathedral. He explained how Poland after World War II had become a satellite Communist nation under Soviet Russian influence. The point was that Poland did not gain independence after the war, which meant that after World War II and 1945, the war did not end for Poland. The country had been occupied by Germany at the beginning of the war and by Russian forces as late as 1963.

He asked the students then to consider that situation and also to consider the risk he, Milosz, took when he exiled himself from Poland, which meant losing a relationship to his art and to his language. And he asked the students to think about what it must be like to live in an atmosphere so terribly grim when Poland became communist. “It’s madness,” he writes, “to live without joy.” To which one might add, to live with a captive mind.

In his speech at the Nobel Banquet, December 10, 1980, Milosz referred to the last century as a century of exile and branded himself just so. What more, then, should a reader expect in this posthumous collection of poems written between 1946 and 1953? It is concerned with nothing less than the central issues of our time, or so wrote Terrence Des Pres in The Nation, calling Milosz’s work “the poetry of aftermath.”[1]

Yes, I was a witness. But I was never reconciled.

No one living will tear assent from my lips.

Anyone faithful won’t be conciliated.

If your Vatican lies broken

I will keep going, to bear in the windstorm

The aurea aetas from heart to heart.

—“Two Men In Rome”

The above lines are from the second section in Poet in the New World, Poems, 1946-1953. The italicized phrase translates as “golden age,” or at least as the two men are thinking in their promenade, a time of peace which suggests an ambiguity, their time symbolized against an idealized past or maybe just a time when life was more simple, more easy. Too easy, however, to cheat life with the coloring of “mythic” memory embracing such as if in a thrall, the merit of which is dubious. And yet if one gives some thought to the poem’s mysterious imagery, there might be something here not only symbolic but allegorical, much like that biblical moment in which two men are on the road to Emmaus.

Milosz, the Polish-American poet, prose writer, and diplomat, has been dead now for a bit over twenty years. His prose book, The Captive Mind, is a masterpiece tackling all the questions pertinent to political totalitarianism. To read the book is to read the story of how his Catholic faith supported him, especially during his World War II experience. His 1980 Nobel Prize bears the citation that here is a writer who “voices man’s exposed condition in a world of severe conflict.” The italics are mine, as is the use of the phrase to title this review.

The poems in Poet in the New World, 1946-1953, should be prefaced section-by-section by just such language since the speaker in these monologues indeed voices man’s exposed condition in a world of severe conflict. Consider, again, “1945, Warsaw” and that single poem “In Warsaw.”

What are you thinking here, where the wind

Blowing from the Vistula scatters

The red dust of the bubble?

But mourner the poet does indeed become writing lines that lament, poems of endurance when the heart feels as if a stone is enclosed and heavy-hearted but still the need to write dark love for a most unhappy land, this Poland. Milosz was again in Warsaw when the Germans bombarded the city at the beginning of the German invasion. When the Germans began burning buildings, he was part of a group rounded up and placed in a transit camp. He was rescued by a Catholic nun.

Perhaps the most striking poem, from my perspective, is the long “Treatise on Morals” which concludes section three, “1947, Washington DC” and the time of his exile. The poem has twelve pages ,which begin poignantly with the following lines:

Just what, oh poet, do you propose to save?

Can anything save the earth?

This so-called dawn of peace,

What has it given us? A few morning glories

Among the ashes. It gave hopes bile, the heart

Cunning, and I doubt it roused much pity.

Sardonic almost to extreme, with the poet arguing that his mission is not “To surround the future with empty magic.” “What’s the uses of an illusion of the future / If it blasphemes against our quotidian days / And does not share our confidence / Equally among our fellow citizens.” So this was his subject for the day, and yet “everyone thirsts for a faith.”

By comparison, the poet offers the argument that life in the new world, “1946, New York and Washington DC,” and the remarkable “ Child of Europe,” and a narrative of how life has become better than those left behind, those who perished. Living now in New York and Washington, the poet enjoys how the “lungs fill with the sweetness of day,” and how in “May so lovely to admire trees flowering.” Much better than those who were buried. The problem? To carry into this new world the memory of fiery furnaces from “behind barbed wires” and the endless autumn howling. “We, who remember battles where the wounded air roared in paroxysms of pain, We, saved by our cunning and knowledge. . . . . We sealed gas chamber doors, stole bread, / Knowing the next day would be harder to bear than the day before.”

Sardonically, at the end of “Treatise on Morals,” the narrator says, “I need to say this with some starkness: Before us lies “The Heart of Darkness,” and thus an ironic nod to Joseph Conrad. In the fifth section, “1949, Washington, DC, the poems traverse a more gentle embrace in which life has a different essence. In “A Little Negro Girl Playing Chopin,” the poem is absent the usual stark alienation and political implications or lacerating anger. The poem reads like a follow-up to William Carlos Williams, and so much depends. How to read the poem? When the world seems a hopeless place, note how “she places her dark fingers on the keys . . . And when the hall suddenly grows quiet, / The primrose of tone slowly unfurls.”

Since we know this collection aims to grapple with the reality of life emerging with the Cold War, the poet is less the poet who, with his “quill,” sets about to create the New World as the famed “City Upon a Hill.” If that were so, memory would become useless losing its power, if that’s the right word. He worries over those seven years that the world is again in ferment and poison with the illusion that all is well, dwelling it seems in order and peace, but which might again “vanish without a trace.”

Such would seem a more than usually sardonic mood, but the poet leaves the reader with the following lines from the concluding and consoling poem, “Notebook: Bons By Lake Leman.”[2]

Do you agree then

To abolish what is, and pluck from movement

The eternal movement as a gleam

On the current of the black river? I do.

One might trace these ending lines from Eliot’s “Burnt Norton” and “At the globe’s still point, where the Tiber unravels….

At the still point of the turning world. Neither flesh nor fleshless:

Neither from nor toward; at the still point there

the dance is.

There are still points, still spots of time, that are redemptive and about which the poet remarks in “Two Men In Rome”:

At the globe’s still point, where nothing changes,

There is a different compassion of a human kind,

Begun where the poet of memory ends,

In the great shining quiet of the still point.

Daniel James Sundahl is Emeritus Professor in English and American Studies at Hillsdale College, where he taught for thirty-three years.

[1] The Nation, December 30, 1978.

[2] Bons is likely the plural form of “bon,” which when translated from the French might mean something like “a good thing.” Byron paraphrases Psalm 137 in his Hebrew Melodies as does Eliot in “The Fire Sermon.”

Support the University Bookman

The Bookman is provided free of charge and without ads to all readers. Would you please consider supporting the work of the Bookman with a gift of $5? Contributions of any amount are needed and appreciated!