Daniel Buck

Most video games exist for crass entertainment. Others rise above with compelling storylines but remain pop-art at best. A rare few, however, boast the philosophical weight of a nineteenth-century Russian novel. Conservatives overlook this final category to their own detriment.

These designations help outline two categories to facilitate this discussion: There are video games that are akin to sports or board games, and games that are closer to art with narrative, characters, and other markers of fiction.

Regarding the first category, many video games are ultimately a set of rules with an objective, as you would see in a real-world game such as soccer. They may not enhance culture quite like a serious painting but they have value regardless; I would not begrudge any family their time around a table playing Monopoly, just as I would not a group of young adolescents gathered around a television. These games foster leisure and camaraderie.

I would wager that many who think about games think only of this category. But in the almost fifty years since the introduction of the first “classic” popular games such as Pong and Space Invaders, more and more video games have become something more akin to interactive movies. They take you through a compelling plot with dynamic characters, with the difference that in place of observing a protagonist fight or carry on a conversation, you do so. Given this, nothing inherent in the medium can keep a game from achieving artistic greatness like a film or novel.

Of course, any artistic medium has duds. Paperbacks in the grocery checkout line will likely fade into obscurity. How many now-forgotten poets were household names in their time? When considering Elizabethan plays or Victorian novels, we have the advantage of history to sift gold from dross; for video games, we’re still sifting. There is no canon yet, but there well may be if video games can serve the traditional functions of a canon. For example, one purpose of a literary canon is to provide common stories of virtue, heroism, and the clutch of personal characteristics and obligations the Romans called pietas. Whether any one game or set of games can serve that function remain to be seen, but it is not impossible. It is thus imperative that video games of at least the second variety be seen as fields of moral discussion.

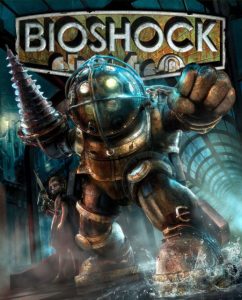

As with the Garden of Eden, though, there’s rot within. Upon arrival, a decrepit human greets you with weapons in hand while a friendly voice crackles onto your radio to explain the situation. The city was utopian; its commitments to market freedom and individualism launched science and commerce to new heights, but the city swiftly showed signs of decay.

As the game progresses, it becomes evident that its creator, Kevin Levine, developed it to be a clear rebuttal to Ayn Rand. References to her novels riddle the game. The city’s founder attempts the destruction of his crumbling utopia rather than see it in the hands of a public bureaucracy, much as the corporatists in Atlas Shrugged destroy their empires. Broken wine bottles bear the name “Fountainhead Cabernet.” In-game posters bear the question “Who is Atlas?” much like the idiom in Atlas Shrugged, “Who is John Galt?” But those are cosmetic allusions. More important thematically, the city’s founder, Andrew Ryan, periodically broadcasts his voice throughout his dystopia. It’s through these words that Levine engages with the ideas he wishes to critique. In one characteristic speech, Ryan’s voice rings over the city’s speakers:

The market does not respond like an infant, shrieking at the first signs of displeasure. The market is patient and you must be too. Rapture is coming back to life even now. Can’t you hear the breath returning to her lungs? The shops reopening, the schools humming with the thoughts of young minds. My city will live. My city will thrive.

Levine could have almost lifted these words directly from Rand’s Atlas Shrugged. They express a blind commitment to the profit motive’s ability to redress imperfection, and that liberty alone fosters human potential.

But Ryan’s invocations echo impotently in a crumbling city, unheard by those in the throes of addiction. The game’s art style only enhances this contrast. It’s intentionally overdone. The colors are saturated and many visuals are quite beautiful but the violence is graphic—your first weapon is a wrench. The victims of drug addiction cackle in the background. It is a game about excess. If publications like The University Bookman seek literature that diagnoses our modern times, BioShock is certainly a contender.

While our society has not succumbed to such dystopian excess, a quick survey of American society challenges any blind commitment to libertarian governance. Too much deference to corporations has allowed chemical companies to hawk opioids as a nonaddictive, miracle drug for pain. Too much deference to the freedom of association and the right to protest has left streets in my own state of Wisconsin aflame for several nights. Too much deference to individual expression has brought glorified child pornography to Netflix amid critical acclaim. Perhaps Rapture and America aren’t so dissimilar.

This topic could warrant a substantial discussion in itself, but the arguments of BioShock mirror current debates within conservatism over the place of classical liberalism, liberty, and the common good. Adrian Vermeule and Sohrab Ahmari are noted critics of liberty as a founding principle, worried that a commitment to it leads a society into excess and libertinism. Unsurprisingly, their argument has much to gain from observing a dystopian work of fiction that satirizes a city committed to free-market fundamentalism and unfettered human nature.

There are countless other games with this same literary weight. Undertale is a seemingly old-fashioned, childish game that quickly develops into a forceful commentary on the practical utility of pacifism and unconditional love. Celeste is a touching allegory of a young woman’s travel into her own mind to face her own anxiety, where the difficulty of the gameplay itself acts as a metaphor for the nature of mental health. Final Fantasy VII is an extended allegory on the nature of original sin. What Remains of Edith Finch tells the heartbreaking tale of a family’s slow capitulation to fate. Spec Ops: The Line is a war game with horrifying images of twenty-first century battle that updates similar themes from Apocalypse Now. Even older games such as Second Life have dealt with important considerations, such as religion and death, both in game in the real world.

Conservatives understand the necessity of rooting ourselves in tradition, but we do ourselves harm if we simultaneously ignore the present. We grumble about the preponderance of pop fiction or the popularity of progressive media but often refuse to engage in popular culture like video games, extolling the good and critiquing the bad, directing the culture to higher ideals. To leave the field to others will open this medium—played, it should not be forgotten, by millions of people, alone and in groups, far more than will access any conservative publication or policy proposal—to the same vulnerability to liberalism as other popular cultural products.

What is needed is a more focused critique by conservatives of what these games do and whether they are conducive to the common good or strengthening positive cultural norms. As Russell Kirk wrote, people will be reading Mad Ghoul comics if they are not taught to read Shakespeare or other literature that elevates the imagination and tells stories of virtue and vice, and how to tell the difference between them. Similarly, the disparity in literary quality between Fortnite and BioShock is akin to the difference between Hunger Games and 1984. People will play Fortnite if they’re not taught to extol the beauty and wisdom within its more thematically rich contemporaries.

Taken as a group, these games are worthy of discussion because they approach high culture. Perhaps they have not yet reached the quality of a Shakespearean sonnet, but the medium is young and some surely will. Plato thought poetry corrupted the soul. Many Victorians believed that novels did likewise. Now poetry and novels are the artistic forms of the erudite and those who aspire to that status. Conservatives who want to shape culture toward the common good should add a new medium to our discussions.

Daniel Buck is a teacher and freelance author who writes about education and literature for sites like The American Mind, Quillette, RealClearPolitics, and City Journal. He has a master’s in education, bachelor’s degrees in English and Spanish, and a certificate to teach English as a second language, all from the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

NEH Support

The University Bookman has been made possible in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities. Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this article do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.