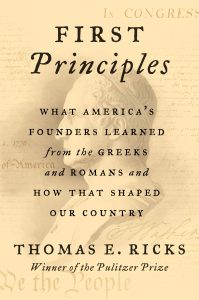

by Thomas E. Ricks.

Harper, 2020.

Hardcover, 416 pages, $30.

Reviewed by Casey Chalk

A classic, said Mark Twain, is “a book which people praise but don’t read.” One would certainly say that about classical literature and philosophy—though once widely assigned across American colleges and universities, few Americans have read Homer’s Iliad or Virgil’s Aeneid. Much the same can be said about Greek and Latin, languages once required to graduate from many academic institutions (Yale maintained a requirement for a basic Latin examination until 1931); or Plato and Aristotle, whose writings were once considered an essential component of acquiring a Western education. Not so the American Founders, argues Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Thomas E. Ricks in his book First Principles: What America’s Founders Learned from the Greeks and Romans and How That Shaped Our Country.

“The classical world was far closer to the makers of the American Revolution and the founders of the United States than it is to us,” argues Ricks. He notes, among many examples, that the Senate, the Capitol, and the names of our two major parties all have an ancient origin. The federal buildings in Washington, D.C. are classical in style, as are the monuments to Jefferson and Lincoln, among others. Our coinage features Latin phrases like e pluribus unum. Even many early American settlements—Ricks notes that upstate New York alone features Troy, Utica, Rome, Syracuse, Ithaca, Cicero, Hector, Ovid, Solon, Scipio Center, Cincinnatus, Camiullus, Romulus, and Marcellus—honor the Greeks and Romans.

Ricks’s overarching thesis is that classical philosophy and literature were far more influential on the Revolutionary generation than was English Enlightenment philosopher John Locke. These sources included, among others, the Iliad, Plutarch’s Lives, Xenophon, Epicurus, Aristotle, Cato, and Cicero. A corollary to Ricks’s argument is his assessment that the first four presidents viewed themselves not only as political inheritors of the Greeks and Romans, but even sought to cast themselves as personifying afresh particular classical heroes.

Part of the reason for the American appreciation for the ancients had to do with the influence of Scottish immigrants. Both Jefferson and Madison, for example, were trained by Scottish tutors. Madison also studied under Scottish clergyman John Witherspoon at Princeton. These Scotsmen drank deeply of the Scottish Enlightenment, which was defined not only by intellectual dynamism and skepticism, but a love for the classics. This intellectual affection favored Rome over Greece, and especially the late Roman Republic in the first century B.C.

George Washington, though the least educated of the first four presidents, was a great admirer of the ancients. His favorite play, for example, was an eighteenth-century English tragedy about the first-century Roman statesman Cato. The Romans described Cato as the very embodiment of virtue, rejecting corruption and luxury in favor of humility and simplicity, even despite his wealth. Cato was also a firm resistor of the grasping, imperialistic tendencies of Caesar—indeed, he even committed suicide rather than submit to Caesar’s armies. Washington’s legendary stoicism and virtue seem intentionally cut from the same cloth as Cato.

It was not only Cato whom Washington emulated. During the Revolutionary War, the general maintained the strategy of Roman tactician Fabius, who defeated the great Carthaginian general Hannibal by avoiding direct military confrontation against a larger foe in favor of small engagements and targeting supply lines. Indeed, multiple colleagues such as Major General John Sullivan, Major General Arthur St. Clair, and Marquis de Lafayette exhorted Washington to pursue Fabius’s approach. Again, at war’s end, Washington played the role of Cincinnatus, the Roman leader who was given temporary dictatorial control over Rome to defeat an invading army, which he did, and then promptly returned to private life.

John Adams, in turn, sought to embody the best qualities of the Roman orator Cicero, whose success in defeating the Catiline conspiracy to overthrow the Roman Republic was, says Ricks, “the dominant political narrative of colonial American elites.” Cicero came from humble origins, though he applied his famous intellectual acumen to Roman law, rhetoric, and politics, becoming one of Rome’s two consuls in 63 B.C. It was also in that year that he gave his four famous orations against the seditious soldier and patrician Catiline. Those speeches were favorites of Adams, who read them aloud to himself at night. Like Cicero, Adams was not a man of wealth, noble birth, or military glory. Also like Cicero, he was self-made and used his intellect, seemingly limitless energy, and success as a lawyer and rhetorician to gain political power.

As for Thomas Jefferson, Epicureanism was the Greek philosophical tradition that was closest to his heart. While Washington was a stoic, Jefferson was romantic, passionate, aesthetic, and self-indulgent. The Virginia planter and statesman read entire volumes on Epicurus, and wrote to his former private secretary William Short: “I too am an Epicurean.” What Epicureanism meant, he told the Italian-English artist Maria Cosway, was that, “The art of life is the art of avoiding pain … The most effectual means of being secure against pain is to retire within ourselves, and to suffice for our own happiness.”

Ricks argues that Jefferson’s Epicurean predilections are visible even in the Declaration of Independence, particularly in his choice to replace John Locke’s “property” in the document’s legendary line about “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” His aestheticism is also on display in the design of the new city of Washington, D.C.—he required that the bricks used to build the Capitol follow ancient Roman proportions!

The influence of the ancients is also visible in the Founders’ interest in the Amphictyonic League, a confederation of Greek city-states that had equal voting rights regardless of their size or power. Many of the Revolutionary generation cited its council structure as necessary to ensure the protection of smaller colonies. Though the reference to us is obscure, we see its legacy in our Senate, which has equal representation for all states. Madison, notably, was less amenable to this reference, arguing in his Federalist 18 that the structure of the Amphictyonic Council allowed the strongest cities to awe and corrupt the weaker states.

Another Greco-Roman concept central to the revolutionary generation was virtue, “the essential element of public life.” The word appears constantly in the collected correspondence of the Revolutionary generation, more even than the word “freedom.” “Virtue or morality,” declared George Washington, “is a necessary spring of popular government.” Another Virginian president, James Madison, similarly asserted: “To suppose that any form of government will secure liberty or happiness without any virtue in the people, is a chimerical [imaginary] idea.” For the Founders, says Ricks, virtue was not singularly religious, but meant “putting the common good before one’s own interests.”

Yet virtue, Ricks claims, ultimately let the Founders down, because they naively believed that it would act as a restraining force in politics. Political parties, which they viewed as “unnatural and abhorrent” and antithetical to virtue, came to dominate the political landscape. Moreover, for all their talk of virtue, the Founders accepted a particularly brutal form of human bondage as a natural part of the social order. Indeed, Southerners cited the example of both the Greeks and Romans to defend their own form of racial chattel slavery—although the Roman slave revolt of Spartacus is noticeably absent from the writings of the slaveholding Virginia political class.

In the nineteenth century, classicism became less central to American self-identity, and was even ridiculed by the nation’s most prominent voices. Ralph Waldo Emerson in 1844 labeled the collegiate study of Latin and Greek to be “warfare against common sense.” One of the reasons for this turn away from the ancients was industrialization, which led the academy to focus preeminently on practical skills and sciences that would further economic growth. Ricks also blames American individualism, evinced in evangelicalism and other religious movements like Mormons and millennialists. Perhaps, though, one might more broadly blame the Protestant Reformation and the Enlightenment, both of which were suspicious of the inherited wisdom of the ancients, especially Aristotle and his medieval interpreters.

Ricks offers ten steps he believes will restore America to the original vision of the Revolutionary generation. Some are a bit overwrought—the first, “Don’t panic,” is an exhortation to avoid anxiety over Trump’s presidency and perhaps also its legacy. Others, like renewing a public understanding of the common good or prioritizing freedoms of conscience, assembly, and speech, are indeed essential. It was refreshing here to read Ricks rebuke American universities for their kowtowing to activist students incapable of listening to people with opinions different than theirs.

Though Ricks charges the Founders with naivete, he is perhaps just as guilty of it. He urges Americans to “promote, cultivate, and reward virtue in public life—but don’t count on it,” meaning citizens should practice virtue in a manner more akin to how the Founders understood the term, but not necessarily expect it from their fellow citizens. Yet volunteerism—a good indicator of civic participation—is on the decline, especially among the American youth. Faith-based organizations that provide innumerable services to Americans are dying. Religious impulses have always loomed large in the background of American public service, and it seems unlikely generic, secular exhortations to “do good” will present an adequate replacement.

Ricks calls on Americans to “rehabilitate ‘happiness,’” by appreciating “the Enlightenment’s broader, richer notion of happiness,” defined by humility and gratitude. Yet it is not the Enlightenment that originated this idea, but the ancients and their Christian interpreters. Aristotle in his Nicomachean Ethics refers to eudaimonia, the highest human good, and the only human good that is desirable for its own sake. Christian thinkers like Thomas Aquinas identified this highest good as God, experienced through human contemplation manifested in activities like meditation, prayer, and worship. It is doubtful that secularism, so beholden to a global market economy that instrumentalizes everything and indulges our most base desires, has the moral energy or imagination to restore what has been lost. We are living in a world that is, in the words of the great philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre, “after virtue.”

First Principles is an engaging analysis of America’s founding, understood through the lens of an ancient world that is increasingly distant and obscure to us in the twenty-first century. If we were to once more carefully and critically look to the classical world to answer our most pressing contemporary political challenges, we would find both guidance and instructive warnings. Nevertheless, untethered as we increasingly are from religious truth and faith-based institutions capable of holding the ancients accountable to an objective, metaphysical reality—the most essential of principles—Ricks’s recommendations seem insufficient for the dilemmas of our day.

Casey Chalk is a columnist for New Oxford Review and Crisis Magazine. He has degrees in history and teaching from the University of Virginia and a masters in theology from Christendom College.