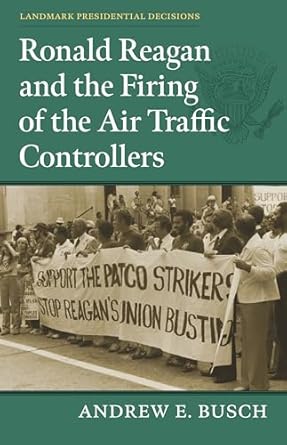

Ronald Reagan and the Firing of the Air Traffic Controllers

By Andrew E. Busch.

University Press of Kansas, 2024.

Paperback, 180 pages, $24.99.

Reviewed by Jason C. Phillips.

Rare has been the day since President Trump was sworn in for his second term that Elon Musk’s work with the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) has failed to make headlines. The work of DOGE, alongside President Trump’s stated desire to eliminate the Department of Education and other federal programs, makes Andrew Busch’s new book, Ronald Reagan and the Firing of the Air Traffic Controllers, a timely read. Busch is a Professor of Government and a George R. Roberts Fellow at Claremont McKenna College. This book is his second foray into the study of Reagan. He published his first work on President Reagan, Reagan’s Victory: The Presidential Election of 1980 and the Rise of the Right, nearly twenty years ago.

Busch’s new work is part of the Landmark Presidential Decisions series from the University Press of Kansas. The book traces President Reagan’s decision to fire the striking Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization (PATCO) workers in the autumn of 1981. Busch argues throughout that the PATCO strike deserves much more attention than it has previously attracted. The last few months have only increased the necessity for further study, though this does not suggest that either the firing of the PATCO strikers or the recent actions of Musk’s DOGE are necessarily bad. Rather, it highlights the importance of understanding how the Executive branch functions, from top to bottom. As Busch reminds us, “While the short-term consequences of the PATCO firings were not trivial, it was the long-term consequences that make it a presidential decision of real significance.”

Busch does a fine job of laying out the history of the formation of PATCO and its ultimate decision to go on strike in 1981. Busch reminds the reader that throughout the early twentieth century, both Democrats and Republicans were opposed to public sector strikes, highlighting how then-President Woodrow Wilson had sided with then-governor Calvin Coolidge when he broke the Boston police strike in 1919. Busch also notes that President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who signed the National Labor Relations Act (or “Wagner Act”) in 1935, was also against the idea of public servants engaging in collective bargaining. It was not until President John F. Kennedy signed Executive Order 10988 in 1962 that federal workers would have the right to organize, an act that AFL-CIO head George Meany called a “Wagner Act for public employees.” Unionization in the federal workforce would skyrocket throughout the next two decades, including PATCO in 1968. Busch notes that in spring 1970, PATCO “began what amounted to the first centrally planned, though lightly disguised, nationwide strike by a public employee union in American history.” The courts would reel PATCO in in 1970, but in 1972, President Nixon would acquiesce to them.

These successes, combined with their self-perceived importance, would lead PATCO to become more and more aggressive in their demands. After some setbacks in negotiations in 1978, PATCO would see a new leader emerge, Robert E. Poli. Poli became president of PATCO in February 1980 and was determined to take PATCO in a more radical direction. At the time, PATCO appeared to be in the driving seat. The union had engaged in slowdowns or sickouts in 1968, 1969, 1970, 1976, 1978, and 1980, but there had been little to no executive enforcement of the no-strike law. Further, PATCO backed the right horse in the election of 1980 by endorsing Ronald Reagan. Heading into 1981, PATCO would confidently ramp up for their negotiations with Reagan, Secretary of Transportation Drew Lewis, and Federal Aviation Administration Director J. Lynn Helms. Busch notes that two economic advisers also stand out as heavily involved in the incident for the Reagan administration: Martin Anderson and David Stockman. Stockman is an interesting figure, as the former Congressman from Michigan had been elevated to cabinet status as the OMB director. Stockman was seen as a rising young star, responsible for finding budget cuts, in many ways another parallel to Musk’s current DOGE. Stockman and Reagan would later have a falling out, but in 1981, he was at the peak of his prestige. Others mentioned as vital to the PATCO crisis include Craig Fuller, Robert Bonitati, Richard Wirthlin, David Gergen, and “The Troika” (Chief of Staff James Baker III, Deputy Chief of Staff Michael Deaver, and counselor to the president Edwin Meese).

Busch spends a significant chunk of the book describing how Reagan handled the negotiations and subsequent strike, while always coming out on top. While Busch does a great job in this analysis, one can’t help but wonder why Reagan’s previous experience as a union president of the Screen Actors Guild is not mentioned more often. In his final term in 1960, SAG actually went on strike for the first time under his leadership. Nor is Reagan’s time working for General Electric mentioned. Reagan’s time as a GE employee involved much, much more than just hosting one of America’s most popular shows during the Golden Age of Television, General Electric Theater. It involved countless GE factory tours and events, as well as speeches across America, which Reagan lovingly referred to as “the mashed potato circuit.” There were also the lessons he learned from GE executives Lem Boulware and Ralph Cordiner, as they battled with their own union. This whole period of Reagan’s life and political transformation is chronicled in one of the seminal texts of Reagan historiography, Thomas Evans’s The Education of Ronald Reagan, a work that is shockingly not mentioned in Busch’s endnotes or bibliographic essay. The Landmark Presidential Decisions series are thin volumes, so there are restraints and limits to what content makes it to the final draft, but the exclusion of this period of Reagan’s life stands out as a mistake in an otherwise excellent book.

The book makes a convincing case that Reagan expertly handled the PATCO crisis and of the long-term significance of this presidential decision. Busch goes into painstaking detail describing the negotiations, including the salary and working hours concessions that the Reagan administration made to PATCO in the June 22 contract. It was PATCO that made the decision to reject that contract and go on strike and force Reagan’s hand. As Busch put it, “Only the decision by the union to strike crossed Reagan’s red line and triggered his determined response.” Reagan was willing to hold PATCO accountable in a way that previous administrations had not been. This decision had a decisive impact on public-sector unions, especially in the federal workforce. Busch also cites Reagan’s Secretary of State, George Schultz, in making the case that the firing of the PATCO strikers had an impact on foreign policy because it taught world leaders that Reagan was willing to dig in and fight. Schultz later called it the most important foreign policy decision Reagan ever made. Busch even argued, “In the turbulent 1980s, in a world filled with well-armed and malevolent adversaries, that impression may have been the single most important prerequisite for the preservation of peace. Hence, of all the consequences of Reagan’s PATCO decision, this one may have been the most significant.”

Ronald Reagan and the Firing of the Air Traffic Controllers is a superb volume that quickly and efficiently tackles President Reagan’s decision to fire the PATCO strikers. This timely book is well worth spending a weekend reading and pondering.

Jason C. Phillips is an Associate Professor of History at Peru State College in Peru, Nebraska. He received his PhD in history from the University of Arkansas in 2019.

Support the University Bookman

The Bookman is provided free of charge and without ads to all readers. Would you please consider supporting the work of the Bookman with a gift of $5? Contributions of any amount are needed and appreciated!