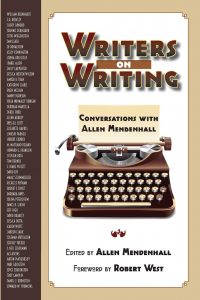

edited by Allen Mendenhall.

Red Dirt Press, 2019.

Paperback, 230 pages. $16.95.

Reviewed by Elizabeth Bittner

Writers on Writing is a superb collection of interviews conducted by Allen Mendenhall with established Southern writers, as well as those new on the scene. An accomplished author in his own right and editor of the renowned Southern Literary Review, Mendenhall’s conversations do much to highlight and celebrate the rich and varied nature of the Southern literary tradition. The interview format appeals to Mendenhall: “You just follow your curiosities and hope your interlocutor is open and honest.” Perhaps Mendenhall just knows the right questions to ask. Perhaps these writers are just great at providing engaging answers. As one continues reading, it becomes apparent it is a combination of both.

In his foreword to this collection, Robert West, a professor and editor from Mississippi, points out that Mendenhall’s interviews are not simply rote questions followed by equally rote answers. He is struck by the “sense of mutuality” that Mendenhall achieves in his conversations with writers from across the literary spectrum. West explains that “repeatedly we find two people having genuine exchanges—for the benefit of any who might enjoy and learn from them later. Mendenhall’s friendship with some of these authors enlivens those interviews to a special degree, but here also are first encounters that result in reflective, valuable dialogue.”

What makes this collection so fascinating is the broad range of current Southern writing. Southern literature has achieved great heights and depths in conveying the complexity of this region. Not just magnolias and sweet tea, deep and enduring elements are present here. This literature is far more than a lamentation of the Lost Cause (though the Civil War does loom large in the canon); it encompasses a wide range of topics across poetry and thrillers, short stories and mysteries, novels and romance and children’s stories. Amish and Edwardian themes also find a home here, as well as “Southern Gothic” works. If you think you know the South, you’ll find there is more to learn!

In these forty-seven interviews Mendenhall speaks with old friends and makes some new ones. He displays a keen understanding of the Southern literary tradition and its unique place within the nation and the world. There is pride in these Southerners, whether native-born or transplants, a sense of place that defies mere location; it is heart and mind and soul. No matter where in the world they may be, the South is home, and it is this sense of place, of belonging, that grounds Southern writers deeply in their tradition.

Mendenhall makes each exchange personal, but he also asks recurring questions, most notably concerning the authors’ roots, their particular writing process, their literary inspirations, their publishing experience, and how their stories originate and develop. In their various responses the writers supply a hearty helping of wisdom and wit, offering encouragement, sage advice, and valuable insight into history as well as their own craft. Here is a sampling:

- Shuly Cawood: [T]he main thing is being dogged about one’s writing, not giving up. This writing stuff takes grit, and rejection is all around for the taking.

- Robert P. Waxler: Like No-Fly Zones, there should be no-Wi-Fi Zones, countercultural spaces where literature and language help to maintain the traditional sense of what it means to live a good life and to preserve our humanity.

- Lorna Hollifield: Especially in the South, we seem to be so connected to the places we ran around barefoot as a child.

- Lindsay Parnell: [T]he South breeds sin, storytellers, and contradiction.

- Coleman Hutchison: I kept thinking how much we lose when we only tell the winner’s story, when we dismiss any part of a rich and vexed literary history.

- M. Maitland Deland: I love writing, so I make the time for it, even if that means getting up earlier or going to bed later on certain days.

- David Bradley: First lesson: sit alone in a room for a day and don’t talk to anybody except yourself and people you are making up. Second lesson: Repeat. Third lesson: After five days, ask yourself if you’re eager for day six.

- Emily Carpenter: I wholeheartedly endorse the Southern Gothic label … I’d really hoped for that delicious moss-draped, muddy, “there’s-something-off-about-this-place” feel you get in the best Southern Gothic books.

- Glenn Arbery: I’ve never felt myself to be a scholar … My sympathies have always been with Montaigne in this regard: I love to read, and my reading tends to follow my interests, and my interests have never been specialized.

The general consensus is that writing is hard and that there is no teacher quite like experience. This repeated sentiment reminds Mendenhall of Hemingway: “There is nothing to writing. All you do is sit down at a typewriter and bleed.” Notwithstanding technological shifts in the tools, Hemingway seems to get it just about right. But along with the blood is a passion and driving desire to create, to explain, to grapple with the past, to come to an ever more complete understanding of one’s own self and the world around them. For Southern writers, this grappling and wrestling with the past is powerful, especially when it comes to slavery and race relations.

Arbery describes slavery as a “kind of original curse that we’ve had to work out in our national history, and the effects of it, because of its visible heritage, will not go away in our lifetime and perhaps not in the lifetimes of our great-grandchildren.” For Arbery, it is an “intractable problem” that is continually being worked out in literature, including his own. David Bradley is unapologetic for his decision to write about the complex and dark history of race relations in America. “I do think it’s important,” he tells Mendenhall, “that fiction that deals with ‘controversial’ aspects of American history be able to withstand a certain kind of scrutiny, because there are so many Americans determined to disbelieve. But facts are hard to dismiss.” For perspective, Bradley wrote of a lynching of a black man that was attended by five thousand spectators, an enormity some may still find hard to fathom actually occurred.

A topic Mendenhall engages with Robert Waxler is the dominant place digital media has assumed in today’s culture. Waxler elucidates the problem: “screen culture has become the mainstream culture, favoring the visual over the textual, privileging images over words … Quick absorption of information rather than slow and thoughtful processing is typical of the current behavior.” Succumbing to the glitter of every new technological advance, people are losing touch with what really matters. But “Books make us human,” Waxler asserts.

When asked about their literary mentors and guides these writers answer, almost resoundingly, in one voice. William Faulkner, Flannery O’Connor, and Walker Percy have indeed set the bar high for veteran and novice Southern writers. Mendenhall is not reluctant to draw comparisons to these titans when warranted, eliciting responses of genuine surprise and humble gratitude.

Allen Mendenhall’s Writers on Writing is an illuminating and pleasant read for those familiar with the Southern literary tradition as well as those coming upon it for the first time. There is, quite honestly, something for everyone. As Robert West invites the reader in the introduction, “Come listen to the conversation; you’ll make many happy discoveries.”

Elizabeth Bittner holds a B.A. in Political Science from The Thomas More College of Liberal Arts and a Masters degree in the Humanities from the University of Dallas. She currently resides with her husband and daughter in rural Missouri.