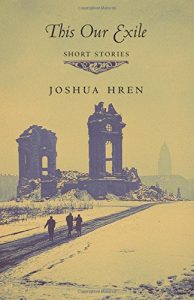

by Joshua Hren.

Angelico Press, 2017.

Hardcover, 131 pages, $22.

Reviewed by Trevor C. Merrill

The twelve stories in this slender but powerful volume bring the everyday and the eternal together in compressed, often dreamlike sequences, many ending in a shock of surprise, violence, or revelation. From a young artist facing the financial obligations of impending fatherhood to a disgraced businessman seeking judgment no human jury can supply, Hren’s characters are cast into a world shorn of easy consolations. They find freedom through the sort of internal restructuring that never comes without a healthy dose of pain.

The collection features disparate characters, including loving young couples, Lebanese refugees, a serial killer, and bickering divorcées. Many of the pieces were published separately in literary journals (one under a pseudonym). Yet this is a coherent whole, not a jumble. Two of the stories—“Wrecking Ball,” which opens the collection, and “Gates of Eden,” in ninth place—feature the same main character. Many involve grown children wrestling with parental ghosts and demons, while others ( “Control” and “In a Better Place”) show parents confronting the terrible seriousness of giving—or taking—life. References to Wittgenstein and Kierkegaard (the last story in the collection, an example of “flash fiction,” is entitled “Concluding Unscientific Postscript”) offer a philosophical throughline. And a common theme of transformative suffering and sickness links the stories, making This Our Exile into an extended meditation on, and demonstration of, how the “action of grace changes a character,” as Flannery O’Connor put it in a 1958 letter.

Given Hren’s chosen form—the short story—and his Catholic vision, O’Connor is an inevitable point of comparison. He has learned from her deeply enough to be able to acknowledge the influence without remaining in thrall to the master. In “Control,” a stricken father cries for his departed girlfriend and mourns their “canceled child,” aborted against his misgivings. He digs a tiny grave, and lights a candle that he has pulled from “our junk drawer”:

The explosion that bit my ear and screamed until nothing but sirens filled my hearing told me I had grabbed one of the firecrackers Cecilia Jade bought on the Fourth of July and left behind. Slowly, I could make out nothing but the sound of silence, a terrible declaration of independence from the white noise of this world.

This violent eruption recalls O’Connor in the way it turns the funereal into a dreadful, and wholly unsentimental, flash of celebratory joy, detonated by surprise for both character and reader. There follows an unexpected sweetness, and a foretaste of the divine, as temporary deafness mimics a contemplative silence: “A sound that has gone from sour to sweet like an apple bitten early but left on the tree until it bruises but ripens entirely. A noise that sometimes speaks in the language of God.” From the most unlikely material Hren has fashioned a path from sin and guilt to an interior monastic retreat.

Similar moments of reckoning punctuate other stories. In “Wrecking Ball,” the hero, Blaise, “still clung to the plot which he had given his life.” He dreams of becoming an artist, but knows that major upheaval is on the way: his wife is newly pregnant. On the way home from a late-night drink with friends who reveal themselves to be more acquaintances of convenience than true companions, Blaise’s bike gets a flat. Carrying the now-useless thing on his shoulders, he’s forced to walk home through the empty, darkened streets and happens upon the ruins of the brewery where his father and grandfather once worked. Within the abandoned walls, his hellish descent (the story begins with an epigraph from The Inferno) leads him into confrontation with shades from his past, and with an otherworldly homeless duo. The journey ends with its hero in prayer, his legs wrapped around a swinging wrecking ball, having arrived at a position of “steady, sober acceptance of unknowing,” beyond adolescent cynicism. The pressure of his “cold palms against the colder metal” as he ascends a piece of heavy equipment cannot fail to recall Dante’s chilly ninth circle, and this story reads like an ingenious mini recapitulation of the ancient work. Yet Hren is content to evoke, rather than straining for one-to-one correspondence.

Blaise returns in “Gates of Eden,” in which the motif of salutary destruction is just as prominent. He follows his neighbor Abdul into a church to contemplate an icon of the Black Madonna. In the course of the story Abdul expertly wields an axe to 1) kill a chicken that had provided his hungry family with eggs; 2) slice a student loan collection notice in half; and 3) punch a hole in a stained-glass window depicting “an image of Eden, emphasis on the angel’s fiery sword, its flames flicking Adam and Eve away.” In the church where he and Abdul are kneeling, the broken window holds Blaise’s fascinated gaze, and offers an emblem of Hren’s aesthetic, both in its (our) brokenness, and its depiction of paradise guarded by purifying fire, and a sharp blade.

Hren’s characters, here and in the collection’s other stories, find no easy point of stasis in the here and now, no neat reconciliation with the world. They are sick, destitute, or besieged by phony corporate and media narratives. But like Abdul, in literal exile from his native Lebanon, they experience hardship as a means of encountering a truer freedom. Cole Fedd, the materially comfortable but spiritually famished hero of the collection’s final story, must come to terms with words he heard from his father long ago: “Cole, it ain’t easy having everything. It’s the hardest thing.… Everything must go, Cole, before you can be free. It’s why I never met a free man all my life.”

One of the surest signs of freedom in any literary work is the presence of humor. Hren excels in a quiet form of hilarity. In “Sacré Coeur,” a mother of relentlessly modern disposition is baffled by her daughter’s forays into self-mortification. She catches the girl reading a volume by St. Margaret Mary Alacoque. “I read the book while Marie was asleep the other night,” she tells her ex-husband over the phone in a state of exalted incredulity. “Couldn’t put it down I was so disturbed. I even accidentally underlined some parts.” Similarly understated funny moments crop up throughout the collection. They are a kind of knowing, a way to get at the characters’ irrepressible and sometimes unconscious longing for something to believe in beyond themselves.

Hren’s prose also deserves mention. It is rich in concrete details, but also layered with poetic language, as in this description of a father’s flight of fancy as he prepares breakfast for his daughter: “And he imagined his hand, gloved in white muslin, lifting a silver, half-sphere plate covering—something like the top of a government building or a basilica—and presenting her the twisted black writhes of bacon.” In another story, a young man who has stumbled upon his estranged father working in a restaurant turns back to the table where his girlfriend is sitting and spots her teeth, “which almost glowed (she admitted, when I once made an off-handed comment, that she had started brushing with coconut oil and turmeric before she posted her profile picture to the dating website, one more thing I found refreshing: she was not vain, but also not quietly self-conscious).” These examples, chosen practically at random, give a sense of Hren’s sturdy, baroque style. He uses the mundane—bacon, teeth—as a surprising vehicle for beauty, but also to provide human and spiritual insights (in the story set in the restaurant dishes become “so many dirty vessels waiting to be ferried from the infernal shores through the machine that would make them pure again”).

Hren is a writer and critic, but also a publisher. Many will be familiar with Wiseblood Books, his labor of love that has contributed to a recent resurgence in Catholic fiction. Here the taste informing that enterprise is tangibly distilled. Hren accepts that he may be writing mostly for an audience of believers (like Wiseblood, his publisher, Angelico Press, specializes in Catholic works). References to Catholic ritual and concerns—guilt, suffering, the sanctity of life—and sprinklings of liturgical Latin appear throughout. The effect is not one of narrowing, however. The particular and the universal complement each other. Hren’s aesthetic is Catholic, but thus also, necessarily, catholic, rooted in the Christian realism of an O’Connor, but also in the cornucopian vitality of a Balzac (memorably referenced in one story) or a Joyce. A whole European cultural tradition is refracted in these unmistakably American pages. In short, there is something for everyone in this engrossing, diverting, and nourishing book.

Trevor C. Merrill is the author of The Book of Imitation and Desire: Reading Milan Kundera with René Girard (Bloomsbury). His essays and reviews have appeared in Education & Culture and The American Conservative, among others.