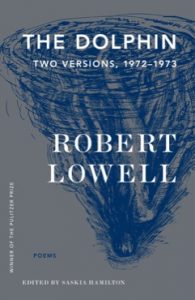

by Robert Lowell,

edited by Saskia Hamilton.

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2019,

Paperback, ix + 195 pages, $18.

The Dolphin Letters, 1970–1979:

Elizabeth Hardwick, Robert Lowell, and Their Circle

edited by Saskia Hamilton.

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2019,

Hardcover, vii + 504 pages, $50.

Reviewed by Eugene Schlanger

In the age of Donald Trump, self-absorption is the norm. Equally, in contemporary American poetry, the re-publication of The Dolphin, a 1973 volume of poetry by Robert Lowell, America’s most accomplished mid-twentieth-century poet, demonstrates that poets also let go of their experiences only with great difficulty.

The distinguished literary publishing house Farrar, Straus and Giroux has published The Dolphin again. A quick glance at the 104 poems in this volume easily reconfirms Lowell’s great felicity and facility with words. And, as quickly, this book also demonstrates that much of the American poetry that has been published since 1973 is minimally competent and mostly uninteresting, despite the annual fanfare to the contrary.

A literate cynic might suggest that the ghosts of great publishers of the past, like Lowell’s publisher Robert Giroux, have now come back to haunt their successors, but that implies that today’s mendacity and mediocrity is a permanent feature of the literary landscape. Most of what is published always sinks to the bottom but there will always be new, interesting voices pushing their way to the surface. And new, insightful critics to replace the sycophants.

Despite the power and eloquence of Lowell’s earlier poetry, what we are presented with in this, his penultimate book, is well-expressed private anguish and, consequently, a lot of gossip. Lowell was always a confessional poet, though his work transcended personal angst. But, in this self-important age, praise is now lavished upon the poet at annual creative writing awards ceremonies, instead of upon the poetry. We no longer first read the words. Readers are now told about the lives of the poets—their political beliefs, ancestries, and sexual orientations—in order to appreciate a poem. Personal context is content, but Lowell’s reach and his scope were always stronger and farther than that.

Some may suggest that the best poetry, especially lyrical poetry, has always followed this personal course. Don Chiasson has suggested, in his review of a book-length study of Thomas Wyatt’s small poem, They Flee From Me, that we may just utter poems in order to seduce others or to share our loss when we fail.

Sadly, a reading of The Dolphin (both the final published version and the edited typescript) mostly exudes anguish, and there comes a point when even the most well-wrought repetitive sadness just dulls the senses. One wonders why anyone would want to follow this poet through one skilled yet self-torturous poem after another. There are better odysseys than this book.

Apparently, even the white male descendants of New England Brahmin are an unhappy lot. But poetry is not Facebook, texting, or emoji.

A better editor might have remonstrated with Lowell during his lifetime, and now his children who control his literary estate, that at some point a poet must accept that his life’s studies are only one marker in a vast sea of declamations. The references to New York and London in the last century, to historical persons and events, to other writers, and to family, only conjures up one time and place. The next step in meaningful art, including poetry, is to bridge the gap between the immediate poet (mad with his own observations) and the reader living anywhere else, including Mumbai or Tehran.

The existential question is whether this book would exist without any knowledge of Lowell’s life.

Does the poet’s personal existence, however sad or seething at times, add literary value or coherence?

Or is his skill just practice, practice, practice?

And, without getting off the couch, does anyone now really care about this American poet’s past, except writers in Brooklyn trying to understand the hatred of poetry?

The confessional form may sell more poetry and be easier to market in this age of trumpeted self-absorption. Yet, how less powerful does all this selfhood and self-revelation now sometimes seem? How less clever than those many sudden images on asocial media?

It is doubtful that this will even be cocktail-hour throwaways, once we can again gather in groups larger than ten. And these poems certainly will not help you seduce anyone. On the contrary, unless misery is your way of coping with the world’s regimes, you might consider this small volume as a notepaper substitute. And Lowell might have smiled appreciably at that because his poetry, when first published, was innovative. He should have stopped and left the reader craving more. There are far more elegant shouts and cries for love in literature, and in the world’s public lexicon, than The Dolphin in whole or in part.

Autobiography is of great value to anthropologists who pour though an era’s leftovers for the objects of everyday interest. But here, Lowell’s staccato sequences seem so desolate and desperate. Perhaps they are emblematic and typical of those always upset New York intellectuals of the last century. On the other hand, after this book, I appreciated more a remark by the poet Richard Howard who once told me that he intended to destroy all drafts of his poetry.

Of course, Lowell is not completely at fault. Go back to his earlier books, Life Studies and For the Union Dead, and you will find one of the most creative writers of the second half of the twentieth century, and someone who knew how to flourish his pen. But here Lowell (like so many other poets who won’t stop writing) has proven that all artistic endeavors have limits. Should critics and poetry readers relegate poets to their graves, and then display only their best books or poems? Probably. Constant cries of greatness diminish real excellence, and fame (as everyone knows) sometimes laughs in our faces.

I am not suggesting that this book should have been suppressed. There is a place even for last lusts and emotions. The great German polymath Johann Wolfgang von Goethe embarrassed himself very grandly in his mid-70s, after a teenager said no to his marriage proposal, and he wrote an elegy now not worth reading.

Ultimately, The Dolphin is episodic, like a soap opera where you can pick up the same storyline six months later. It distracts and, like much contemporary American poetry, it relies upon an accumulation of disjointed words or sounds, rather than any sustained and expressive lyrical flight. Sometimes this book is simple, sometimes funny, and sometimes silly like Keith Haring’s art. Most of the time it is obtuse. If your heart throbs because you are in love, or lonely, there are better wordsmiths, and better painters too. Just don’t tell the universities or galleries that are dependent upon their collections of mid- to late-twentieth-century bric-a-brac.

Lowell did too much here. These poems are so full of hard-striving phrases that so forcefully leap off the page that one is left with a hodgepodge of images and sounds, not a lovely or orderly cascade. And that impression is compounded because Lowell’s mind is all over the place. He reminds me of Picasso and all those portraits of all those women he produced en masse, a legacy not of greatness but of commonality and decreasing artistic interest. This is verbal showoff.

In the end I preferred rambling through the letters much more than these poems. Hardwick, as she meanders through the events of their life, is so much more interesting and pleasant to read. She comes across as the more humane writer. Her expressive letters are more meaningful, and accessible, than the simultaneous shouts of a distraught exaggerating poet.

Eugene Schlanger, the Wall Street Poet, is the author of September 11 Wall Street Sonnets, which will be reissued upon the twentieth anniversary of the terrorist attacks.

Support The University Bookman

The Bookman is provided free of charge and without ads to all readers. Would you please consider supporting the work of the Bookman with a gift of $5? Contributions of any amount are needed and appreciated!