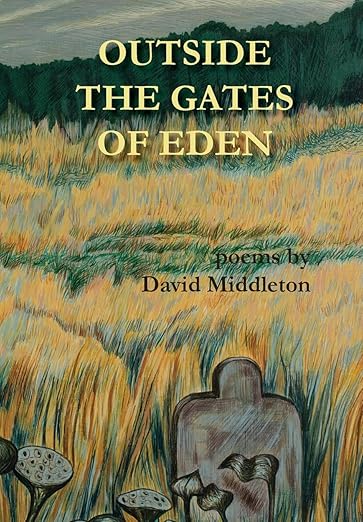

By David Middleton.

Measure Press, 2023.

Hardcover, 114 pages, $25.

Reviewed by Madeleine Austin.

David Middleton’s Outside the Gates of Eden is a collection of formal poems rooted in contemplation of the Book of Genesis. What does it mean to stand outside the gates of Eden, considering the fall and humanity’s eternal desire to return from our banishment? Poetry, Middleton contends, is the way “by which humankind can most fully celebrate, here and now, even in a post-Edenic world, the mystery of creation, its orderliness and beauty, its origin and end, its purposefulness, and, above all, the wonder of its merely being.” The poet, then, as Middleton put it in his 2013 Hillsdale College lecture, is tasked with “singing us back to Eden,” remembering and transmuting our collective understanding of the mysteries of being to the successive generation through verse. Middleton captures this role through Demodokos—the bard who moves Odysseus to tears at Alcinous’ palace feast in Scheria. The prose of the collection’s closing essay, “The Striking of the Lyre: Demodokos in Modernity,” gives the reader the clearest insight into Middleton’s vision—but only at the close of the bard’s song.

Outside the Gates of Eden holds an assortment of poetic forms, deepening and refining themes Middleton has engaged with in other collections. A shared narrative voice unifies the distinct characters who populate the collection. Mature, contemplative, sometimes nostalgic, his voice is that of a bard looking back on the fruits of his labor and the labor itself. The story has been written, etched into history rather than open in its future possibility—a state that seems sometimes to please and sometimes to challenge the speakers of the poems. Some are odes or memorials, such as “The Voyage of Pytheas” and “Calling Down the Birds.” Many marry themselves to paintings—most frequently those of Millet—as well as other poems, verses, or books. Some tiptoe into more explicit social commentary, such as “Lee in Darkness,” “Modern Times,” “Infinitives,” and “Headmaster, Mother, Son.” The unifying characteristic of the poetic array is its formal meter. In “Infinitives,” the narrator proclaims:

No one rose to go as I stressed again

That rules of verse can set a poet free –

Caesura, line break, meter, rhyme, and stave—

Significance bound up in space and time

Like particles infinitives unsplit

In atom, grammar, host, the maker’s art.

The collection’s initial pages and description belies its sometimes comic, irreverent tone. In a few instances, vivid, cheeky, sensual (see “To Her Who Bears These Verses”) voices change the expected tone of the collection. Such surprises can be found in poems like “4:00 AM” and “Cholesterol.” Many of the poems are visceral, descriptive, and sometimes discomforting as they grapple with our common human condition, especially aging, sickness, and death. This is no mere collection of idyllic pastoral poems, as one might assume at first glance. Rather, true to its theme, the collection contends with the realities and mysteries of life post-Eden alongside more descriptive, pastoral poems of creation.

Outside the Gates of Eden is in direct, varied conversation with the Western canon through the fine arts, history, theology, and more. Usually, these are not passing references. Middleton’s poems are an inheritance deeply embedded in the tradition, and a mere casual familiarity does not suffice for appreciating most of the works. Some poems have introductions, others epitaphs, some have notes, but many stand alone. The mature, educated reader with an established appreciation for the “permanent things” will revel in Middleton’s deep engagement with the tradition.

Middleton shines brightest in his rooted, placed poems—the more particular, the better. These poems represent Middelton in his truest form, as the Shreveport Poet. The concrete, heightened verse of poems like “Town and Country,” “Porches,” “Bringing Home the Cows After Eden,” and “Fairgrounds” flash the brightest glimpses of Eden. “Porches” begins:

The sand and gravel road, smooth asphalt now,

Passes beside the churches and sunken stones

Of kin both dead and living yet awhile

In memories of one who left and stayed.

This is but one sample from a dozen rich poems of place and memory. “Fairgrounds,” for example, captures the 1961 Louisiana State Fair in Middleton’s home of Shreveport:

And now they’re ready for the carousel,

Holding tight to the ponies on their posts

Going up and down round and round

And that’s enough: it’s time to go back home.

The poem’s detailed experience could have been experienced yesterday as easily as sixty-four years ago, but it evokes such a sense of place and particularity. Affection is the thread running through these poems of place and people. This affection is multifaceted; it is the affection of storge rather than mere romantic nostalgia. This affection is not necessarily always positive, romantic, or easy. While the speaker of “Fairgrounds” prays, “Let this be forever as it is,” the collection teems with unabashed certainty that “as it is” is more than just romantic sentiment; these affectionate poems of friendship and place resonate the full truth in their song of what it is to be human.

Ekphrastic poems make up a large share of the collection, usually after Millet but sometimes Constable or Poussin. Some of these poems are more descriptive, others more meta-reflective; the former gives insight into the painting, like a book can capture the internal processes of a story in ways a film cannot. The latter more often relies on seeing or knowing the original artwork. I first ventured to read the poems without their painting references, which are not printed in the book, which suited the descriptive poems like “Shepherdess and Flock at Sunset” and “Peasant Woman Watering Her Cow.” These poems operated within the bounds of the moment captured by the painting, delighting the listener with stanzas like:

But here, for once, a blinding sunset bursts

So bright the sun itself is lost in light

Whose white core sets the lower air aflame

And spreads along a thread of plain and sky.

These poems are so vivid and bursting with descriptive imagination that without the dedication, one might not know that they exist within paintings. However, the vast majority of these poems, like “Peasant Girl Day-Dreaming,” “Reading Lesson,” and “First Steps,” “Noonday Rest,” and “The Hay Wain,” break the third wall, interjecting the commentary of the speaker and taking the listener out of the moment to highlight some broader, but only suggestive, context:

Millet, too, learned in 1839,

His first submission—turned down by the Salon,

A painting in a drawing lost and found,

Bound pages in an artist’s Book of Hours,

Referencing the artwork, as well as reading the frequent quotations and information about the paintings, ended up essential to a full appreciation of most of the ekphrastic works, despite my attempts to the contrary. This disappointed me, as it meant time spent looking at a screen as opposed to the ideal method of rocking on the porch, reading aloud with a drink in hand.

Outside the Gates of Eden posits that while we can never get back to Eden, or reach Acadia, we can reconcile ourselves to this past and enrich our being in the present. Poetry—specifically the music of measured verse—serves as the greatest way of looking into the human condition and our vestiges to an irretrievable Eden. Poetry “remains the one power by which man might still return to his long sojourn through history to a realm where Edenic innocence and consciousness existence, both in time and beyond time, are reconciled at last.” It is the Demodokos who is ordained to receive and transmute this knowledge and serves as a vessel of reconciliation:

For I was also called, ordained, my gift

Not given by a bishop but a voice

That left me with the silence of the page

And language from a common lexicon

The Holy Spirit blessing grape and grain.

In the last entry, Middleton posits that “our greatest verse and the mystery of human existence are one,” evidenced by its inimitable resonance with our souls. Experiencing the collection, I’m inclined to agree. Outside the Gates of Eden is the bountiful fruit of a distinguished career, worthy of the task Middleton sets for himself. As Middleton writes of the quotidian array in “Two Poems on Quietude”:

Driving cool analytic mind away

From reminisces the heart knows best,Those images so luminous, discrete,

Connected till a life is made complete.

Madeleine Austin lives in Pittsboro, North Carolina with her husband, Joshua. She is a graduate of the Virginia Military Institute and the University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill. When Madeleine is not playing her banjo, she works as an intelligence officer in the U.S. Army Reserves.

Support the University Bookman

The Bookman is provided free of charge and without ads to all readers. Would you please consider supporting the work of the Bookman with a gift of $5? Contributions of any amount are needed and appreciated!