Classic Kirk:

Classic Kirk:

a curated selection of Russell Kirk’s perennial essays

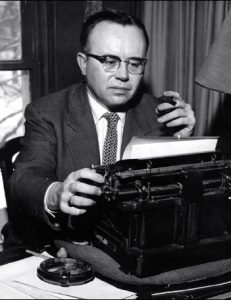

A Note from the Editor

British historian Christopher Dawson (1889 – 1970) is best known for his work that established the significance of religion as the driving force of history and a crucial factor in the rise and fall of civilizations. His books include The Making of Europe, Religion and the Rise of Western Culture, Dynamics of World History, and Progress and Religion.

Dawson influenced a generation of Christian thinkers, including T. S. Eliot and Russell Kirk. In this brief introduction to a biography by Dawson’s daughter, the late Christina Scott, Kirk draws upon Dawson’s historical analysis of religious belief as the means of social renewal.

Christopher Dawson

Introduction by Russell Kirk to A Historian and His World: A Life of Christopher Dawson, by Christina Scott (Transaction Publishers, 1991).

A historian endowed with imagination, Christopher Dawson restored to historical writing both an understanding of religion as the basis of culture and a moving power of expression. This biography by his daughter, Christina Scott, admits the reader to the mind of a remarkable scholar.

“Unfortunately the boredom that is generated in people’s minds by academic history leads to a positive anti-historicism which seems to be becoming characteristic of modern ‘left wing’ thought,” Dawson wrote to G.K. Chesterton in 1932, when Dawson’s book The Making of Europe was published. No critic ever has accused Dawson of being boring; neither has any critic called him unscholarly.

He was a historian so honest and temperate that he was spared most of the slings and arrows commonly directed at English Catholic writers by their Protestant adversaries. His being a convert to Catholicism, nevertheless, had a good deal to do with his not obtaining any full-time university post until, at an advanced age, he was invited to Harvard as the first Stillman Professor of Roman Catholic Studies.

Doubtless it was as well that Dawson was not enrolled in the roster of those “academic historians” who bored him. For Dawson’s writing was done in his own study, among his thousands of books; he was perhaps the last of the great historians so to labor. Dawson’s is the sort of history, marked by intellectual penetration and broad confident learning, that Francesco Guicciardini wrote in his splendid study in the Strozzi-Guicciardini palace. (Dawson’s study, though, is not preserved: Dawson and his wife, Valery, shifted somewhat eccentrically from residence to residence.) Like Guicciardini, Dawson had the mind of a statesman; although unlike Guicciardini, he had no opportunity to practice statecraft. For besides being an eminent historian, Dawson was one of the principal English social thinkers of this century, much influenced by Troeltsch and Le Play; and Dawson’s writings on the twentieth-century “Time of Troubles” in turn powerfully influenced T.S. Eliot.

The liveliest parts of A Historian and His World are the sketches of Dawson’s family, early surroundings, and domestic life. Christina Scott shows us a Victorian and Edwardian England of which the vestiges now are being swept away. Dawson was born in 1889 at Hay Castle (today a huge bookshop) on the Welsh border; he inherited a landed property in Yorkshire, Hartlington Hall, but disliked the duties of a landed proprietor. He accumulated a noble library—part of which he transported to Harvard during his Stillman Professorship, preferring his own books to those of the Harvard stacks. One is reminded of the character Robert Parkinson, “Rotter”, in Wyndham Lewis’s novel Self Condemned. “Parkinson was the last of a species. Here he was in a large room, which was a private, functional library. Such a literary workshop belonged to the ages of individualism. Its three or four thousand volumes were all bookplated Parkinson. It was really a fragment of paradise where one of our species lived embedded in his books, decently fed, moderately taxed, snug and unmolested.”

What was Dawson’s principal achievement? It was to show that all civilizations arise out of religious belief: culture comes from the cult. This understanding, expressed somewhat differently by Arnold Toynbee and somewhat similarly by Eric Voegelin, now begins to dominate the history of ideas, and presently will be reflected in popular histories: Dawson’s studies are winning the day.

* * *

On Easter Day, 1909, young Christopher Dawson sat where Edward Gibbon had sat, on the great steps leading to the church of Santa Maria Aracoeli, in Rome; then and there Dawson determined to write a history of culture; indeed, he vowed it. “However unfit I may be,” he wrote in his journal, “I believe it is God’s will that I should attempt it.”

In the corpus of his writings, Dawson succeeded in fulfilling his vow. Gibbon had cast his contemptuous glance upon the monuments of superstition; Dawson saw in those monuments the power and the truth of Christian culture.

It is altogether possible to look upon such monuments and to despair, as Henry Adams did at Chartres, leaving “the Virgin in her majesty, with her three great prophets on either hand, as calm and confident in their own strength and in God’s providence as they were when Saint Louis was born, but looking down from a deserted heaven into an empty church, on a dead faith.”

But also it is possible, with Christopher Dawson, to hope. As Dawson wrote near the end of his life, “We are living in a world that is far less stable than that of the early Roman Empire. There is no doubt that the world is on the move again as never before and that the pace is faster and more furious than anything that man has known before. But there is nothing in this situation which should cause Christians to despair. On the contrary, it is the kind of situation for which their faith has always prepared them and which provides the opportunity for the fulfillment of their mission.”

The serious study of history virtually has been proscribed in American schools: it is supplanted by “social stew” or else survives for most young people only in the form of an alleged “world history” founded unconsciously upon Voltaire’s Universal History (in which work there occurs a single mention of Christianity, in connection with Constantine’s victory at the Milvian Bridge). Yet a vigorous and imaginative living historian, John Lukacs—influenced by Dawson—argues that history will be the chief literary form of the dawning age, and that a renewed consciousness of the past may redeem mankind from many horrors of the present. If this renewal of the historical consciousness does come to pass, Christopher Dawson may yet be chief among its authors.

Copyright © The Russell Kirk Legacy, LLC

Classic Kirk:

Classic Kirk: