Terrence Malick is American cinema’s one Christian artist and he has now reached his most productive years, his Social Security years. His four recent movies, The Tree of Life (2011), To the Wonder (2012), Knight of Cups(2015), and Song to Song (2017), have introduced a new form of movie to festival audiences and, in one case, to the broader theater audience: the confessional, where characters narrate their experiences and talk in anguish about love and God.

In Malick’s hands, art cinema imitates Augustine’s Confessions with its own accounts of journeying back to faith. In Knight of Cups, the story of a Hollywood screenwriter who goes through debauchery to the contrition of the heart that God requires of the faithful, this is revealed with an important quote from Augustine’s Seventh Homily on 1 John: “Love God, and do what you will.” All four stories are guided by that statement and Malick attempts to prove Augustine right by the eminently rational procedure of reduction to absurdity. He shows characters who try and fail to love God, and thus find it impossible to do what they will.

In this cinema of failure, the potential is more important than the actual. What happens is less important than how it happens. In failure, self-reflection begins. Instead of dialogue, we get narration. Events are overlaid with interpretations, so that regret is mapped on failure, requiring each of us to judge whether the plot then offers a solution, a path to salvation. We are forced to find out for ourselves what we truly believe about being human. Free from the chains of Hollywood happy ends and indie movie unhappy ends, we face the question of what really makes for a happy end to human life—what answers to death.

The little death of unhappiness then becomes prologue to facing mortality in its full terror. Simple stories of love and friendship betrayed, of inconstancy and disloyalty, reveal the full depth of human experience. As the mother says in The Tree of Life, man has two ways between which he must choose: nature and grace, the one capricious and selfish, the other sacrificial and true. The woman says what the movie attempts to prove, that faith is the necessary complement to our self-aware mortality, which threatens to make beasts of us. All four movies reveal such examples of self-debasement, especially in men, only some of whom come to any redemption.

Malick uses the resources of film, image, editing, sound, and actors not to put on a show but to persuade his audience that mood reveals being—that our experience includes intimations of eternity we necessarily then betray in our willfulness. This makes the movies very uncomfortable. The characters themselves and we, their audience, are at one in sensing and resenting the lack of definition and definitiveness in all our actions, even the ones that seem most important. We are not used to having no control over character or action, to facing the unpredictability of being human without being able to look away from it or explain it away.

In these disjointed sequences that add up to long, two-hour movies, we hear the truth of our own inconsistencies. The improvised acting, in abstract settings and lavish modernistic architecture, far from crowds and far from nature, reveal our embarrassment at our own artificial individuality. The bad performance the actors give and the fine performances of the actresses together suggest a contradiction between action and beauty, between doing and seeing, and require that we not hide behind the hope that our actions lead to something good, but instead bring out that very belief in some kind of providence.

This moody cinema reveals our faith that the world is somehow providential. Hence the natural settings, simultaneously breathtaking and opaque. The camera, lingering curiously or cruelly, reveals our own selves projected on images of the world—the hope that beauty announces a merciful God—that we are, if not at home, then at least on our way there. Malick adds classical music, often religious, to complete this experience in an uniquely cinematic way, substituting lyric poetry for storytelling. Instead of arguments or observations he uses cinematic metaphors to project a shadow, the mysterious depth of the characters, and the stakes for which they play.

We have to bring out of our own souls, by resources provided by Malick’s art, the understanding of the humanity of these characters. He works hard to oppose the celebrity-worship that animates popular culture and thematizes that temptation, to prepare us for the characters he invites us to love, the women for their beauty and the men for the anguish the women treat with tenderness. And by loving them we begin to know them. This is the secret teaching of these four movies, that the mood of knowledge is love—that only those beings we love reveal themselves to us, capture our attention fully, and reward it with something good that’s hard to express, but has the certainty of experience.

Thus the women are often shy, girlish in a recognizably American way. They are erotically awake and simultaneously detached from the plot, searching for things that are not as fleeting and distracting as the demons with which the men wrestle. We are invited to see how beautiful these women are and that they are, in their beauty, shameless. Rare though it is at the movies, Malick shows that women are authorities on nobility, guides to men who are perplexed, somehow touched by the divine, such that they retain their essence even if ignored and such that they do not destroy the freedom of the men by enslaving them.

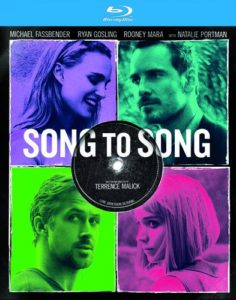

As certain as Malick is that suffering is the only way we learn, he nevertheless insists that what we learn is how to love. That’s the teaching of the priest in Knight of Cups. These four movies are also a secret history of post-war America, going through the generations to build up to an existential crisis, such that the most recent one, Song to Song, features the first female protagonist in a Malick story. She is an aspiring musician in the booming Austin hipster scene, ripe for self-destruction, facing individualism at an existential level, and thus endangering any possibility of salvation, leaving mankind without guides.

She says about herself: “I never knew I had a soul. The very word embarrassed me … Mercy was just a word. I never thought I needed it. Not as much as other people do.” All four protagonists share in this pride. All eventually face the divine requirement from Psalm 51: a contrite heart. They are American types tempted by the injustice they personally suffer to betray their faith and their loved ones. They secretly wish to destroy themselves to take revenge on a world that has deceived them. They are tempted by the ultimate form of individualism, to take control of themselves by suicide when they fail to control the world.

Malick’s solution to this confrontation with mortality is to show that the characters cannot even control that—that they are surprised by love in their hardness of heart and unable to fight it off. Love is a crisis of identity in these stories, a conqueror, and a spiritual war. Knight of Cups emphasizes this by the bookend quotes from Puritan clergyman John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress (1678), a Christian allegory where inscrutable suffering is the only path to God. The movies replay this story with modern experience replacing allegory. Instead of edification, they offer the challenge of self-knowledge, especially Knight of Cups and Song to Song, both stories about young, ambitious artists corrupted by success, who consent to their own debasement, abandon their families, and come close to self-destruction.

Malick’s sympathy for people who debase themselves sexually because they cannot believe they are really real recalls Walker Percy’s joke from Lost in the Cosmos, that man is “the most amazing creature in all the Cosmos: A ghost with an erection!” That’s the paradox of being human. Caught between mind and body, soul itself is endangered in the process, but there is no other path to self-knowledge. They start from freedom as success, willful self-assertion, which leads them to freedom as self-destruction, where nothing one does is real or lasting. That’s nihilism, the confrontation with which makes it possible to think of freedom as the free gift of love.

Thus, in Knight of Cups, we get this myth from Plato’s Phaedrus, about how love pierces the heart, grows wings, and recalls to mind eternity, and thus the destiny of our souls. The same pattern occurs in these four stories, insisting that falling in love is not a choice, but an experience one suffers, a power that humbles individualism. Indeed, Socrates in that dialogue famously talked about forms of love as mania, madness that might have a divine inspiration, and Malick, a student of philosophy, a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford with an unfinished dissertation on Heidegger, is now recreating that experience as cinema.

Titus Techera is a graduate student in political philosophy, and host of the American Cinema Foundation podcasts, and contributor to The Federalist, National Review, and Law & Liberty.