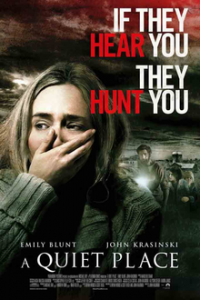

Directed by John Krasinski.

Paramount, 2018.

Run time: 90 minutes.

Reviewed by Ryan Shinkel

Apocalypses are one way to get religious at the box office. End times unveil moral character as wheat from chaff: the hopeful sacrifice for a better future while the despairing embrace annihilation. This revelation need not mean abandonment to our hells, but an occasion for grace. Divine mercy breaks into lives as a “eucatastrophe,” a reversal of misfortune at bleakest hours. When monsters knock and despair seems rational, pray for a miracle. This summer, an alien-horror film matched this pattern. A Quiet Place (2018), a post-apocalyptic film from John Krasinski, shows families ruptured by cataclysmic times.

The sound production of A Quiet Place fits its title. In an unexplained invasion, creatures hunt by listening for any human noise above a whisper. The movie sustains minimal audible dialogue throughout because its characters, the Abbotts—a family whose eldest child, Regan, was born deaf—use sign language as they go about a life on their sound-proofed farm that feels like something out of Wendell Berry. Brief pictures like a chalked Shakespearean sonnet and grace before dinner show how homeschooling and prayer help form the Abbotts’ monastic existence of father, mother, and three children. Under threat every moment even in their home, the parents use all means to ensure the kids are alright.

Famous for his Office role as Jim, the straight man to Steve Carrell, Krasinski is the script co-writer, directs the film, and plays Lee Abbott, a bearded engineer, survivalist, and father wearied from every surety undertaken, from footpaths to cameras. His real-life wife, Emily Blunt, plays his film-wife Evelyn Abbott, a doctor and mother. Their mode of being, less helicopter-parenting than old-school childhood with alien-invasion precautions, shows its difficulties: no guarantees exist to protect the progeny. Their youngest, Beau, a boy with breathing difficulties, is taken in the first scene, set eighty-one days after the invasion. His toy rocket sounds as they exit an abandoned pharmacy; we see Lee rushing and failing to prevent an alien from grabbing Beau. This immediate loss shows the threat level.

Krasinski’s direction shows great craft. Every scene, whether silent, full of natural sound, or playing orchestral music, offers a peaceful rustic existence interruptable, anytime and without warning, by aliens. Takes on this Death-in-Arcadia setup vary by political and religious commitment. Critic Richard Brody hysterically charges the director with anxiety projection of a white majority threatened by foreign invasion, but columnist Ross Douthat notes the way that—insofar any connection exists between film and reality—the movie actually undercuts a “male-paternal fantasy of real estate and retreat” whereby a farmhouse can escape hard times, for creatures still haunt their familial isolation of grain silos—a parable less of white flight than Lyme disease. The more theological takes are more insightful.

The story cuts to a year later. Deaf Regan, who gave Beau the noisy toy, is hurt and resentful as Lee takes her brother, Marcus, to a waterfall to be shown “you don’t have to be afraid”—specifically of speech—while her mother Evelyn is very pregnant. The overall question in the film is their decision to have another child when babies are noisy, Beau is gone, and the other two have to be raised in post-civilization: any human remnant is underground, while those above commit suicide by shouting. Fatherhood is not easy: Lee must teach Marcus how to be a man, reconnect with and reassure Regan, continue to tinker with hearing aids and think about potential invader weaknesses, and also ensure a safe birth. And neither is motherhood: Evelyn must teach Regan and Marcus, work the farm, endure labor for her new child, and all the while work with Lee in an equal partnership of wife and husband. In an Oscar-worthy performance, Blunt is less Brady Brunch than Amazon: bodily injured, she gives birth in a tub as the monsters hunt inside, and takes a shotgun to them after the birth. This child is perhaps the first born post-apocalypse. And Lee, in an act of sacrificial love, saves his children as his audio inventions later help address the extraterrestrial threat.

Three complementary reasons, besides genuine thrills in an otherwise stunted summer theater, explain this film’s appeal. The embrace of life in a world of monsters makes audiences pulse and ponder. The characters’ first three were born predisaster. Why have another rather than terminate the unborn child? In the Washington Post, Sonny Bunch argues that A Quiet Place shows the meaning of being pro-life beyond narrow partisanship—rather “in the sense” of “pro-living.” Mere survival is empty. Human flourishing indicates that “a life without family” is a sad “life without a future.” The Abbotts’ difficult but “homey” existence, despite the dangers, is “filled with love.” They do not need another child for any utilitarian reason, but that is not the point: the new baby Abbott is hope saying yes to life. The film helps audiences understand the outlook that, as “the universe once appeared out of nothing, a fact that reasonably seems to induce the strange vertigo of awe,” so “the formation of a new human being is not so different from this,” as Matthew Lee Anderson writes in Vox, citing Hannah Arendt’s recognition that the newcomer possesses the capacity of beginning something anew.

Alongside Sonny Bunch’s assessment of this “nearly perfect horror film,” is its thematic religiosity, earning A Quiet Place a nod from theologian and cultural critic Bishop Robert Barron as “the most unexpectedly religious film of the year.” The family’s monastic life—silence, study, prayer, agronomy, and household virtue—constitutes a domestic church. Krasinski, perhaps showing his devout Catholic formation by Polish and Irish parents, has the monsters—strikingly symbolic of sin and spiritual warfare—defeated with christological overtones.

At the end, after Lee mouths to Regan, “I love you; I have always loved you,” and then sacrificially shouts to draw the monsters away from surrounded Regan and Marcus, his family discovers that the hearing aids set to a high frequency immobilize the creatures, as Evelyn draws them to her shotgun. Lee’s sacrifice and their victory over reigning death-dealers, Barron notes, is highly reminiscent of Christus Victor, a patristic approach to the Atonement: the cross is a eucatastrophe whose apparent success for the devil means creation is liberated in Jesus’s rising. “O Death, where is thy sting?” writes Saint Paul; “O Grave, where is thy victory?” In a story of life after apocalypse, the Abbotts reveal a domestic church whose birth, despite monsters on the farm, wagers on the human future.

This apocalyptic storytelling also reveals hope, not in real estate and retreat, but in little platoons. In his Hedgehog Review essay, “The Apocalyptic Strain in Popular Culture,” Paul Cantor examines why films and television series portray human “civilization reduced to rubble” as “the few survivors” must “live a primitive existence in terror of monstrous forces unleashed throughout the land.” Perhaps there is “some weird kind of wish-fulfillment at work in all these visions of near-universal death and destruction?” His answer is yes: this ultimate nightmare reimagines the American Dream. Portrayals of life after societal collapse are modern Westerns often showing communities re-founded by basic American grit. In “an image of frontier existence” and risky conditions, the audience sees how “to manage without a settled government” and face “the challenge of protecting oneself” and family by “learning the meaning of independence and self-reliance.”

Apocalyptic films allow Americans, Cantor argues, to envision our most essential natures without state apparatuses. Apocalypse returns us to a state of nature to make what new social contract we deem best. Zombie films, especially, exhibit this tendency, with the walking dead as the new Indians and the living as the new pioneers. But visions do conflict between globalism and localism: in World War Z (2013), the U.N. commandeers the American navy as nation-states collapse, yet an international “expert” discovers an inoculation cure. In The Walking Dead (2010–), families reunite, homeschool, and use guns for survival in local associations as government centers explode and officials isolate themselves, and most organized groups of survivors want to live in mutual peace free from overlords. In Krasinski’s vision, the natural family plays defense but its members can save each other by mutual love and sacrifice. The family that prays together slays aliens together.

If apocalyptic stories return us to a state of nature, A Quiet Place displays the virtues of family life as more natural than the wayward individuals who commit suicide to break the silence. The film gives notes of hope for raising new generations and points to the grace that is new life. What Krasinski shows is a trust in the family in cataclysmic times. If this film has any relation to parenting today, it is that there is no quiet place from the monsters we have made, yet love is so natural as to be familial. Life after the apocalypse is not too bad at the box office.

Ryan Shinkel is a historical researcher for American Bible Society and a graduate student at St. John’s College in Annapolis, Maryland.