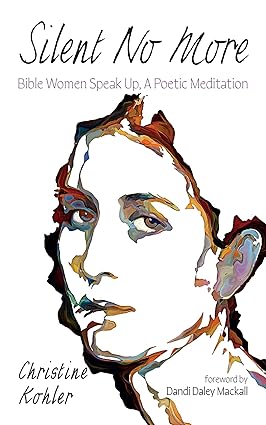

By Christine Kohler.

Resource Publications, 2024.

Hardcover, 78 pages, $25.00.

Reviewed by Annmarie McLaughlin.

Christine Kohler’s poetry debut, Silent No More: Bible Women Speak Up, A Poetic Meditation, follows multiple previous books that comprise an impressive variety of genres, ranging from young adult historical fiction to how-to guides on writing and music. The mix of poetic forms in this debut certainly reflects the author’s versatility: Kohler imbues a haiku with as much insight and emotion as a ten-stanza Reader’s Theater. Each poem is biblically rooted, but Kohler draws on extra-biblical sources and her own creative imagination to ponder what her characters may have been thinking during the pivotal moments of their mostly undocumented lives. The result is a beautiful exploration into the hearts and minds of the women of the Bible—both named and unnamed—that leaves readers feeling as though the women are imminently present, sharing their innermost thoughts and the overlooked aspects of their experiences. By shining a spotlight on the seemingly practical, worldly concerns of the selected characters, Kohler in fact raises deeply theological questions. The book claims to be suitable for Bible study and personal mediation; to this I would add limited academic settings, where the poems could serve as discussion-provoking supplements to the biblical texts on which they are based.

Kohler zooms in on her characters as they stand poised at significant crossroads. The book opens with “Eve’s Lament,” which depicts Eve lingering at Abel’s grave as Adam gently prods her forward, urging her to join him in creating another child who is “Bones of our bones. Flesh of our flesh” (cf. Gen 2:23). A repentant Eve expresses regret over being forced to abandon her sons. “This is my fault. . . Sin of my sin,” she mutters. Subsequently, she sprinkles dirt on Abel’s feet and thinks, “Dust to dust. . . . Ashes to ashes.” Eve’s complaint that the pain of losing Abel is worse than the pain of giving birth highlights the extent to which the punishment inflicted upon her in Genesis 3:16— “I will intensify your toil in childbearing; in pain you shall bring forth children”—was a vast understatement. Her wish that she had “cut down the Tree of Knowledge” raises the question that the story of the Fall inevitably provokes: If God knew what Adam and Eve were going to do, why did he put the tree there in the first place?

“Naamah’s Indignation with Noah” digs further into the same theme as the serpent who initiated the trouble becomes the foil for Noah’s wife. Naamah frets and fusses over the fact that her husband, who is presumably busy with other preparations, tasks her with herding the animals onto the ark (“that ludicrous house”), including, of course, “that vile creature.” Behind her irritation that she must “hunt down, then pick up those belly-slithering fanged devils with forked tongues” lies the most prominent and burning theological question of every age: “Why does God permit evil?” Yet despite fretting like an over-burdened housewife, Naamah has mettle, noting that she would rather “chase down spiders” than capture the snake. Arachnophobia be damned.

I would be hard-pressed to identify a favorite among the many poems, but the pairing of “Rebekah’s Supplanter” with “Leah, Matriarch of the Tribe of Israel” ranks fairly high. In the first, a villanelle, Rebekah mourns the pending flight of Jacob following his ploy to claim Esau’s birthright. Though not explicitly stated in the biblical text, the consequence of the scheme seems to be that mother and son never see each other again. Kohler’s poem suggests that Rebekah had not previously considered the potential fallout of the deception; even here, it is not entirely clear that she fully grasps the implications. But as the poem concludes—–“What good is a birthright/if my son spends life in flight?”—the reader knows that this far more painful reality is actually what lies in their future. Rebekah’s fragile hope for an eventual reunion is made all the more poignant by this knowledge.

In the Bible, the cost of deception for Jacob extends beyond lifetime separation from his mother. In turn, he is notoriously deceived by his Uncle Laban into marrying two sisters, Rachel (his true beloved) and her older, less attractive sister, Leah. The rivalry that ensues between the sisters is legendary and undergirds the existence of the twelve tribes of Israel. Though the Bible describes a beautiful scene in which Jacob and Esau eventually reconcile, it only hints at a truce between the sisters when they unite with Jacob against their greedy father and claim what is rightfully theirs. But Kohler’s poem probes a moment we never read about in the Bible: Leah’s reaction to the untimely death of Rachel. Leah’s biblically narrated boasting about her fertility creates a strong contrast to Kohler’s musings about Leah’s devastation at the loss of her sister, which takes on a stark physicality: “Drawing my sister’s head against my womb, I spread my legs/around hers. Why not? We are one flesh, one blood, one tribe.” Leah even goes so far as to exonerate Jacob for his favoritism: “I cared for my sister as a child, taught her to draw/the water that drew Jacob to her. To us./ I did not blame Jacob for loving Rachel more.” Though Kohler clearly takes some creative liberties here, why can we not imagine that in a world where sin begets sin, forgiveness can also beget forgiveness? If Joseph could forgive his brothers for their cruel betrayal, cannot Leah also consider Rachel’s sons “as much mine as the fruit of my womb”?

Fittingly, Kohler transitions into the New Testament with “Bethlehem Nights,” a haiku that is worth repeating: “Mary rocks her son/Soft winds whisper lullabies/On wings of angels.” The familiar image of a loving mother lulling her child to sleep is thus transformed into a reminder of Jesus’ divinity: who but Mary and Jesus would be serenaded and cradled in this way, as if in heaven already, with the natural forces and angelic powers of the world acknowledging their status?

Three poems are devoted to the saga of Martha and Mary. Kohler harmonizes Luke’s account of Martha complaining about her sister Mary (Luke 10:38–42) with John’s account of the Raising of Lazarus (John 11:1–54) and Mary’s subsequent anointing of Jesus’ feet (12:1–8). The result is a thoughtful epilogue to the unresolved tensions of these events. In “Martha, Be Not Troubled,” the beleaguered sister reacts to the recent stress of nearly losing her brother, Lazarus, their “protector against ruin,” by remembering Jesus’ response to her frustration with Mary. Readers are reminded of the extreme vulnerability of women in the ancient world in the absence of male providers. Martha’s laughter as she prepares a meal for her beloved brother and his Savior is coupled with the joy of her gratitude; together, these emotions banish the “panic” and “fretting” she previously experienced, signaling the extent to which Jesus’ actions have relieved them of worry. In this way, Kohler helps readers imagine the peace that comes to the household of Jesus’ close friends in a way that is consistent with the spirit of the biblical events.

I take issue with some minor details throughout the book, and in particular with “Abraham Pimped Out Sarai.” Part of the book’s charm lies in its ability to transport us to a land that is completely “other,” that is, the world of Ancient Israel, and into the hearts and minds of its most vulnerable characters. But upon reading references to the “#metoo” movement amid the plight of Sarai and Hagar, I felt as though I had been unceremoniously dropped into the middle of a modern urban protest. The poems work better when contemporary articulations of recurrent problems are left aside and the reader is instead immersed in the actual world of the characters.

I was also somewhat surprised at Kohler’s interpretation of the story of David and Bathsheba. Art and movies famously portray it as an adulterous affair, but the biblical story contains many nuances, not least of which pertain to whether or not Bathsheba was complicit in the relationship. When Bathsheba bathed on her roof, did she know that David could see her? The biblical text is vague, but either way, a woman has the right to bathe in the only place accessible to her, and David was supposed to be away at war with his soldiers, not lounging on his rooftop spying on his subjects. After all, “consent” is not really possible when the king’s men show up at your door and escort you to the palace. Yet Kohler, who has no qualms labeling Abraham’s dubious actions as “sex trafficking,” depicts Bathsheba as repenting for her “adulterous lust” and betrayal of her husband.

Although “A Proverbs 31 Parody” reinforces the tendency to dismiss the biblical acrostic as presenting an inaccessible model of female virtue—a tendency I believe is unfortunate—it is done with such lightheartedness and humor that I found myself willing to play along. Told from the perspective of a Yiddish-speaking woman who kibbitzes about her husband, her household chores, and the pressure to imitate the model wife depicted in the Proverbs poem, the parody made me want to brew a cup of tea for the poor woman and invite her to take a load off. And that’s the real beauty of the book: Kohler’s ability to make readers feel as though the women are sitting right beside them, pouring out their hearts. You just want to hold their hands, pat them on the shoulders, and tell them it will be all right, that God is by their sides, listening to them, responding to their prayers. But truthfully, most of Kohler’s characters already know that. The Zidon widow praises God and professes her belief that Elijah is a man of God; Esther declares, “Though I don’t know God’s purpose,/I yield myself to his gifts,/ do my best to be prepared”; Jairus’s wife declares Jesus to be the Messiah; and Paul’s sister closes the book with a prayer that echoes the words of Jesus himself on the cross: “I commend my son into your hands, to do your will, my God and Savior.” So even as these women face challenges and situations that most modern women can scarcely imagine, much less expect to experience, they offer timeless reflection and wisdom from two and even three thousand years in the past. In the words of James and John’s mother (“Salome’s Request for Her Sons”), even when Jesus does not tell us exactly what we want to hear, we can, like these women, “hear hope.”

Annmarie McLaughlin is Associate Professor of Writing and Research, and Associate Professor of Scripture at St. Joseph’s Seminary, Dunwoodie, NY.

Support the University Bookman

The Bookman is provided free of charge and without ads to all readers. Would you please consider supporting the work of the Bookman with a gift of $5? Contributions of any amount are needed and appreciated!