Classic Kirk:

Classic Kirk:

a curated selection of Russell Kirk’s perennial essays

A Note from the Editor

In his memoirs, The Sword of Imagination, Russell Kirk described meeting Flannery O’Connor at the home of mutual friends and hearing her read aloud her short story, “A Good Man Is Hard to Find.” Writing in the third person, he recounts that the “impression that she made upon Kirk by her presence was as strong as that created by her stories…” He soon came to admire her high literary talents.

For her part, O’Connor gave a humorous description of her first impression of Kirk, as related in his piece. She read Kirk’s works closely and discussed them with her correspondents, and later reviewed his books.

Flannery O’Connor: Notes by Humpty Dumpty

From The Sword of Imagination: Memoirs of a Half-Century of Literary Conflict (Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1995)

At the house then called Cold Chimneys, in Smyrna, Tennessee, where Brainard and Fanny Cheney lived, Flannery O’Connor and Kirk met—for the first time and the last, here below. This occurred in October 1955; in Kirk’s fancy, the occasion does not seem so far distant in time. For a conscience spoke to a conscience then, and the soul of Flannery O’Connor endures.

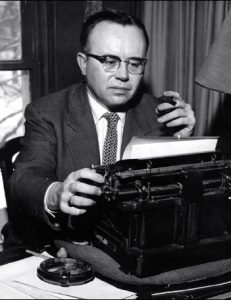

She happened to greet Kirk in the broad entrance hall of the handsome old house, which had been built by a Carpetbagger. Kirk had not known that she too would be staying there, and he had read nothing of hers. As she says in her published letters, The Habit of Being, she and Kirk were shy with each other. Probably she had not expected the portentous author of The Conservative Mind (as Eliot puts it, “the mild-mannered man entrenched behind his typewriter”) to look like “Humpty Dumpty (intact) with constant cigar and (outside) porkpie hat” (Flannery’s description of Kirk). For Kirk’s part, noticing her crutch and a bandaged leg, and knowing nothing of the disease that had fixed upon her, he inquired whether she had broken that leg; she said no, but did not explain.

Kirk’s first acquaintance with her power of imagination came that evening or the next, when she read aloud “A Good Man Is Hard to Find.” She mentioned that a young man in Los Angeles had asked for permission to adapt the story for a film, he being a doctoral candidate in theater arts; he had chosen “A Good Man” because “it would be cheap” to produce.

“Cheap and nasty,” Kirk offered. She smiled. Flannery went on to tell how she had named The Misfit in her story after a real escaped criminal by that appellation who had popped up in the Georgia papers. Kirk drew parallels from Michigan experiences. As Flannery mentions in a letter, she and Kirk were better at talking in the company of the Cheneys and of fellow guests than when left alone in a parlor. Kirk regretted that he had not told tales of his Scottish wanderings afoot, which might have amused and interested her.

Probably she was interested in Kirk because, as an informed Catholic, she had read his essays in Commonweal, America, The Month, The Dublin Review, and other Catholic periodicals—though Kirk still was unbaptized in any church. Then, too, “Lon” Cheney, their host, had reviewed The Conservative Mind sympathetically in Sewanee Review. She herself was to review Kirk’s Beyond the Dreams of Avarice, published in 1956. Long after Flannery’s death, Kirk would be shown her library books, desk, chair, and all plenishings—preserved in the library of Georgia College at her town of Milledgeville; and there he would find a copy of The Conservative Mind, with her marginalia.

There was much they should have talked about during that weekend with the Cheneys. They seemed to agree on everything—she from the Milledgeville farm, he from the old judge’s house at Mecosta. Although Kirk’s junior in years, she was in advance of him; when Flannery died in 1964, Kirk—then forty-five years old— had begun to apprehend truths that Miss O’Connor had discerned at the age of thirty. It turned out that she had read Kirk’s Program for Conservatives and his Academic Freedom. Of Kirk’s Works, she wrote later that “Dr. Johnson would almost certainly admire them, both for their thought and the vigor with which it is expressed.” That approbation was heartening in a bent world.

In her letters she refers to the title of a magazine Kirk then was intending to found, The Conservative Review; she begins to doubt whether the review will take on flesh. It did, eventually, but under another title, Modern Age—a quarterly still published. As matters worked out, the first number of the review appeared too late for the publication of an essay by Donald Davison and an article about Flannery O’Connor by Ashley Brown, which Kirk meant to print. He never had occasion to write anything about Flannery but two or three syndicated newspaper columns, an unsatisfactory mode for discussing so complex and subtle a writer.

The impression that she made upon Kirk by her presence was as strong as that created by her stories, which Kirk began to read on his way back from Tennessee to Michigan. Having acquainted himself with nearly everything that she had written, he wrote to T. S. Eliot— then his London publisher—that he really ought to read her, if he hadn’t already. (There was little among new fiction that Kirk commended to Eliot.) He replied, in February 1957, that he had seen a book of her stories when he had been in New York, “and was quite horrified by those I read. She has certainly an uncanny talent of high order but my nerves are just not strong enough to take much of a disturbance.”

He would have admired Flannery O’ Connor as he admired Simone Weil, and for much the same reasons, had he penetrated below the surface of Flannery’s stories to the power of her moral imagination, growing from a faith like Eliot’s. But that did not come to pass. “Similarly with another book shown me in New York,” Eliot went on in the same letter to Kirk, “a novel by Nelson Algren; that is terrifying too and I do not like being terrified. Apart from the general aversion to prose fiction which I share with Paul Valery, I like pleasant, sunny comedies such as I write myself.”

Eliot was unaware that a gulf was fixed between Nelson Algren (whose name he garbled in the letter) and Flannery O’Connor: the gulf between the diabolic imagination and the moral imagination, a subject discussed by Eliot himself in After Strange Gods. As for Eliot, so for Flannery, “the reverence and the gaiety” were not “forgotten in later experience”; no, not in “bored habituation,” or fatigue or tedium, or “the awareness of death, the consciousness of failure….”

Had TSE summoned up courage sufficient to read Flannery through, he would have discovered her similarities to Nathaniel Hawthorne, one of the few major American authors Eliot admired. For what fascinated Flannery was sin—and redemption. As Pope John Paul II wrote very recently, without an understanding of the nature of sin it is not possible to form a conscience—or to become fully human. That is the teaching of The Marble Faun, The Blithedale Romance, The Scarlet Letter; it is the teaching of Flannery O’Connor through “Southern Gothic.” Kirk well understood her fantastic and her depraved characters, their twisted faith and all, because precisely such people lived about him in Mecosta County; they emerged repeatedly in his own stories, many of those written long before he met Miss O’Connor, and which presumably she never saw. His “Off the Sand Road” might have come from Flannery’s typewriter; so too, except for their revenants, his “Behind the Stumps” and his later “There’s a Long, Long Trail a-Winding” and “Fate’s Purse.”

So far as Flannery professed politics, she stood with the Agrarians—adding a Catholic element. “It is…a rethinking in the obedience to divine truth which must be the mainspring of any enlightened social thought,” she wrote in her review of Beyond the Dreams of Avarice, “whether it tends to be liberal or conservative. Since the Enlightenment, liberalism in its extreme forms has not accepted divine truth, and the conservatism which has enjoyed any popularity has shown no tendency to rethink human truths or to reexamine human society.” But Kirk had done both those things, she added, making “the voice of an intelligent and vigorous conservative thought respected in this country.” That review was not called to Kirk’s attention until Flannery had been dead for twenty years.

Kirk felt so swiftly drawn to only one other writer that he met—George Scott-Moncrieff, so like Flannery in character and conviction. In sorrow, Flannery told Kirk how the bishop of Savannah had demolished, next to the cathedral, one of Savannah’s finest old houses, to clear the ground for a thoroughly hideous school (now disused but unhappily still standing). George Scott-Moncrief, quite as Catholic as Flannery and as much a cherisher of the historic past and its monuments, would have expressed himself on such a melancholy subject in similar wry phrases. Neither of those two ever read the other, more’s the pity.

It might please and amuse Flannery O’Connor to read these paragraphs, so tardily written. Yet she must have surmised, with her quick charitable insights, that the taciturn Humpty Dumpty esteemed her. Beyond time, we two, who met but once, may be enfolded in the community of souls.

© The Russell Kirk Legacy, LLC

Classic Kirk:

Classic Kirk: