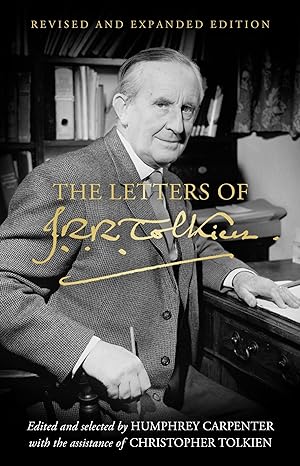

Edited by Humphrey Carpenter and Christopher Tolkien.

William Morrow, 2023.

Hardcover, 432 pages, $40.

Reviewed by Isaiah Flair.

It is always a privilege to travel through the articulate mind of the man who crafted the mythology of Middle-Earth. In his lifetime, that man wrote a prodigious proliferation of letters, many of which are included in the book aptly called The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien. Some of the letters address the topic that Tolkien fans care about most: his fantasy fiction books, particularly The Lord of the Rings and The Silmarillion.

In a letter to publisher Milton Waldman in 1951, Tolkien provided a look behind the scenes of his writing processes: “Many children make up imaginary languages. I have been at it since I could write.” Tolkien’s passion for languages, including those that he created for his books, is well-known. Yet, in this letter, he focused on a different passion, one that was based on a love for myth and fairy story, and “above all for heroic legend on the brink of fairytale and history, of which there is far too little in the world.”

Tolkien was describing the kinds of books that he wanted to read, but couldn’t find enough to suit him. He lamented the lack of English books, in particular, that combined myth and fairytale in the way that he wanted. So, he decided to write the books that he wanted to read, which is what many of the best authors do.

In the part of the letter that sounds a lot like his blueprint for The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien writes, “I had a mind to make a body of more or less connected legend, ranging from the large and cosmogonic, to the level of romantic fairy story—the larger founded on the lesser in contact with the earth, and the lesser drawing splendor from the vast backcloths.” He wanted his story to “possess the tone and quality that [he] desired” (represented by the rustic ways of the hobbits), while having “the fair elusive beauty that some call Celtic” (represented by the mystical magic of the elves). That plan came to glorious fruition, and was even made into a movie trilogy by Peter Jackson.

Intriguingly, Tolkien also delved into a storytelling mechanism that he referred to as the Machine. Essentially, the Machine is the way that power is wielded in a story to get what is wanted. In many books and movies, the Machine is some sort of personal power. For example, in superhero movies, supervillains usually find some way to give themselves superpowers, which they then use to get what they want. However, Tolkien wanted a substantial focus on using external devices “instead of development of inner powers or talents.” The external devices that he chose included magic rings.

LOTR fans know that Tolkien had the pen of a poet, and his letters establish that he had the soul of a poet as well, often describing the people and places he knew in real life with a lyricism fit for the best of novels.

In a letter written to his son Christopher in July 1972, Tolkien spoke of his wife, Edith, who inspired the character of Lúthien Tinúviel in the Silmarillion. “I never called Edith Lúthien, yet she was the source of the story that became the chief part of the Silmarillion.”

“[The story] was first conceived in a small woodland glade filled with hemlocks…”

“In those days, her hair was raven, her skin clear, her eyes brighter than you have seen them, and she could sing, and dance.”

The character of Lúthien, inspired by Tolkien’s wife, was said to have been the fairest maiden who ever lived in the fictional world that Tolkien created. Tolkien described Lúthien in terms that quite precisely matched how he described his wife, including beautiful dark hair, bright eyes, glowing skin, and enchanting singing.

With Lúthien, Tolkien took the emotional effect of singing one step further by giving it the power to affect the physical world. “And the song of Lúthien released the bonds of winter, and the frozen waters spoke, and flowers sprang from the cold earth where her feet had passed.” Interestingly, the fairy-like character of Lúthien wed a mortal man, Beren, which suggests how Tolkien viewed his place in the real-life romance that he lived with his beloved wife. For Tolkien, his affection for his wife continued even after she passed away in November 1971, the year before he wrote the July 1972 letter to his son. Of their lives together, he poignantly wrote:

Someone close in heart to me should know of the things that records do not record: the dreadful sufferings of our childhoods, from which we rescued one another… For ever, especially when alone, we still met in the woodland glade, and went forth many times, hand in hand, to escape the shadow of imminent death before our last parting.”

Great writing is a chronicle of people and their relationships. In the modern era, relationships are looked at very differently than they were in previous centuries that Tolkien immersed himself in through reading. We see this in his letters, where Tolkien’s description of his relationship to his wife betrays a mythological character. It is not the goal of modern individual autonomy that Tolkien sought, but that of mystical union.

The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien is a treasure trove of insights from the mind of Tolkien that we can read and then revisit from time to time, with each visit including another set of Tolkien’s letters for joy and reflection. There is much in the letters to consider, much to learn, and much to apply to life as it could be in a future yet to be written.

Isaiah Flair is a content creator and marketing strategist who lives in the Pacific Northwest, between the evergreen forests and the sea.

Support the University Bookman

The Bookman is provided free of charge and without ads to all readers. Would you please consider supporting the work of the Bookman with a gift of $5? Contributions of any amount are needed and appreciated!