By William F. Buckley, Jr.

John Wiley & Sons Inc., 2004.

Hardcover, 212 pages, $19.95.

Reviewed by Michael Lucchese.

As conservatives mark the centenary of William F. Buckley, Jr.’s birth, one of the most-celebrated aspects of his remarkable career is the unshakeable anticommunism he made the heart of our movement. As George F. Will often remarks, the National Review founder’s decades-long struggle against the Soviet Union was so consequential that an argument could be made that “Bill Buckley won the Cold War.” Recently, The University Bookman itself published two fine essays examining Buckley’s commitment to one of the twentieth century’s great crusades, especially on its domestic front. [See here and here.]

And yet Buckley’s anticommunism was never solely about the negation of an ideology, important as such a disposition is, or even the maintenance of order in the United States alone. Without committing the neoconservative error of setting up liberalism as a counter-ideology in a futile quest for perpetual peace, he nonetheless understood the collapse of the USSR as a victory for Western civilization—even a proof of the superiority of our way of life. The West, sustained by traditions worth conserving, had triumphed over totalitarianism at long last. For Buckley, winning the Cold War was about affirming the eternal value of the ordered liberty we have inherited.

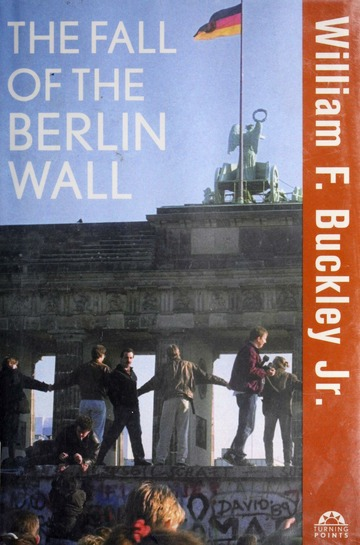

This triumphant civilizational hope suffuses Buckley’s short and oft-neglected work The Fall of the Berlin Wall. Not only laudable as an accurate and rousing history of one of the Cold War’s most vital fronts, it also stands as a powerful reflection on the nature of freedom itself. “Berlin,” Buckley put it, “always seemed a very conspicuous linchpin to that enslaved region of the postwar world.” The Wall itself represented the perennial confrontation between freedom and tyranny, and therefore images of Germans tearing down the monument to totalitarianism have become icons for the end of the Cold War. Without treating the Fall as a historical inevitability, Buckley searched out the greater meaning behind half a century’s events.

At the end of World War II, Berlin lay in ruins—Buckley reported that 39 percent of the city’s buildings had been destroyed, and fifty thousand of her souls lost. It was also divided between the Allied powers and the Soviet Union, each occupying a part of Germany and attempting to reconstruct the broken nation according to their regimes’ principles. Although the book itself is primarily concerned with a narrow span of years, Buckley began by setting the stage according to a profound historical consciousness. The situation that developed in Berlin in the decades after the War was not merely the result of a confrontation between two competing hegemons, but also the long march of centuries of conflict between the European powers. Even in this slim book, Buckley offers readers a much wider view of the world than his reputation as a right-wing firebrand might suggest.

But what makes Buckley’s work truly remarkable, in part, is his conviction that ideas have consequences. Many academics writing about the Cold War strive for a false sense of objectivity and portray Western leaders and their Soviet rivals as essentially the same, motivated by realpolitik security concerns or other cold rationalisms. Buckley, by contrast, honestly depicted the ideological aims of his communist antagonists. He understood that they were utterly committed to the totalitarian vision, and the decisions they made about Germany and the Wall must be understood with reference above all to their ideology.

Take, for example, Buckley’s portrait of Walter Ulbricht, the East German politician most responsible for the construction of the Wall. Ulbricht was, he wrote, a “true believer” in the communist cause—Buckley notes with morbid humor that he even grew a goatee in imitation of his hero, Vladimir Lenin. Even more troublingly, the Soviet puppet was a vocal and eager supporter of the most aggressive policies against both the West and the Eastern European peoples, as his masters in Moscow advanced. Ulbricht worked overtime to revolutionize East German society by collectivizing economic policies and suppressing critics using classic totalitarian methods (including the creation of the terrifying Stasi secret police force). And he was willing to lie to his Western counterparts in pursuit of his revolutionary goals. Indeed, Buckley demonstrates that the entire cast of communist leaders behind the construction of the Berlin Wall was a truly revolutionary force—they wanted nothing less than the destruction of the Western order root and branch, replacing it with utopian delusions which could only be sustained through deadly and inhuman force.

Buckley’s honesty about men and motives is nothing less than an indictment of the politicians labelled “Cold War liberals” and their latter-day defenders. Although many Western liberals were no doubt earnest opponents of totalitarianism’s worst aspects, they rarely acted with the kind of urgency and resolve necessary to counter the Soviet march through Eastern Europe. They were just too unwilling to confront the truth about what Ronald Reagan would call the “evil empire,” too eager for negotiation and cooperation and coexistence with Moscow to recognize the existential nature of the conflict. Buckley was an almost prophetic critic of this appeasing attitude in his columns and other writings throughout the Cold War, and knowing his role in organizing an anticommunist movement lends his effort at writing a history of the era a certain Churchillian quality.

Another way in which Buckley distinguished himself from the Cold War liberals is that he refused to turn The Fall of the Berlin Wall into a simplistic morality play. Despite the philosophical profundity animating the work as a whole, he never lost sight of the historian’s ultimate responsibility to narrate the events of the past as they actually happened. Buckley was therefore always sympathetic to the ways contingency and uncertainty shaped them. The Cold War liberals, by contrast, possessed a sort of ideological confidence that Soviet tyranny’s internal contradictions would eventually collapse the regime from within. Their approach to security policy was always hampered by this attitude; they simply did not believe in mobilizing the full strength of the West to oppose communist aggression.

Given this attention to contingency, Buckley did not only focus on the heroism of the few political leaders in the West who bravely opposed communist tyranny at the policy level—he also wrote movingly of the individuals and groups of civilians who worked to free dissidents trapped behind the Wall. Midway through the book, for instance, Buckley highlighted the efforts of West German university students to smuggle the oppressed past the barbed wire or through sewers and hastily-dug tunnels. Theirs was a truly desperate struggle, and while it did not liberate the hundreds of thousands consigned to Stasi oppression, it nonetheless stands as a moving testament to the universal human longing to live free.

At their absolute best, Western leaders also adopted the freedom-loving spirit embodied by ordinary Berliners. John F. Kennedy’s famous “Ich bin ein Berliner” speech stands out as one such example. Unlike many of the appeasers in his own administration, the young president seemed to understand the stakes of the Cold War. But unsurprisingly, the Western statesman Buckley lavished the most praise on Ronald Reagan. He refused to take the fatalistic approach to the Wall that so many advocates of détente or appeasement did. Reagan did not believe that a divided Germany or even the Soviet Union was an eternal fact to which the West simply adjusted. Instead, he worked tirelessly to actually win the Cold War and consign communism to the “ash-heap of history.” Buckley especially celebrated the much-derided “Star Wars” missile defense program and associated military buildup, not only for their strategic soundness but also because they demonstrated Western resolve after decades of apparent decay.

The example of Reagan demonstrates that statesmen and citizens alike who opposed communism in the twentieth century were motivated by more than mere desperation in the face of tyranny or ideological liberalism. The conservatism of the 1980s, the conservatism that won the Cold War, was sustained by a deeper faith—one which Buckley was instrumental in summoning. National Review only plays a cameo role throughout the text, but it is no exaggeration to say that the magazine and the movement it represented inspired millions to fight because it reminded them of the great civilizational inheritance global revolution imperiled. The destruction of the Berlin Wall presented a moment to restore the principles of human dignity that had long been the greatest legacy Europe offered the world, and Buckley’s little book is, in its subtle way, a beautiful reflection on this opportunity born of faith.

Sadly, though, the West did not fully capitalize on the victories of 1989 and 1991. Rather than taking steps to consolidate American leadership on the global stage, opportunistic politicians of both parties declared “mission accomplished” and acted as though tyranny had been defeated in all its forms. As a result, partly due to Western incompetence, Russian despotism, Chinese communism, and the Islamic Revolution, each now threatens to undo the miraculous end of the Cold War. These tyrant regimes seek to establish their own iron curtains and roll back the influence of the West in every possible way, replacing a world order built on ordered liberty with vicious ideology. Another storm is gathering, and the West is woefully unprepared to face the challenge.

Nevertheless, The Fall of the Berlin Wall should offer us some measure of real hope. The conservative’s vocation is to remind the world that the soul was made for eternity, not bondage in barbed wire. We have the examples of great statesmen, writers, and thinkers to inspire our efforts at defending a humane freedom. The example of Buckley’s life and work, which truly culminated in our last true victory over totalitarianism, is one of the best conservatives could look towards now.

Michael Lucchese is the founder of Pipe Creek Consulting, an associate editor of Law & Liberty, and a contributing editor to Providence.

Support the University Bookman

The Bookman is provided free of charge and without ads to all readers. Would you please consider supporting the work of the Bookman with a gift of $5? Contributions of any amount are needed and appreciated!