By Christopher J. Scalia.

Regnery, 2025.

Hardcover, 352 pages, $32.99.

Reviewed by Nadya Williams.

Earlier this summer, The New York Times published yet another jeremiad on fiction-reading men going the way of the dinosaurs. “Why Did the Novel-Reading Man Disappear?” queried journalist Joseph Bernstein. Coincidentally, that same week The Atlantic ran a piece on this same phenomenon by the novelist and editor Jeremy Gordon, “The Real Reason Men Should Read Fiction.”

I read somewhere in the vicinity of one-hundred books per year, give or take. Also, I’m not a man—and therefore I’m part of the half of the human race that is purported to read more novels. But in some recent years, the nonfiction on my reading list has well outstripped the fiction. The reasons are complicated. Partly, the explanation is that I am picky about novels and have a high bar for quality. Life is short, and in this mortal coil, we can only fit in a limited number of books during a lifetime. If you want to get really verklempt about it, you should think alongside author and prolific book reviewer Joel J. Miller about “All the Books You’ll Never Read.” Then weep.

But there is another reason for my pickiness, specifically as a conservative Christian reader. The books we read form our minds, spirits, souls. What would you like to be formed by? A little over a century ago, educator Charlotte Mason argued against giving children twaddle—books that were perhaps entertaining but not edifying or inspiring the reader towards anything higher and better. The problem is, there is an overabundance of twaddle for adults too. Contemporary twaddle is a category all unto itself. Perhaps it is too many encounters with such low-quality fare that turn off some readers from fiction altogether.

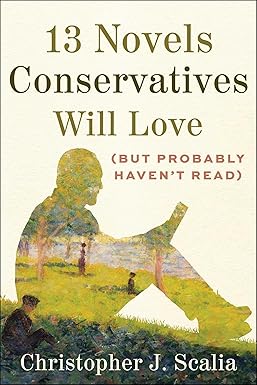

Still, there is plenty of excellent fiction out there that is worthy of forming the conservative imagination today. It’s just that sometimes even people who love to read novels find themselves in a bit of a rut and need new suggestions. It is with this conviction in mind that literary critic (and avid novel-reading man) Christopher J. Scalia wrote his new book, 13 Novels Conservatives Will Love (But Probably Haven’t Read). The conservative bookshelf has its regular canon, of course—Scalia notes a brief list of such perennial favorites as the novels of J.R.R. Tolkien, George Orwell’s 1984, and Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged. This list is good, but it would be even better if it were broader than the usual suspects:

The problem is that our reliance on them obscures the significance and abundance of conservative ideals and principles in literature more broadly. The result is a sort of self-inflicted myopia to many cultural contributions of our ideological predecessors, and even of the exemplary literary expressions of our shared beliefs from writers who probably would not call themselves conservative. We stand on the shoulders of giants—but there are more giants than we realize.

It is an exciting vision, built on several foundational assumptions about our literacy habits and how they shape human flourishing. First, we need more beauty in our lives, which is something good novels offer. Also, novels shape our affections to love others better—good fiction teaches us compassion and empathy. Last, but not least, “conservatives should embrace the novel because it is one of the great achievements of Western culture. It is the form through which many of the most talented creative minds of the past three centuries have expressed their ideas, explored their times and places, and both reflected and formed the minds and characters of their audiences.” As a classicist, I’m obligated to add that this function of the novel already began to some extent in the ancient world. The last three centuries should not get all the credit for inventing this genre, although modernity’s credit for bringing the novel to greater prominence is well earned.

These arguments for the value of reading novels for conservatives readily echo historian John D. Wilsey’s exhortations in his recent book Religious Freedom: A Conservative Primer. Like Scalia, Wilsey sees the need for enhancing the conservative imagination. He argues for aspirational conservatism—meaning, a conservatism that delights in the good, the true, and the beautiful in the American past and present. The quest for such beauty, goodness, and truth must include the arts, music, film, and especially great literature. You, a single individual, might not save the world, but you could become a better thinker, citizen, neighbor, and friend through reading good novels. In other words, while reading novels is good for individuals, a society filled with thoughtful novel-reading citizens is likely to be a better society, one more conducive to human flourishing.

So how did Scalia select the thirteen novels for this book? He readily admits that the process was not exactly scientific. Someone else might have selected a different batch, as a key condition was Scalia’s own enjoyment of these thirteen novels. Furthermore, while conservatives have enjoyed the novels of, say, the Russian or French masters in translation, Scalia decided to stick to English-language novels from the mid-eighteenth century to the present. The earliest novel in the book is Samuel Johnson’s Rasselas, published in 1759. The most recent is Christopher Beha’s The Index of Self-Destructive Acts, published in 2020. Noteworthy is the criterion reflected in the second part of the book’s title—Scalia sought out classic novels that are less well known among conservatives. Part of the intended delight of this book, as a result, is this scavenger hunt vibe—the possibility of introducing readers to great novels they have not read. Scalia has succeeded in this goal. Out of the thirteen novels discussed in this book, I’ve only read one—Leif Enger’s Peace Like a River. That said, to prove that I am not a total heathen, I should note that I have read other novels by four other authors Scalia selected. In other words, his gamble at finding less familiar gems of better-known authors paid off.

So why would conservatives love these novels—and why would they benefit from reading them? Several themes come through repeatedly. First, the pursuit of virtue matters; great novels repeatedly show the beauty of virtue and the ugly tragedy of vice. Happy outcomes are never guaranteed for the virtuous, but the consequences for those who reject them are dire. The eponymous protagonist of Frances Burney’s Evelina grows in her awareness of manners and virtues over the course of the novel. After a dangerous and nearly fatal detour into treason, Edward Waverley, the protagonist of Sir Walter Scott’s Waverley likewise discovers wisdom and corrects the course of his life. But some of the characters of George Eliot’s Daniel Deronda experience what happens if wisdom never arrives—or comes too late. Likewise, the protagonists of Christopher Beha’s The Index of Self-Destructive Acts are living lives that are spiraling into all the canonical vices, with harrowing results. These are cautionary tales presented in the form of beautiful fiction, Scalia shows; these novels are never simplistically moralistic.

Second and related, several of the selected novels show the weighing of eternal priorities over the ephemeral. This applies both in the spiritual sense and in terms of practical living. The protagonists of Samuel Johnson’s Rasselas seek to find their calling and a greater meaning in life. On the other hand, the dystopian vision of P. D. James’s The Children of Men shows the nightmare of a society without children—a world where no child had been born for a quarter-century. Leif Enger’s Peace Like a River weaves miracles seamlessly into what appears to be, otherwise, an exploration of an ordinary family’s misfortunes. Muriel Spark’s The Girls of Slender Means is “a particular kind of murder mystery; it’s a martyr mystery.”

And third, many of the novels proceed from a conservative Christian view of human nature—that our nature is fallen, and sin is a tragic yet unavoidable part of life in this world. Such is the case in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Blithedale Romance, which condemns utopian impulses and the desire to make a better world entirely through man-made reform. V. S. Naipaul’s A Bend in the River shows “civilization without victimhood”—but sin, alas, is ever present.

A distinct thread connecting these novels is the conscious reflection within them on the importance of reading in forming a healthy and virtuous imagination. Authors over the past three centuries have included this message in their fiction. Particularly dangerous, time and again, is overly romantic and unrealistic reading that causes the reader to lose grasp on the responsibilities to which reality summons him. Edward Waverley’s irresponsible reading habits directly lead him on the path to treason. Evelyn Waugh’s Scoop is a satirical yet frighteningly familiar tale of bad journalism and the corruptive power of its writing and its reading. Presented more as oral tales written down, Willa Cather’s My Ántonia and Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God both show the power of redeeming narrative. The stories we tell ourselves—and others—matter a great deal. Their significance is civilizational in scope.

“It’s a common and accurate intra-conservative complaint that we’re not good at telling stories,” Scalia muses in his conclusion. In the age of AI, excessive doom-scrolling habits, and universal distractions, the problem is only getting worse. But this problem is fixable, so long as we keep reading widely and reading well.

Nadya Williams is interim director of the MFA in Creative Writing at Ashland University. She is books editor at Mere Orthodoxy and the author of Cultural Christians in the Early Church (Zondervan Academic, 2023), Mothers, Children, and the Body Politic (IVP Academic, 2024), and the forthcoming Christians Reading Classics (Zondervan Academic, November 2025).

Support the University Bookman

The Bookman is provided free of charge and without ads to all readers. Would you please consider supporting the work of the Bookman with a gift of $5? Contributions of any amount are needed and appreciated!