By William F. Meehan III

The earliest inhabitants were the Lenape Indians. The Lenape were a woodland tribe who flourished by farming, hunting, and harvesting seafood. Like most Algonquin tribes, the Lenape harvested the “three sisters”—maize, beans, and squash. Delaware also was occupied at different times by the Dutch, Swedes, and British. Under British rule, in 1682, William Penn acquired Pennsylvania’s three “Lower Counties”—New Castle, Kent, and Sussex—from the Duke of York who had recently acquired New Amsterdam—soon to become New York—from the Dutch, and Penn signed the three counties over to allow formation of Delaware.

New Castle is the northernmost county and the state’s industrial center where among the billowing hills and vales exists a gentle mingling of town and country, while the centrally located Kent is home of the state capital and the least populated county, making life among its wheat fields and peach farms tranquil. Sussex, the southernmost county that comprises nearly half of the state’s land area, is uniquely divided: On the west side is the heart of Delaware’s agriculture industry, which includes mostly corn, soybean, and chicken farming, and on the east are its coastal resorts of Lewes, Rehoboth Beach, Dewey Beach, Bethany Beach, and Fenwick Island. The division, according to United States Department of Agriculture guidelines, also represents an important demarcation in climate: the western half in colder hardiness zone 7a, the eastern half in warmer zone 7b.

It is to the more narrowly identified southeastern part of the county that George B. Hynson in his lyrics, “Our Delaware,” written in 1904 and adopted in 1925 as the state song, refers when he writes in alternating rhyme

Dear old Sussex visions linger,

Of the holly and the pine,

Of Henlopens [sic] Jeweled finger,

Flashing out across the brine.

Writers have not overstated the location’s natural charm. In the early seventeenth century, explorers from Holland, arriving at the Delaware Bay in search for whale oil and other products offered by Indian traders, were amazed by the natural beauty of the landscape and “sweet aroma of the trees” wafting in the sails long before they reached landfall, according to noted First State historian Carol E. Hoffecker. Four hundred years after the Dutch sailors arrived, Rehoboth Beach was celebrating its thirtieth anniversary when a railroad brochure, according to Jay Stevenson in Rehoboth of Yesteryear, promotes the obvious attraction: “The delicious, balsamic odor of the Delaware pine wood pervades her atmosphere.” To publicize his vision for transforming a 180-acre farm along the northern edge of Rehoboth Beach into a seashore residential neighborhood, Wilbur S. Corkran also noted the “luxuriant and fragrant plant life.”

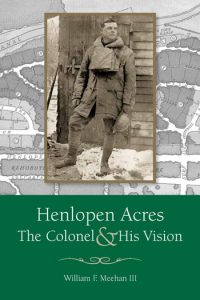

Corkran, the son of a pastor involved in establishing the Methodist Episcopal Church Camps in Rehoboth Beach in the 1880s, spent his childhood summers at the resort town and never lost sight of the resort’s blossoming opportunities. Gifted with imagination and intelligence, Corkran was a rare bird who distinguished himself as an undergraduate at Delaware College (now University of Delaware), as a commanding officer of the 1st Engineer Battalion in France during World War I, and as an engineer assigned overseas for DuPont and later Sinclair-Consolidated Oil Company. It was, however, in designing and building leafy neighborhoods where he expertly blended unique talents as shrewd developer and discerning architect. He first displayed his skill at Brooklawn, an elegant neighborhood in Short Hills, N.J., that served as the blueprint for what was to become, in 1930, the center of his life and work: Henlopen Acres, which was incorporated as a municipality in 1970 and is one of Delaware’s smallest towns.

Buyers, however, were scarce in the Depression years, and Corkran recorded only three sales over the first five years. A driven and disciplined man who approached everything with military precision, Corkran thus had time to apply his knowledge and skill to a program that benefited the greater good: He took charge of the Delaware Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) and spearheaded its mission to rid the state of mosquitos.

President Roosevelt established the CCC with an executive order on April 5, 1933. The CCC was part of his New Deal legislation, combating high unemployment during the Great Depression by putting hundreds of thousands of young men to work on environmental conservation projects. The CCC enrolled mostly young, unskilled, and unemployed men between the ages of 18 and 25.

The men came primarily from families on government assistance and enlisted for a minimum of six months. Each worker received $30 in payment per month for his services in addition to room and board at a work camp. The men were required to send $22 to $25 of their monthly earnings home to support their families.

Corkran’s old U.S. Army unit, the 1st Engineers Battalion, had relocated its headquarters to Fort DuPont in Delaware City in 1922, a year after the government removed guns from the facility and changed its mission from coastal defense. The battalion was now in charge of the CCC Delaware operation, which primarily involved mosquito control. Delaware was the last state to receive federal government funding for its CCC and mosquito control was not a priority in Washington, D.C. The allocation to Delaware, however, not only enhanced living conditions for residents but also led to the arrival of a noted watercolor painter.

The effort to rid Rehoboth Beach of mosquitos started in the early 1920s. Irénée du Pont, who was purchasing property in the Pines neighborhood of Rehoboth Beach, used some of his family’s supply of dynamite to clear nearby Lake Gerar; his purpose was to remove a source for mosquito breeding. In 1928, however, Mary Wilson Thompson, the politically well-connected debutante from Wilmington’s Chateau Country whose father was a major general in the Civil War, made mosquito elimination a state-wide concern.

After summering in Rehoboth Beach for several years, Thompson built a vacation home there, on the north side of the town. Writing in her memoirs, according to the Lewes Historical Society, Thompson thought the home “an ideal resting place” except that “the mosquito question” made conditions “intolerable.”

She persuaded Gov. Clayton D. Buck to form the Delaware State Mosquito Control Commission and mobilized the financial and human resources for cleaning the marshes around Rehoboth Beach and digging ditches along the Lewes-Rehoboth Canal bordering Henlopen Acres. Thompson was thought “crazy” and called the “mosquito woman,” but her campaign proved successful.

Three members of the Delaware College agricultural faculty undertook a study, “Problem of the Mosquito Control in Delaware.” The investigators, who set traps in all three counties, identified the primary pest in Rehoboth Beach: the White-Banded Salt Marsh Mosquito, Aedes Sollicitans, which, they reported, originated in the area’s large acreage of undrained tidal marsh. The study completed in 1933, Thompson lobbied Washington on Delaware’s behalf, requesting the federal government not overlook the First State in its CCC appropriations. And she had just the man to take charge: Wilbur S. Corkran, who happened to be a major in the U. S. Army 1st Engineer Battalion reserves unit now stationed at Fort Delaware. (Corkran would enter WWII a Lt. Colonel and be honorably discharged a Colonel, thus becoming affectionately known as “the Colonel.”)

With Corkran appointed executive officer and engineer, the CCC operation in Delaware was underway. By the end of summer 1935, the Delaware Coast News reported that “the work by CCC boys has practically eliminated the salt marsh mosquito” making southeastern Delaware “almost a paradise to both human and animal life.”

Corkran set up a command post on the second floor of the Lewes Post Office, seven miles from Rehoboth Beach. The executive staff, whose salaries were paid by the State of Delaware, included a secretary and stenographer. Corkran received $450.00 month until 1938 when, with the CCC work slowing down, he requested a reduction of $50.00. Delaware eventually operated eight CCC camps employing more than 5,000 workers, all paid by the federal government.

Corkran’s records at the State of Delaware Archives report on the first two facilities established in November 1933, Lewes (Camp 1224) and Milford (Camp 1226). Each location employed roughly 150 men under the direction of a superintendent, while an engineer reported directly to Corkran for “Special Studies” and other duties.

The goal of the CCC was mosquito elimination in Delaware and involved constructing and cleaning drainage ditches along the state’s numerous canals to remove the source of mosquito breeding. Because the men were between the ages of 18–25 and most of them in their first job, Corkran, at a conference on mosquito control in 1935, explained:

[The] labor is somewhat lacking in efficiency for the first two or three months until the men have had a chance to harden up and gain some degree of experience with the strange and heavy tools on the insecure footing.

Despite these facts, he said, their output was “remarkable” when compared with experienced mosquito control “ditchers.” Over the first thirty months of work, Corkran tabulated with precision, the corps averaged 24.25 feet/hour digging new ditches, while they cleaned existing ditches at a rate of 76.25 feet/hour. That translated, Corkran demonstrated, into more than 1,700 miles for new ditching and over 1,200 miles for ditch cleaning.

Corkran believed the CCC forces under his command should put in an honest day’s work and made his expectations clear in his Operating Manual: Mosquito Control Commission, State of Delaware. According to Corkran’s covering letter to the handbook,

The following instructions, regulations, and charts have been prepared for the work administration of the Civilian Conservation Corps on Mosquito Control in this State, and are hereby published for the purpose of establishing a more definite and efficient routine on the regular work undertaken.

Comprising over one hundred chapters, it provided instruction on topics such as how to predict the weather based on reading the glow of the moon; how to tie knots, splices, and hitches; how to properly dig a ditch; how to cut and clear brush; how to drive a truck through muddy terrain; how to calculate the time one wastes during a work day; and how to handle farmer complaints and build public support.

By spring of 1936, Corkran had sold another lot and was still waiting on development of his seashore neighborhood community. Meanwhile, Louise, his Kentucky-born wife with a knack for horticulture and interior design, was becoming more deeply involved with the local artist community. Together they conceived an idea that would contribute to the state’s enduring cultural heritage: Hire an artist to document the life and work of the Delaware CCC.

Corkran put the word out through the 1st Engineers, who notified the CCC in New York and New Jersey. Fresh out of Rutgers University, art major John I. “Jack” Lewis was the sole applicant for the position and instantly assigned in fall 1936 to Magnolia (#1295), the third CCC facility to open in Delaware. According to his autobiographical record at the Lewes Historical Society,

I signed up for the CCCs, applying for the assignment as Artist in the Camps under Col. W. S. Corkran. I got the job as an Artist Enrollee through my College Art Teacher. It was a special case for a special job. The idea for the position was from the Corkrans. Both the Colonel and his wife were in the Arts. So they decided that the arts should be included in the camps. I was accepted and became a CCC worker with a special assignment from the Director of the Mosquito Control CCC Camps in Delaware to illustrate the work the camps were doing.

My work was to live in the barracks, recording in pencil on sketchpad and in paint on canvas the daily activities of the CCC Men. I would eventually do this work at three of the Delaware CCC camps involved in mosquito control. From 1936 to 1939, I traveled between the three camps located in Lewes, Magnolia, and Leipsic, living in the barracks and going out into the marshes with the work crews to sketch and paint.

In addition to coordinating the efforts of the CCC camps, [Col. W. S. Corkran] would also direct my CCC artistic efforts. His interest in artwork may have founded from his marriage to Louise Chambers Corkran, the founder of the Rehobeth [sic] Art League.

When the CCC operation shut down, Lewis enlisted with the U.S. Army in World War II, joining the Engineer Corps, and lived most of his life in western Sussex County, becoming an art teacher and noted watercolor painter:

Some of this I owed to my time in the CCCs. When I arrived there I was a free style artist. The CCC required me to make realistic reports. It was good training, better than what I received in college.

Lewis’s work hangs in Delaware Legislative Hall in Dover and in private collections and businesses along the Delmarva Peninsula, including murals in the Rehoboth Public Library, Lewes History Museum, and Rusty Rudder in Dewey Beach. One painting of the CCC by Lewis remains in the Permanent Collection of the Rehoboth Art League, the organization Louise formed in 1938 and whose studios are located on the lots where the Corkrans made their home.

This essay is excerpted from Henlopen Acres: The Colonel & His Vision (Connor Creaven, 2020) by William F. Meehan III, a University Bookman contributor.

NEH Support

The University Bookman has been made possible in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities. Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this article do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.