Something Better Than A Dusty Answer

Something Better Than A Dusty Answer

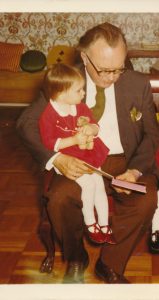

As the Book of Genesis has it, “Dust thou art, and unto dust shalt thou return.” I was forcibly reminded of this hard truth the other day by my second daughter, Cecilia, age 5.

Somewhat imprudently, I had remarked to others, in Cecilia’s presence, that although she is very cute now, she had been unattractive enough at birth. Tiny Cecilia looked at me fixedly, and spoke with controlled passion.

“I want to tell you how ugly you were when you were born,” said Cecilia to me. “You were dust—just dust.”

“Were you there, Cecilia?” I inquired, considerably intimidated.

“Yes, I was there. You were dust.”

***

Cecilia maintains that she always has been in our ancestral house—indeed, that she existed on this spot even before my great-grandfather built our house of Piety Hill. Sometimes I believe her: Cecilia can be preternatural, and ours is a haunted house.

“You put it well, Cecilia,” I replied. “When I am lapped in lead, you can throw the first handful of earth on your father’s coffin, and say ‘Earth to earth, ashes to ashes, dust to dust.’”

“I will,” Cecilia declared. She does love me, nevertheless.

“All are of the dust, and all turn to dust again,” in the words of the author of Ecclesiastes. Were that all, said St. Paul, then he would be the most miserable of men; but out of corruption may rise incorruption. Cecilia, and her sisters Monica and Felicia, know that already.

***

Yet probably most modern folk don’t indulge that hope; according to some public opinion polls, the majority of Americans aren’t even much interested in that possibility. “Eternity! Thou pleasing, dreadful thought!” exclaims Addison’s hero Cato. I think that if a man finds the thought of eternity neither pleasing nor dreadful—why, then that man indeed will return to the dust, having sought nothing better in life than those dusty things called creature comforts.

But though many moderns shrug their shoulders at the prospect of immortality, they do not grow braver. George Bernard Shaw remarks that the average good-natured sensual man is a coward without religion, and will stand by in helpless horror while tyrants usurp the world. Human beings will take deadly risks unselfishly only if they believe that this mortal existence of ours is not the be-all and end-all.

***

Recently my wife talked with a young Scot who was depressed at the possibility of a nuclear war. He demanded a government which would remove war forever from the earth.

“You won’t find that government,” said Annette. “You are slipping into a political religion.”

“But I want to marry and raise a family,” said our young friend.

“Most people do,” Annette told him. “Yet we all die sometime. What if your wife and children should die?”

The young Scot was still more distressed.

“We have to remember this,” Annette went on. “Death doesn’t matter. Haven’t you learned that in your church?”

He hadn’t, though he has been a churchgoer—sometimes two or three times on a Sunday.

The death of the body doesn’t signify, my wife told him. We were made for eternity. How we live, and how we die, do matter. But if we have faith in God—why, “O grave, where is thy victory?”

Our young friend was puzzled, yet Annette had given him something better than a dusty answer. So long as Monica, Cecilia, and Felicia accept that answer, they will live with courage, and do their part in the world.

“Golden lads and girls all must,/ As chimney sweepers, come to dust.”

Just so. But love is more than a rag and a bone and a hank of hair: and out of the ashes rises the phoenix. Remember that, Cecilia, when this too solid flesh of mine is clay again.

Copyright © The Russell Kirk Legacy, LLC

Something Better Than A Dusty Answer

Something Better Than A Dusty Answer