by Joshua Gibbs.

CiRCE Institute, 2018.

Paperback, 239 pages. $16.

Reviewed by Elizabeth Bittner

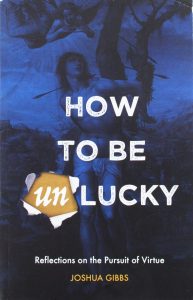

If we were to judge a book by its cover, we would likely steer clear of Joshua Gibbs’s latest work. Titled How to Be Unlucky, the book’s appeal is further tested by its cover art depicting the martyred St. Sebastian, bound to a tree and pierced with arrows. Fortunately, this is no how-to guide for misery and death, but rather reflections on the pursuit of virtue. Why does virtue matter and who cares anyway? Gibbs is well equipped to tackle these questions as he himself struggled with them for much of his early life.

As a student Gibbs did not see much use in striving for virtue. He was a slacker and on, as he puts it, a “slothful and lackadaisical trajectory.” Much to his surprise, his life path led from being a student in a classical setting to being a teacher in a classical setting. He came to realize that he was in over his head. Rather than retreating into pedagogic egotism to hide his embarrassment, Gibbs submitted to the great works he was truly encountering for the first time. The story of one particularly unlucky man from antiquity changed everything for him. Boethius and his Consolation of Philosophy “upended” Gibbs’s whole approach to teaching and life. As he remembers, “I read The Consolation at a time when I knew nothing at all. I read the book for the first time as I taught it, and it was the first work of philosophy I had ever really understood.” The teacher began to learn as he taught.

Gibbs came to see himself in his high school students. He knew what they needed to learn—specifically that mere memorization is not enough; that learning is inherently valuable; and that virtue, like anything else, requires practice. In The Consolation of Philosophy Gibbs found the key to reaching his pupils, which was, Gibbs notes, that “the confessorial teacher opens himself up to being judged by his books.” Stories of his personal failures and the lessons learned from them were what these teenagers needed to hear. Challenged by The Consolation to abandon his “favorite sanctuaries,” Gibbs encouraged his students to examine their own personal nooks and crannies and leave behind the familiar, comfortable nests where sin and mediocrity thrive.

The story of Boethius is both unnerving and enlightening. Boethius, faithful servant of Rome, has been falsely accused of betrayal and awaits execution. He is full of sorrow and self-pity. His death is unfair and untimely. It is the ultimate misfortune. What kind of reward is this for a life of service and loyalty? This is a valid question, but Boethius errs in assuming good fortune to be the reward of earthly deeds. This assumption renders good works and virtue mere commodities rather than something good in and of themselves. Lady Philosophy consoles the woeful Boethius, yet also admonishes and reproves. Her judgment: Boethius is too attached to the world. Accepting his impending demise is hard; death stings. Gibbs commiserates, but offers this: “The only way to escape the inevitable pain of death is to practice dying long in advance.” This mentality of “start dying today” is challenging to implement, especially when tomorrow always seems a better time for abandoning vice and embracing virtue. From experience Gibbs can justly advise: Start today. Practice makes perfect. Practice makes virtue.

For many, including Boethius, happiness is the obtaining of what is longed for. By this understanding happiness could be power, wealth, fame, sex, or any number of other worldly goods. It may seem that Fortune smiles upon those who receive the objects of their longing. But the satisfaction of worldly pleasures has its price. Gibbs states, “Silencing the soul that the body may enjoy pleasure is dangerous and disorienting.” Perhaps this is particularly true for those enslaved to secret addictions. Not getting caught in vice is not only a teenage concern. The “trance of habitual sin” is one that affects all humankind. Hell is described by Gibbs as the place where you get away with everything because there is no one around to tell you to stop. True happiness then, comes from open confession and acknowledgment of fault. It is not the indulgence of pleasure but rather being joyful and content with what one has. It is the recognition that good fortune is not a possession but a gift from God.

For Gibbs, classical education is more than reading and writing, lectures and exams. It is the formation of individuals into upright and full participants in humanity. Such education does not end with graduation. Education with the Great Books partakes of a higher and holier experience. Gibbs finds this same attitude in Christianity itself where the sacred suffuses the secular. He writes that all things partake of holiness because God is manifested in all things. And if God has made all things holy, then what we do truly does matter. Apart from station or situation, life has value, meaning, and purpose. Living sacramentally, Gibbs believes, is to live in simplicity of heart, accepting the reality of each day as it arrives. A consuming fear of the future is Satan’s ploy to take one out of the present, to rob one of peace and satisfaction. This ploy is the same today as it was in Boethius’s time. Gibbs brilliantly notes the difference between thinking of the future and taking thought for the future. For students beginning their life’s journey, this is an especially important distinction.

There is nothing new under the sun. The well-known phrase from the book of Ecclesiastes bemoans the drudgery and toil that is life. Gibbs understands how this saying is hardly uplifting; as he writes, it is a hard truth that hard work doesn’t entice a man to anything. What’s the point? What is the point of laboring physically, intellectually, spiritually, if death is the inevitable result? The answer he offers is hard but true: “The point of planting the field was not planting the field … The field is planted so a man might know God in the planting.” Expending one’s life in toil is only drudgery if it is done for material gain. There is something in striving after God that is worthwhile. Gibbs expresses it simply: “when our lives are lived sacrificially, they are not lost.” To the lament that nothing is new under the sun Gibbs replies, correct—so stop looking! Perhaps we should direct our gaze and attention to that which is above the sun. There we will encounter the new, the fresh, and the eternal. Perhaps this is why St. Sebastian is a fitting cover image after all. Sentenced to death and pierced with arrows for love of God, his gaze is not downward but heavenward; his expression not one of pain and misery but acceptance and hope.

And so, in a world that seemingly has no use for it, the practicing and acquiring of virtue does indeed matter. Great works of the past still have something to teach the present. Transformation is still possible. Does it require humility? Yes. Does it entail pain and sacrifice? Yes. But Gibbs shows us that the effort is worth it. What of it if obstacles arise (and they will)? Gibbs’s message is liberating: Live life! Live it with joy according to something greater than oneself. The last words of How to Be Unlucky are anything but calamitous: “When God gives you time to mourn, cry your eyes out. When God gives you a time to laugh, exhaust yourself in laughter. When God gives you a time to share in the lives of others, don’t hold anything back for yourself. Pour yourself out, and rise to Glory way over the sun.”

Elizabeth Bittner holds a B.A. in political science from The Thomas More College of Liberal Arts and a Masters degree in the humanities from the University of Dallas. She currently resides in rural Missouri.