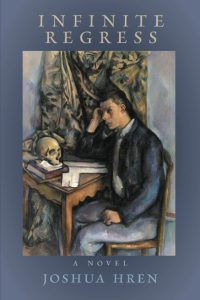

by Joshua Hren.

Angelico Press, 2022.

Paperback, 296 pages, $19.95.

Reviewed by David G. Bonagura, Jr.

“What he taught me was literally revolutionary in a way that set me free from the last hang-ups of that pablum Mom fed us and wanted us to nurse on into infinity.” The “pablum” is the sincere Catholicism of the late Catherine Yourrick. The “he” is Professor Theo Hape, a defrocked priest whose name, reminiscent of “God Hate,” points to his role in Joshua Hren’s polyphonic novel. Infinite Regress penetrates beyond the perils of socially depressed middle-America—“the staggering skyscrapers of debt that two of the last three presidents called ‘pandemics,’ crises as worthy of intervention as the drugs dragging like a net across the nation”—into the underlying causes of one family’s malaise. These causes are not, at root, economic, but existential—they stem from fumbling with the mysteries of God, evil, sin, and human nature.

The novel’s co-protagonist, Catherine’s son Blake, first met Hape at the university in Milwaukee, where the ex-Jesuit taught the course “Introduction to Theoretical Notions About What We Happen to Call God.” The aging Hape, who sports a collection of rock-n-roll t-shirts to wear with his blue jeans in the classroom and at Milwaukee’s bars (Arius’ Arse is his favorite dive), takes a perverse interest in Blake. He then offers the young graduate, who is running from collectors seeking repayment of his $50,000 college loan, a twisted offer: Hape will pay Blake’s loan in exchange for a night together. With the Yourrick family home the collateral for the loan, Blake’s bachelor’s degree in “Theory” imminently threatens his parents and siblings’ existence. He weighs what he should do, seeking the advice of two less than trustworthy souls: his older brother Max, a psychologist, and his “uncle” Rick, a neighborhood collector for a wealthy widow.

For his part, Hape uses the stage at Arius’ Arse to present a new theology to influence Blake. He tells his misfit audience that they are wrong that Christianity is on its way out. Since “it speaks to our deepest delusions, our most pathetic ‘needs,” it will endure, “so we need to rewrite the terms of the debate.” Most in need of reinterpretation is our theology of Satan, whom Hape wants to reestablish, not forget, so we can have someone to blame other than ourselves. Later, Hape declares that “anything can be committed without any moral qualms whatsoever so long as the Individuals committing it Consent.”

As Blake deliberates over his professor’s offer, the other protagonist, his father Garrett, also a former student of Hape, steps drunkenly to the fore. Whereas Blake represents the searching, unattached Millennial generation, Garrett, the son of hypocritical believers of the Greatest Generation, represents the skepticism of Generation X. Garrett moved his family so he could work in a Botox factory while completing his doctorate in philosophy at Thinkery University. After four years, he quit the program since neither he nor any professor can “answer the fundamental question: why is there something rather than nothing? … Philosophy is not two classes per semester and two peer-reviewed articles published in Hairsplitting every two years.” The professors offer only “an unparalleled hatred of thinking” to go along with their “scoff” at the regular citizen.

Garrett returns to Milwaukee with his family, where his alcoholism and atheism tear apart his marriage to the devout and the terminally ill Catherine. As the novel unfolds, we regress deeper into Garrett’s past, as the unveiling of several surprises that contributed to his malformation portray him as a deeply pitiable figure. As he recalls each event, Garrett slumps deeper into his own misery. After Catherine’s death, he finds a letter in which she lamented he “poisoned our family.” Their son Max thinks the widower Garrett is “so defeated”; he cannot handle “bearing too much reality.”

Garrett and Blake’s difficulties represent two paths trodden by those who have given up on God and have been left behind by the twenty-first-century economy. Max, the eldest of the three Yourrick children, represents a third: the disengaged and loveless professional. Max “consciously sought out a woman much colder, more intellectual, more secular” than his devout mother, and found her in Haimavati, whose name in Hindu signifies the female principle of the divine (many of the novel’s characters have names worth pondering). Haimavati, having married Max, became the hypocritical author of Myths of Monomania: Monogamy as Pathology. Never believing that “such brute facts as pregnancy simply could touch her ‘like a colonizer,’” she ends up pregnant with twins, whom Max labors to support as a less than self-assured shrink.

Hren’s portrayal of their listless marriage and Max’s professional career are shining examples of the novel’s most canny feature: penetratingly funny satires of the shallowness of contemporary American life. When Blake barges into Max’s office to discuss Hape’s offer, he throws himself on the couch declaring, “I have a bad case of gender discombobulation!” When Max corrected him, Blake replied, “Euthanizer euphoria? Once, when I was a child…I stole the baby’s doll and ran upstairs and pretended to nurse the thing! What started out with a fit of jealousy finished in the happiest day of my life!”

Such satires reappear throughout the book and leave no disordered practice unscathed. There is the debt collection agency “Calm and Collected, Inc.” that comes after Blake and tries to enroll him in the program cleverly named E Unibus Usurus, “the brainchild of a benevolent senator who billed himself as a ‘compassionate conservative.’” Later, in one of the novel’s funniest scenes, Blake, pressed into service for Calm and Collected, threatens by phone to repossess a indebted woman’s nursing education. Garrett, as a passerby, becomes embroiled in a race riot surrounding a White Lives Matter movement that features Destiny Xanhippe facing off against Kurt Kampf. Hape meets Blake in a bar frequented by white, working-class Catholics that was once called Black Madonna’s Children, though it had recently changed its name to The Deplorables. The various characters in the bars with Hape represent a variety of contemporary views. “You know I love you, Hape, but you’re speaking all out of your ass—out of your privilege, now. Not that, I know I’m biased by my own privilege, too.”

The damaged and reeling Yourrick family slouch toward redemption in part from the help of Father Marto, a pitiable character in his own right as he strives for fidelity while concupiscence punches him from within. Hren describes the complex tensions jousting for dominance within Marto’s conscience in a manner reminiscent of how Graham Greene did the same for the Whiskey Priest in The Power and the Glory.

Marto once had been Catherine’s confessor; now he debates the despairing Garrett about the four last things. Garrett throws down the decisive question: “If there is a God, you must prove him to me in another way. And your Prime Mover does not, absolutely does not stop me from ‘regressing’ back across a terrifying infinity of causes… And so there is no surety that when you get to the end—or the beginning—that God will be waiting there.” Hren is phenomenal in this exchange, as Garrett tears apart the traditional arguments for God using tricks he learned decades ago from Hape. After failing to reason with Garrett, Father Marto eventually leads him to see that love, not argumentation, is what brings a man to God. (Hren tops this scene in his most brilliant creation, Hape’s “The Legend of Lucifer: An Aggiornamento, near the novel’s end. It surpasses C.S. Lewis’s The Screwtape Letters in its originality, cunning, speed, and penetration into the mystery of evil and the tensions within the human soul.)

Father Marto would not have succeeded without the help of Garrett and Catherine’s youngest, Dymphna, their only child that “had really been colonized by their grandma and mama.” The only character in the novel not jaded by sin and society, pious Dymphna, the one shared loved between Garrett and Catherine, kept the alcoholic Garrett from destroying himself. By remaining faithful to God, to both her parents, and to her estranged brothers, the young child concocts a plan for reconciliation just before it becomes too late.

The novel ends where it began—in a graveyard, only this time, Blake is not alone. Thanks to Dymphna, all the novel’s characters are reunited (one implausibly, though for a background appearance). As with the death and resurrection of Christ, death has brought new life to the Yourrick family. In an act of love, Christ died for the forgiveness of sins to reconcile God with man. Our dysfunctional Yourrick family learns that only love can inspire forgiveness, which alone reconciles family members with one another, and with the wider community—on either side of eternity.

David G. Bonagura, Jr. is the author of Steadfast in Faith and Staying with the Catholic Church.

Support the University Bookman

The Bookman is provided free of charge and without ads to all readers. Would you please consider supporting the work of the Bookman with a gift of $5? Contributions of any amount are needed and appreciated!