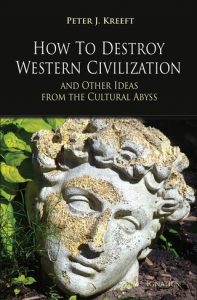

by Peter Kreeft.

Ignatius Press, 2021.

Paperback, 182 pages, $17.95.

Reviewed by Robert Grant Price.

One caricature of a conservative is a man (always old, always white) shouting at clouds. “Society is going to hell!” he tells vapour.

Given the last two years, maybe that old man is right.

For the moment, as the world climbs out of the rut brought by lockdowns, society looks like the contents of a demolished house pouring out the back of a garbage truck. Across the Western world, pandemic-weary citizens are witnessing a system collapse playing out in real time and in real life. Skyrocketing inflation; rising crime rates; an epidemic of mental illness; the politicization of art, education, and medicine; nuclear brinkmanship; supply chain chaos; bio-fascism; a profound distrust of government, news media, and universities; not to mention a deepening divide between those who wear masks and those who do not (itself shorthand for the hyper-partisanship seen in nearly every other realm of life)… these all seem like evidence of a civilization folding into the abyss.

No, things are not good. No, this is not fun. But Peter Kreet is fun, and the witty, pithy observations packed into How to Destroy Western Civilization and Other Ideas from The Cultural Abyss, a slim collection of 18 short essays, showcase Kreeft’s lucid style of philosophy—a style that makes readers wonder how they ever took anything so seriously. Laugh, it will be alright. Or it may not be. But there is humor in everything, right?

Conservatives, culture warriors, and assorted doomsters will recognize in How to Destroy Western Civilization arguments common to the End-is-Nigh genre. The argument goes something like so: If you tell off your father (forsake tradition), eat nothing but candy (gorge on the riches provided by your father’s traditions), and castrate yourself (cut off your testicles), do not be surprised when you find yourself at the end of history corpulent, alone, and desperately unsatisfied.

Provocation is not the point of this book—notwithstanding the juiciness of the book’s title. Getting a laugh at the expense of liberals is. On page after page, Kreeft pulls wedgies on the transgressives, relativists, and atheists who more than anybody today steer the soap box race car called liberalism. In tit-for-tat fashion, Kreeft caricatures these people in the same way they mock scream-at-the-clouds conservatives. This species of liberal loosens the bolts on his soap box car and barrels down a rocky incline. Never one to let logic get in the way of a bit more liberation—or brakes to slow him down—he goes faster.

“Society is going to hell!” he cheers.

Kreeft, a professor of philosophy at Boston College and author of innumerable books, including a fascinating and peculiar study of dying, Love Is Stronger Than Death, spends several essays parsing and pulling at what is going wrong with society. He lays most of the problems at the feet of liberalism, a term he admits to finding confusing. “I used to call myself a liberal, back in the sixties,” he writes in the essay “What Is a Liberal?” “I now call myself a conservative. But I haven’t changed my mind on a single issue. The labels have changed.” It is a sentiment shared by many confused and disaffected liberals, most recently Elon Musk who tweeted that it was not he who moved right, it was the ground under him that moved left.

In several essays, including “The Logic of Liberalism,” a chapter composed entirely of aphorisms, Kreeft works up a portrait of the liberal as a person who confuses permissiveness with compassion and intolerance with tolerance. “Discriminating people don’t discriminate,” he mouths liberals saying in one of his many one-liners. Kreeft, now in his mid-80s, knows how to write for Instagram: “The Hell with Hell. People who believe in damnation should be damned. The idea that some ideas are damnable is a damnable idea.” “Everyone is prejudiced except us.” “Conform to nonconformity.” It goes on like this for pages.

Humour does not undermine the seriousness of Kreeft’s examination of how a culture collapses. In his roundabout way, Kreeft eventually arrives at sharp, salient points that show the ruptures in society. In one take it or leave it moment, Kreeft writes: “A world without objective moral values, without the natural law, is a world without heroes. Only an objective morality, not a subjective morality, can be the frame around the picture of the plot of a life.” Liberals, or the people who call themselves liberals today, will object. “But whose objective morality?” they ask rhetorically, “and who gets to choose?” These are fine questions, but they only delay the answer that Kreeft spends much of his time in this book underlining. If there is no objective morality, then anything goes. If anything goes, all arguments lose their point. Heroism loses all definition. (“If there is a Heaven and a Hell, life is a battlefield. If not, life is a hot tub. There are no heroes in hot tubs.”) Thought, however clever, darkens since in the end there is nothing to illuminate. Society grows stupid in scared silence. That is the horror that Kreeft, like a fat, laughing Buddha, sees in our future.

The book closes with several essays punching at the themes Kreeft presents in this book (and in others of his books). The Catholic philosopher tosses around the idea of freedom and the intendent confusions about freedom that circulate in a confused culture; chastises life-long agnostics as amoral for never drawing a conclusion about God’s existence; praises Islam’s “primitive” (not a bad word as Kreeft sees it) impulse to worship; distinguishes between pity and pacifism; and concludes the book with an eighteenth essay containing 18 judgements about judgement. This last essay closes the book in a fine fashion by drawing a bead on contemporary culture’s problems: Successful cultures judge wisely while dying cultures forget how to formulate a judgement, lose confidence in the judgements they make, and resort to the dead-end position that judgement itself must be the problem, so toss it.

Kreeft’s wandering, aphoristic mind can frustrate, at times. It is like being stuck on an island and seeing a book wash up on the beach. Suicidally bored, you grab the sopping mess, dry the pages in the sun, and peel apart the wrinkled leaves to find nothing but koans and haikus. It’s great…for a while. Incredibly insightful. Wise. I mean, how could you complain? But after a couple dozen pages of lucid yet fragmentary wonderings, you start craving a prolonged study of something. Of anything. Water…I need water.

For refreshment, Kreeft delivers a history of symbolic logic. It helps to quench the thirst. It focuses the mind. Kreeft uses this unlikely history to explain one of the ways Western culture went wrong. Symbolic logic, “a mathematical logic, a logic of quantity,” washed through philosophy departments around the time when Kreeft began his career as a philosophy professor in the 1960s. He saw his fellow professors ditch the Aristotelianism of earlier generations for the shiny new field of symbolic logic. Confusion followed. “Symbolic logic has no way of knowing and prevents us from saying what anything is!” he explains. By stripping words of meaning and thinking digitally about life rather than pondering the living world, symbolic logic salted the fields of philosophy. We flip stones to find worms to eat. “Language is the house of thought, and homelessness is as life-threatening for thoughts as it is for people. If we should begin to speak and think only in nominalistic terms, that would be a monumental historic change. It would be the reversal of the evolutionary event by which man rose above the animal in gaining the ability to know abstract universals. It would be the mental equivalent of going naked on all fours, living in trees, and eating bugs and bananas.”

How to Destroy Western Civilization and Other Ideas from The Cultural Abyss rests on the Aristotelianism and Christian roots that logicians believe they have so wisely outflanked and uprooted. This fact makes How to Destroy Western Civilization a book that will appeal both to old-fashioned conservatives shouting at the clouds and the new-fangled counterculture needing a game plan—and a joke book—for its rebellion.

Robert Grant Price lectures at the University of Toronto Mississauga.

Support the University Bookman

The Bookman is provided free of charge and without ads to all readers. Would you please consider supporting the work of the Bookman with a gift of $5? Contributions of any amount are needed and appreciated!