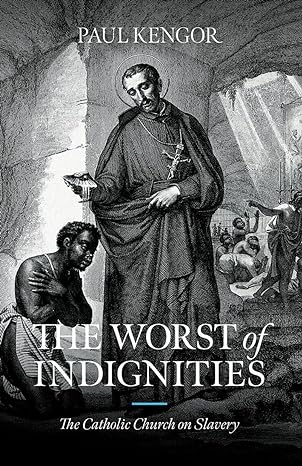

By Paul Kengor.

Emmaus Road Publishing, 2023.

Hardcover, 304 pages, $29.95.

Reviewed by David Weinberger.

When explaining why he was Catholic, G.K. Chesterton observed that there are thousands of reasons all amounting to one reason: that Catholicism is true. Of course, assessing the truth of Catholicism is no small undertaking, but a new book reveals that at least on one very important issue the Church has been right since the beginning: its opposition to slavery. In The Worst of Indignities: The Catholic Church on Slavery, historian Paul Kengor not only chronicles this history and many of the heroic Catholics who opposed human bondage along the way, but also the prevalence of slavery throughout the ages, including its persistence in parts of the world today. At every step, Kengor shows that the Catholic Church has led the fight against it—and that it continues to do so in our time.

Although many modern Americans believe that slavery was primarily a matter of whites enslaving blacks—due, of course, to America’s shameful involvement in the Atlantic slave trade, where enslaved Africans were shipped to the Americas—history reveals that for thousands of years slavery was practiced by virtually every culture and every race of people. For example, long before the Atlantic slave trade began in the late fifteenth century, slavery was prevalent in Africa itself, where blacks and Muslims had been enslaving other blacks for centuries. Moreover, while the European enslavement of Africans is well known today, lesser known is the African enslavement of Europeans, including the English. As Kengor notes,

According to one source, at one point there were more English men and women held as slaves in Africa than Africans kept as slaves in English colonies. Professor Alan Gallay writes, ‘From the 1530s through the 1780s, over one million Europeans were held as slaves in North Africa, and hundreds of thousands more were kept in bondage under the Ottomans in Eastern Europe and Asia. In the mid-seventeenth century, more English were held as slaves in Africa than Africans were kept as slaves in English colonies.’”

Moreover, slavery was also ubiquitous among natives in the “Americas” prior to the arrival of Christopher Columbus and the Europeans. For instance, the Mayans and the Aztecs were known for their particularly brutal forms of human bondage and even human sacrifice. Furthermore, slavery among Indian nations persisted long after the United States was founded in the late eighteenth century. Indeed, tribes such as the Choctow and Chickasaw continued to hold black slaves after the emancipation proclamation of 1863, since the U.S. government treated them as separate political entities.

Likewise, Eastern nations such as China and India, and various Muslim civilizations throughout the Middle East also trafficked in human slavery for hundreds or even thousands of years before the Atlantic slave trade began. Simply put, until the West began abolishing it in the nineteenth century, slavery was universally accepted around the globe for millennia.

It was Jesus and the Catholic Church that catalyzed a change in the world’s approach to slavery. As Kengor notes, “Jesus not only became a slave himself but healed slaves.” For example, when Jesus heals the slave of a Roman centurion in Luke 7, he “treats the slave not as a slave but as a person. The slave is spared by Jesus with no hesitation, no questions, no objections, no distinction, and certainly no discrimination because he is a slave.” Moreover, Jesus’ attitude of love redounded to the Christian community over the centuries and ultimately provided the pretext for its opposition to slavery in years to come. For example, at the Council of Agde in 506 AD, the Church vowed that, “Concerning slaves of the Church, if any bishop shall reasonably have bestowed liberty freely upon well-deserving cases, it is pleasing that the liberty conferred should be cared for by his successors, with whatever the manumitter conferred on them in granting liberty… The Church shall take care of freedmen legitimately freed by their masters if necessity demands it.”

Note the Church’s vow to take care of freed slaves. Of course, modern critics may complain that such a pronouncement can hardly be regarded as enlightened since it speaks of “slaves of the Church.” Why, after all, should we be impressed by a church that admits to holding slaves? Such criticism, however, betrays a poor understanding of both history and moral progress. Moral advancement is seldom clear cut. It instead occurs incrementally and within the context of wider society. Historical actions and statements must therefore be judged relative to their time period—not by our twenty-first-century standards. Relative to the sixth century, where (as we saw above) slavery was common practice around the world, an official statement like this by a major institution was unique for recognizing that there are any moral obligations to slaves at all. As Kengor puts it, “At this time in human history—namely, more than fifteen hundred years ago—this action at Agde was very forward-looking and merits praise rather than condemnation. This was not the twenty-first century; it was the start of the sixth century. Societal standards were completely different.”

Furthermore, this was no isolated pronouncement by the Church. In fact, Kengor highlights dozens of major church councils and papal statements on slavery throughout the early and later Middle Ages, long before other major governing bodies, whether secular or religious, showed a similar recognition of the evil of human bondage. Consider, for example, the papal proclamation of Pope Eugene IV in 1435, which was at least several decades before the start of the Atlantic slave trade, titled “Against the Enslaving of Black Natives from the Canary Islands.” In it, the pope commanded that “[t]hese people are to be totally and perpetually free, and are to be let go without exaction or reception of money. If this is not done when the fifteen days have passed, they incur the sentence of excommunication by the act itself.” In other words, Christians risked excommunication from the Church if they enslaved local natives. Explicit condemnations like this, as Kengor documents, are made repeatedly by both popes and councils down the ages and even into today.

Before looking at modern slavery, however, it is worth mentioning a point Kengor stresses. Although the Church itself has an impressive anti-slavery record, this does not mean that individual Catholics, whether laypeople or even members of ecclesial bodies, always followed suit. On the contrary, there are plenty of examples of Catholics, including priests and even bishops, who acted contrary to Church teachings and who committed horrendous acts of evil. Thus, one must be careful not to confuse the failure of individuals—even individuals of high authority—with the clear and consistent record of official Church statements and councils going back to the earliest centuries of Christianity.

After exposing the reader to this record, Kengor gives fascinating biographical accounts of early Catholics who led the fight against slavery, including many who were former slaves themselves. One notable example is Saint Patrick. In the early 400s, Irish pirates raided Britain, where the young Patrick was captured and brought to Ireland and enslaved for six years. Rather than growing angry and embittered, however, “Patrick saw this as a divinely ordained punishment and ultimate call from God,” observes Kengor. Patrick, in fact, stated that during his captivity he had an experience of God which led to his escape to Britain and ultimately to his conversion to the faith. Later, however, he returned to Ireland and not only converted the people to Christianity but also became an outspoken critic of slavery. As one scholar cited in the book writes, “Patrick, the former slave, gave nascent voice to the ideals of human rights and anti-slavery in Western Europe.” Because of his heroic efforts, we continue to recognize the feast of St. Patrick each March to this day.

Kengor then turns his attention to the Church on modern slavery. Although little known today, chattel slavery still exists in pockets of the world. For example, in modern Sudan, Kengor explains, “slaves are predominantly black Christian slaves seized by and taken into possession by black African Muslims, in the form of abduction and forced servitude.” Nor is this human bondage confined to Sudan. Chad, Saudi Arabia, Libya, Mauritania and other places in the Middle East also practice chattel slavery that includes beatings, genital mutilation, and other forms of torture up to and including death. While these facts are seldom reported today, the Catholic Church has refused to remain silent, issuing letters condemning these atrocities and even founding organizations to help end them. As one example, Kengor describes how “[t]he Holy See to the United Nations co-sponsored a ‘landmark summit’ on the issue of ending human slavery in our day. Co-sponsoring the event was the ‘Santa Marta Group,’ an organization of Church leaders that Pope Francis founded to abolish human trafficking.” The pope, moreover, has also published letters and documents, including one as recently as 2020, calling attention to and condemning the remaining practitioners of slavery in our time.

It is a shame, however, that these facts have generated so little attention, especially from the same outrage industry whose mission is to foster endless guilt for America’s sins. But, as black scholar Thomas Sowell explains, the lack of coverage by this industry is really due to politics and ideology: “Why so much more concern for dead people who are now beyond our help than for living human beings suffering the burdens and humiliations of slavery today? Why does a verbal picture of the abuses of slaves in centuries past arouse far more response than contemporary photographs of present-day slaves in Time Magazine, the New York Times or the National Geographic?” “Clearly, the ability to score ideological points against American society or Western civilization, or to induce guilt and thereby extract benefits from the white population today, are greatly enhanced by making enslavement appear to be a peculiarly American, or a peculiarly white, crime.”

But as Kengor makes clear, it is not. Slavery, in fact, was everywhere for the vast majority of human history, and it still survives in places today. While Western civilization deserves credit for helping end it, the Catholic Church stands alone in both its early recognition and its consistent conviction that slavery is evil. And that history deserves to be better known.

David Weinberger formerly worked at a public policy institution. He can be found on X @DWeinberger03.

Support the University Bookman

The Bookman is provided free of charge and without ads to all readers. Would you please consider supporting the work of the Bookman with a gift of $5? Contributions of any amount are needed and appreciated!