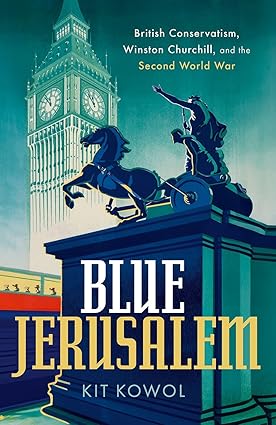

By Kit Kowol.

Oxford University Press, 2024.

Hardcover, 352 pages, $38.99.

Reviewed by Daniel Pitt.

In Benjamin Disraeli’s great novel, Lothair, Mr. Phoebus remarks, “Books are fatal; they are the curse of the human race.” Mr. Phoebus adds that “Nine-tenths of existing books are nonsense, and the clever books are the refutation of that nonsense.” Dr. Kit Kowol’s book Blue Jerusalem: British Conservatism, Winston Churchill and the Second World War is, in Mr. Phoebus’s dichotomy of books, one of those clever books. More significantly, it certainly refutes a lot of the nonsense written about the Second World War (WWII), and especially the narratives around conservative thought and thinking during the period covered in his book. This aspect of Blue Jerusalem is most pleasing. The book has something for everyone who takes an interest in this bit of history as it covers war strategy; the different narratives and concepts of the war, such as “The People’s War,” “Churchill’s War,” and “Chamberlain’s War;” great figures of the era such as Sir Winston Churchill and the Canadian Lord Beaverbrook; the general election of 1945, and even post-war conservatism. Many of these subject matters break new ground in our understanding of WWII, especially within the British context.

Despite Churchill being namechecked in the subtitle of the book, Churchill is not the protagonist in the book. Please do not misunderstand me here; Churchill is mentioned or cited hundreds of times. Notwithstanding that I am a paid-up Churchillian, this is a major strength of the book, as the unstoppable force or the juggernaut-esque stature of Churchill can and does overshadow other events and happenings during this period. Kowol has not allowed this to materialize in his book. Besides, there are numerous and splendid books on Churchill, such as the highly acclaimed Lord (Andrew) Roberts’s Churchill: Walking with Destiny, Dr. Larry P. Arnn’s Churchill’s Trial, and Sir Martin Gilbert’s Churchill, A Life. I suggest that Blue Jerusalem ought to be read alongside these great works. There are, however, some great Churchillian remarks by the great man in the book, so there is no need for concern on that level.

As someone with an interest in ideas, particularly intellectual conservatism, the most fascinating aspect of Blue Jerusalem is Kowol’s engagement with conservative thought. There is a narrative that claims that during the war and the post-war period conservatives did not do any thinking in Britain, and there was a lack of engagement with conservative ideas. Moreover, it is argued that Churchill himself was only really interested in foreign policy, and his domestic policies revolved around meat and housing, that is, removing food rations (the last of the food rations were lifted in 1954) and building houses. Kowol’s book challenges this narrative, especially the one about the lack of thinking about a conservative future for Britain and her empire after the war had been won. Kowol thus writes: “While the leadership of the Conservative Party did undergo a profound shift under Churchill, it remained intellectually active, and actively engaged on the home front.”

George H. Nash, in his seminal work The Conservative Intellectual Movement in America Since 1945, writes:

Conservatism in America after World War II was no closet philosophy or esoteric sect, at least not for long. It was a decidedly activist force whose thrust was outward toward the often uncongenial America of the mid-twentieth century. An intellectual movement in a narrow sense it certainly was, yet one whose objective was not simply to understand the world but to change it, restore it, preserve it.

I think Kowol’s book shows that this was also the case for conservatism in Britain. Indeed, in Britain, attempts to trace and describe a body of principles or thinkers that compose conservatism in the United Kingdom, in the way that Dr. Russell Kirk did for the Anglo-American conservative tradition in The Conservative Mind, have been relatively few. Nevertheless, I have argued before that events, such as wars, do initiate reflection by conservatives. I have written for Conservative Home in the UK that “I think that the dates of when seminal conservative texts were published are illuminating.” To provide just two examples, Edmund Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France, published in 1790, and Quintin Hogg’s The Case for Conservatism, published in 1947. I also note that there were other works published during the 1940s and 1950s, The Conservative Tradition, edited by R.J. White, published in 1950, and The Road to Serfdom by Friedrich Hayek in 1944. As well as new works, there were reissues in the 1950s of Burke’s Reflections, The Idea of a Christian Society by T.S. Eliot, and C.S. Lewis’ The Problem of Pain. I believe that Blue Jerusalem shows clearly that conservatives were thinking, publishing, and, of course, governing during WWII and also after the cessation of hostilities in Europe.

Kowol identifies three prominent stands within the conservative movement in Britain that, to use Nash’s words, wanted “to change it, restore it, preserve it.” But what were their aims? Let’s start with the “Individualists.” According to Kowol this group was “a loose grouping of organisations and individuals, often connected to trade, shipping, and the City of London, who sought a return to an imagined Victorian political economy.” Their aim or vision was a “Britain free of Government interference and high taxes, where men and women understood the true meaning of work and personal responsibility.” Kowol identifies Ernest Benn, a publisher, as the main protagonist of these Individualists.

The next group, according to Kowol, was the “antithesis of the Society of Individualists’ plan for creating a free trading laissez-faire Britain,” and these were “Conservative Ruralists.” This group was “[p]art of an older and wider tradition of neo-romanticism that blamed modernity for cultural degeneration.” They desired to create a “Britain where the techniques and social relationships of an imagined pre-industrial era had been revived, and the ugliness and enmity of the modern world abolished.” Kowol identifies the historian Arthur Bryant as a fundamental member of the Conservative Ruralists.

The final group of the three identified by Kowol was the “Conservative Industrial Paternalists,” who wanted to harmonize “tradition and technology” and “longed for a revival of leadership in British society” by industry and government working together. Conservative Industrial Paternalists, according to Kowol, “included some of the most famous and influential businessmen of the era,” including Lord McGowan.

Indeed, in the history books and academic papers on the war and its aftermath, the welfare state, such as the NHS, is prominent due to the political left’s dominance in higher education. Nevertheless, Kowol shows that conservatives did think about what to do with the welfare state, but they also had other, and most of the time, more pressing concerns about cultural erosion, institutional stability, and preserving British identity. One of the most interesting parts of the book is about Christianity and military virtues and morals during that era.

Fascinatingly, Kowol writes,

Just as the United Kingdom became more militarised as the war progressed, the State became more Christianised from the summer of 1940 onwards in ways that pleased many Conservatives.

Indeed, there were “National Days of Prayer,” and these days were organized on several occasions during the Second World War, including on May 26, 1940, following the ‘deliverance’ of Dunkirk. Indeed, these were not a one-off occurrence. As Kowol notes, “In total, twelve National Days of Prayer were held during the war, three more than between 1914 and 1918.” Kowol also highlights the role of the BBC, remarking that “The national broadcaster also played an important role in both reflecting the Christian nature of the State and spreading the Gospel during the war” and that “the BBC provided listeners with daily prayers, devotionals, and Christian talks.” Indeed, the BBC commissioned “a variety of accessible and engaging programmes, such as C. S. Lewis’s Mere Christianity and Dorothy Sayers’s The Man Born to be King.”

These two themes of the book, around military virtues and the Christianization of Britain during the war, are fascinating and make the book such an intellectually stimulating read. Reading Blue Jerusalem sparked a memory of when my Nan showed me a video of Churchill visiting Worcester, England (the city of my birth) in 1950 to receive the Freedom of the City. I remember how I remarked about the military virtues of Britain at the time and how Christian Britain still seemed to be back then. Kowol’s book has revived this underappreciated aspect of Britain during and after the war. It seems that today conservatives have a different type of fight on our hands, yet fighting for “Christian civilisation,” as Churchill put it, is still vital. Sayers, in her book Gaudy Night, employs her dilettante sleuth, Lord Peter Wimsey, to express these remarks: “The great advantage about telling the truth is that nobody ever believes it.” I hope this is not the case with Blue Jerusalem, as the truth that Kowol eloquently expresses needs to be believed.

Dr. Daniel Pitt is an Honorary Research Fellow at the University of Buckingham and he was a Summer 2025 Wilbur Fellow at the Russell Kirk Center.

Support the University Bookman

The Bookman is provided free of charge and without ads to all readers. Would you please consider supporting the work of the Bookman with a gift of $5? Contributions of any amount are needed and appreciated!