Introduction and Translation by David G. Bonagura, Jr.

Sophia Institute Press, 2023.

Paperback, 128 pages, $18.95.

Reviewed by David Weinberger.

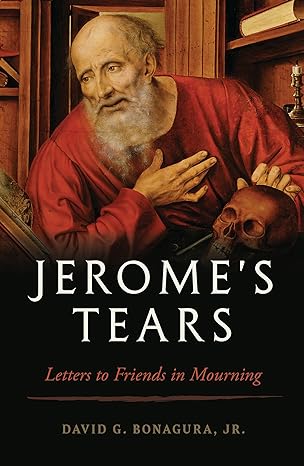

The death of a loved one can be wrenchingly painful. It is during such a time that we fervently yearn for comfort. Where, however, might we find it? There may be no better place to look than the letters of eminent Bible translator and theologian St. Jerome, whose heartfelt prose provides warm words of consolation and confident hope to friends mourning the loss of loved ones. Now, for the first time, in the new book Jerome’s Tears: Letters to Friends in Mourning, seven of these celebrated letters have been translated into English, where we not only see but feel the powerful reassurance they continue to offer us today.

Jerome, who lived in the latter half of the 4th and into the early 5th century, was a priest and scholar of both theology and history. While he is best known for his translation of the Bible from its original languages into Latin, he was a prolific writer on matters of faith and Christian life, including over 120 letters that survive today. His consolation essays, however, are among the most lyrical in antiquity. As translator and editor David G. Bonagura writes, the letters “dedicated to the theme of consolation are the most celebrated genre of all.”

There are, according to Bonagura, three crucial themes that animate these letters. The first is Jerome’s steadfast hope in eternal life following the resurrection of Jesus. Writing to a woman mourning the death of her daughter, Jerome notes that “with Jesus, through whom paradise has been opened, joy follows death. We who have put on Christ and been made a chosen race and royal priesthood, must not be riddled with sorrow over the dead” (emphasis added). The Christian, in other words, while not simply ignoring the pain of earthly loss, is nevertheless encouraged to remember that the current conditions of our existence are ephemeral and that we are in fact made for an infinitely richer and deeper existence—eternity—where mothers and daughters are reunited. He thus exhorts us “not to call [one’s] passing death, but sleep and slumber.”

This is closely related to the second theme of Jerome’s letters, which is not to dwell on the death of a loved one but to celebrate the time, however short, that he or she had here on earth. Writing to Bishop Heliodorus, who grieves the death of his nephew, Jerome encourages him to “not grieve that you lost such a man, but rejoice that you had him.” Likewise, he invites us to recognize that when God calls home those we love, we ought to be grateful for the time we had with them in the first place. For example, after counseling a friend over the loss of his wife and daughters, Jerome urges this prayer: “You [God] have taken my children, whom you yourself had given; you received your maidservant whom you lent to me for my brief consolation. I am not afflicted because you have taken them back, but I give thanks because you have given them.”

This can surely be a difficult attitude to maintain in the face of loss, but it is the third theme that may be the loftiest of all. It is, as Bonagura describes, to strive to overcome our grief and to live a renewed life in Christ. By this, of course, Jerome does not mean that sorrow is wholly inappropriate after losing someone close to us. Rather, he means that after a reasonable period of mourning, we ought to move forward with hope and joy in Christ and his resurrection, for otherwise we demonstrate a lack of hope in the resurrection itself—that is, a lack of belief in the very essence of Christianity. “I condone a mother’s tears, but I ask you to limit your sorrow,” he writes. In other words, while grief is understandable, we must not let it overcome us and blind us to our ultimate hope—eternal life with our loved ones in Christ. “When the passing of a husband is inflicted, I lament his loss,” he sympathizes. “But because it is pleasing to the Lord, I will keep a calm mind.”

Furthermore, Jerome strengthens each of these themes by including numerous scriptural allusions and New Testament teachings, along with a passionate flair that has captured both hearts and minds down the ages. Consider, for example, this passage comparing the philosopher to the Christian on the meaning of death:

This is the opinion of Plato: the entire life of wise men is a meditation on death. The philosophers praise this idea and raise it continually to the sky. But the apostle Paul speaks much more powerfully: ‘By my pride in you which I have in Christ Jesus our Lord, I die every day!’ (1 Cor. 15:31). For it is one thing to try, another to do; it is one thing to live as if one is about to die, another to die as if one is about to live. The former man will die out of glory; the latter always dies into glory.

While passages like this strike us with their beauty, they also challenge us with their defiance of conventional wisdom about death. As Bonagura remarks, however, “the act of consoling, like so many expressions of the human heart, is an art, not a science.” Indeed, it is through this art that Jerome summons us to rise above our mourning and to renew our strength in the Christian hope of eternal life. Easy? No. Consoling? That is for you, of course, to decide.

David Weinberger formerly worked at a public policy institution. He can be found on X (formerly Twitter) @DWeinberger03.

Support the University Bookman

The Bookman is provided free of charge and without ads to all readers. Would you please consider supporting the work of the Bookman with a gift of $5? Contributions of any amount are needed and appreciated!