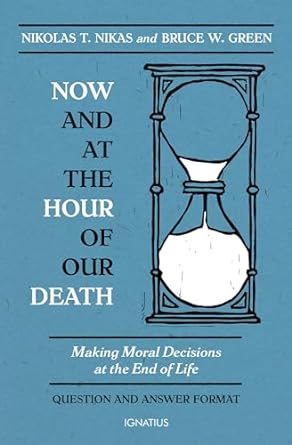

By Nikolas T. Nikas and Bruce W. Green.

Ignatius, 2024.

Paperback, 213 pages, $18.95.

Reviewed by Robert Grant Price.

While washing the dishes, I listened to a shock jock philosophize about doctor-assisted suicide. (He arrived at this philosophical tangent after first mocking people who believed in the “old man in the clouds.”) If a person is suffering and there is technology to help them achieve peace, why not help them to a compassionate death?

“You wouldn’t do that to a dog,” the shock jock said. Meaning you wouldn’t let a human suffer like we let dogs suffer. You’d put the human down.

He has it backwards, of course. You wouldn’t do that to a human. You put down a dog because it is a dog. You wouldn’t put down a human like you would a dog because a human’s life is worth more than a dog’s.

At least, that’s what most people used to think. Now dogs and humans occupy the same moral category. The generosity extended to the dog is now extended to the man.

This is, of course, moral philosophy as espoused by a provocateur and sensationalist that’s meant to be provocative and sensational. Those who want something more thought through (i.e., talk about death and dying that hasn’t been infused with confusion and relativism) might want to reach for Now and at the Hour of Our Death.

The book is a handbook for a Catholic death written by Nikolas T. Nikas, co-founder and president of the Bioethics Defense Fund, and Bruce W. Green, a former dean and law professor who serves as special counsel to the Bioethics Defense Fund. Presented in a Question and Answer format and split over eight parts, Now and at the Hour of Our Death offers answers to 123 questions a curious person might have about their death. The appendices include, among other things, an essay on how to form a working conscience, a glossary, and an example of what a Catholic medical power of attorney might look like—useful for those who might not be able to afford to pay a lawyer to devise one for them. Reading the book is, quite literally, like having two lawyers explain the legal and moral ins and outs of end-of-life care.

This book shines in balancing the many personas of the book. It is a legal textbook in one way and a self-help book in another. It examines philosophy and theology in one section and in the next digs into cultural criticism. It’s a Q&A that wants to be nibbled at, left alone, and picked up again, and a serious book that needs to be read from front to back. It talks in cold legalese here, jovial church-ese there. It talks about death, but it also talks about life. It’s a sad book that the authors insist is about “happiness—happiness not only at the hour of our death but happiness now.” By happiness, they mean the happiness “found in the good of a person’s soul,” which means union with God. Achieving a happy death “will be the result of our pursuit and enjoyment of happiness on earth right now.” And so the authors speak at length about the need to live a God-focused life that can prepare the reader for the pain and suffering that await them.

There was a time when a book like At the Hour of Our Death might have drawn a wide readership. Vast swathes of people held to the same basic precepts about how to live, and they would have turned to it for answers about how to die. But ever since Christianity was evacuated from Western public institutions and the broader culture, morality has been treated as a private concern, something we invent for ourselves because there are few universals to which we can turn.

To assert as a moral precept that doctors should not kill their patients, as Nikas and Green do, triggers a reaction among those, like the loudmouths on the radio, who have elevated autonomy above all other virtues. For these people, morals are personal property. To show that public morals are not a private concern brings an extremist reaction: “Get off my lawn!”

Nikas and Green detail how the elevation of personal autonomy over other virtues, the medicalization of dying, and other changes to the culture have undermined end-of-life decision-making. They walk the reader through the corruption in a plain, orderly style. For example, about the abuse of the word, by which so much public opinion has been reframed and clear thinking obfuscated, they show how degraded language leads to degraded action. The phrase “death with dignity,” to take one example, “is often used as a euphemism for premature death, sometimes with the assistance of another person, and usually because the dying person is presumed to have a life that is not worth living or because society has declared that the life of the dying is a ‘burden.’ Thus, ironically, the phrase ‘death with dignity’ is used precisely to deny the true dignity of the dying person.” Language of this sort means well, but as Nikas and Green demonstrate, it can lead a person to accept views about death and murder that they wouldn’t otherwise accept.

Many of the more obnoxious pro-death advocates will find this book to be deeply unfashionable and unlikeable. They will not like the cool undressing of their ill-thought positions on dying, nor will they likely care much for orthodox Catholic doctrine that runs through the book. But they won’t read this book, and Nikas and Green aren’t writing to them, anyway. They are, instead, writing to Catholics who still want a Catholic view on death and to anybody else who still thinks that “The soul always takes priority over the body.”

Nikas and Green implore readers to read the book while they are still mentally and physically sound. When loneliness, pain, and suffering come, the lethal temptations offered by budget-conscious hospital bureaucrats and death-dealing doctors might be hard to deny. The direct, honest speech of Nikas and Green, beautified by Ignatius Press’s always stunning book design, can help a person think through the problems of dying before they’re too weak to think.

As for whether humans deserve the same sort of mercy offered to dogs, readers can consult Question 48, “I want to help my loved one die to stop his suffering. How can that be wrong?” Here readers will find that, contra the shock jock, putting down a loved one like you put down Old Yeller is “false mercy” and a “perversion of mercy” and not merciful at all. “The error of judgment into which one can fall in good faith does not change the nature of this murderous act, which must always be forbidden and excluded.”

Robert Grant Price is a university teacher and communications consultant.

Support the University Bookman

The Bookman is provided free of charge and without ads to all readers. Would you please consider supporting the work of the Bookman with a gift of $5? Contributions of any amount are needed and appreciated!