Classic Kirk:

Classic Kirk:

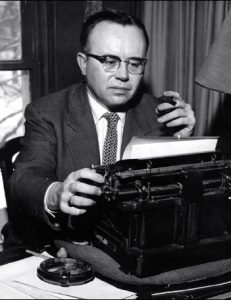

a curated selection of Russell Kirk’s perennial essays

A Note from the Editor

“Throughout my life, I have been comforted by the meditations of the great emperor-philosopher Marcus Aurelius, a conscience speaking to a conscience; it is as if one were conversing with a dear friend,” Russell Kirk wrote in his later years.

In this introduction to the Meditations, Kirk enlivens the noble expression of Stoicism and the high old Roman statesmanship of Marcus Aurelius.

Introduction to Marcus Aurelius, Meditations,

with Epictetus, Enchiridion

Regnery Gateway Editions | 1956

In an age of decadence, the Stoic philosophy held together the civil social order of imperial Rome, and taught thinking men the nature of true freedom, which is not dependent upon swords and laws. In the present little volume, Stoicism is summarized in the writings of two wise men at the extremes of Roman society: Epictetus, servant to servants, and Marcus Aurelius, master of kings. A philosophy imported from Greece blended with the high old Roman virtue, the sense of piety and honesty and office, to achieve in the first and second centuries after Christ a direct influence upon social polity almost unparalleled in the history of moral speculation, and even to inspire a line of philosopher-emperors.

. . . .

The Enchiridion, or Manual, of Epictetus was compiled by the historian Arrian, a devoted pupil of that great teacher, who set down almost verbatim the observations of his master. (Arrian also wrote the Discourses of Epictetus, in eight books, of which four remain to us, and a biography, altogether lost.) Intended to make available within a small compass the remarks of Epictetus most likely to move men’s minds and hearts, the Manual duplicates, in part, the four surviving books of the Discourses.

Two great moralists lived during the reign of the most infamous of tyrants, Nero: Seneca and Epictetus. The former of these Stoics was born to a great estate; but Epictetus came of a humble family in the Hellenized town of Hierapolis, in Phrygia, and from his early years was a slave to Epaphroditus, the freedman and favorite of Nero. Sickly from birth, he is said to have been tortured by his master, and to have learned from hapless suffering that happiness is the product of the will, not of external forces. But his dissolute master, it is thought, sent him to study under the philosopher Musonius Rufus, and thus the obscure slave came to great power over men’s minds unto this day. Epaphroditus, secretary to Nero, was present at that wretch’s sorry death, helping the fallen emperor to slay himself. This act of kindness, possibly the only one Epaphroditus ever performed, was his own undoing: for the fierce Domitian put the former favorite to death on account of it, declaring that no servant ought to presume to violate the divinity which doth hedge an emperor, even at the emperor’s command. Epictetus seems to have been freed after his master’s execution, but he was involved in the general expulsion of philosophers from Rome decreed by Domitian, and so took up his residence in Epirus, where he held his school for many years, dying sometime during the reign of the magnificent Hadrian, whose friend he is believed to have been.

Freedom, Epictetus says, is to be found in obedience to the will of God, and in abjuring desire. Thus Epictetus, the crippled slave, lived and died a man truly free; while Nero, his master’s master, lived and died an abject slave, though seemingly the lord of all the civilized world. For, as Burke remarks, men of intemperate mind never can be free; their passions form their fetters. The Emperor Nero, mastered by his passions, sank to a condition worse than that of any brute; while the obscure Epictetus, disciplining will and appetite, rose to that immortal fame which, to the Stoics, was the only immortality. The liberal mind of the philosopher is reflected enduringly in his manly and pithy prose.

Though it is improbable that Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius ever met while the old teacher was still living, his Discourses were put into the hands of the boy Marcus Annius Verus, destined to bear greater trials than ever the philosopher-slave had known. This book incalculably influenced the mind of the future emperor, making him into a thorough Stoic; and thus, in some sense, the Meditations is a statesman’s sequel to a teacher’s book of maxims.

“Every one of us wears mourning in his heart for Marcus Aurelius,” says Renan, “as if he died but yesterday.” The Meditations, one of the most intimate of all books (its real title is Marcus Aurelius to Himself), seems indeed to be the work of some dear friend of ours, so that the eighteen centuries that lie between the great emperor and us are as nothing. Appreciation of Marcus Aurelius’ thought, however, is a modern thing, for his little book was not generally known until late in the sixteenth century. Ever since then, it has been read more than any other work of ancient philosophy, and has been the especial favorite of military men….

The Meditations seem to have been written during the concluding two years of the Marcomannic War, while the Emperor was engaged in fierce campaigns in the Danubian region, “the spider hunting the fly,” in his words. A successful general, he flung back the Marcomanni and the other German tribes allied with them, and gave Roman civilization two hundred more years of life, in which Christianity might rise to strength so that the collapse of political order would not mean the destruction of everything civilized and spiritual. Similarly, the Stoic philosophy of which Marcus Aurelius was the last great representative prepared the way for the acceptance of Christianity in the dying classical world; and thus, as if he were the instrument of the Providence which he knew to govern this earth, the philosopher-king lived, unknowingly, for the sake of a religion which he persecuted.

He was born Marcus Annius Verus, descended from two distinguished Roman families, in A.D. 121. The magnificent Hadrian admired the boy, who early displayed a character of high generosity and piety; and, near his end, the consolidator of Roman power directed his successor-apparent, Antoninus Pius, to adopt the young man, together with Lucius Verus, and to train them in turn for the mastery of the world. This was done; Marcus Annius became Marcus Aurelius Antoninus, and was associated with his foster-father in the government of the empire, and knew, at the age of seventeen, that one day he might have to bear all the burdens of the civilized world. “Power tends to corrupt,” Lord Acton writes, “and absolute power corrupts absolutely.” Yet it was not so with Marcus Aurelius, though Lucius Verus, for a time his colleague, succumbed to the temptations of his state. Marcus Aurelius was invested with power, or the opportunity for power, as absolute as any man ever has enjoyed outside the Asiatic despotisms; yet he never lost his modesty, even humility, and deferred in everything to the Senate, considering himself the servant of Roman Senate and People. His imperial administration, lasting nineteen years, was marked by prudent and generous reforms at home, conceived in a humane spirit, and by decisive victories on the Parthian and German frontiers; and in all these the Emperor himself was the moving force. Among the leaders of nations, perhaps only Alfred is worthy to be compared with Marcus Aurelius, for beneficent influence: Pericles, St. Louis, and the other philosopher-masters of men are small by his side. History has left only one reproach upon his name, his persecution of the Christians; but this was undertaken out of pure motives, and from a misunderstanding of Christian doctrines, caused by the excesses of the fanatics on the fringe of the then inchoate Christian church.

It was not by intolerance, indeed, but by a charity almost excessive, that his policy was guided. “Pity is a vice,” Zeno, the first Stoic, had declared; but the Stoic Emperor, believing that wickedness was the consequence of ignorance rather than malevolence, was inclined to pardon the greatest ingratitude. He tolerated the licentious Lucius Verus out of pity, and did not sufficiently restrain his brutal son Commodus from similar motives. When Avidius Cassius, an able general, raised the standard of revolt in Asia, Marcus Aurelius offered to abdicate, for the sake of public tranquility; when Cassius’ head was brought to him, he was deeply grieved to have been deprived by assassination of the opportunity to pardon the rebel; and, rather than punish or distress Cassius’ supporters, he burnt all the rebel general’s correspondence, unread, as soon as it was brought to him.

Everyone knows, or ought to know, the splendid description of the age of the Antonines with which Gibbon’s Decline and Fall opens. Of the Antonines, Marcus Aurelius was the wisest and best, and there has been scarcely another period in all history in which justice and order were more secure, and human dignity held in higher esteem. For all that, it was an age morally corrupt, the last effulgence of a dying culture, and the Emperor was infinitely saddened by the vices and follies of the millions of men put into his charge by Providence. He surrounded himself with the most sagacious and upright of the Romans, especially those families whose Stoicism, uniting with the high old Roman virtue, had been proof against the evil Caesars, which line Marcus Aurelius detested. “The advent of the Antonines,” Renan observes, “was simply the accession to power of the society whose righteous wrath has been transmitted to us by Tacitus, the society of good and wise men formed by the union of all those whom the despotism of the first Caesars had revolted.”

This high-principled domination was destined to dissolution only a few years after Marcus Aurelius, worn out at the age of fifty-nine, died near Vienna, in the midst of a campaign, in March, A.D. 180. The reader of Rostovtzeff’s Social and Economic History of the Roman Empire will perceive the causes of this catastrophe; but the moral degradation of the masses which precipitated it, the social ennui that led to the barracks-emperors, is glimpsed with a terrible clarity when one reads of Marcus Aurelius at the gladiatorial shows. Detesting these inhuman displays, even he was compelled, nevertheless, by the force of depraved public opinion, to be present and to receive with disgust the salutes of the poor wretches below in the arena; but, refusing to look at the slaughter, he read books, or gave audiences, during the course of the spectacle; and the ninety thousand human brutes in the crowd, with the jackal-courage of anonymity, dared to jeer him for his aversion. When, in an hour of great public peril, he recruited gladiators in the city to fill the ranks of the decimated legions, the mob threatened to rise against their saviour, crying that he designed to turn them all into philosophers by depriving them of their sport. Stoicism was insufficient to regenerate such a populace: only what Gibbon calls “the triumph of barbarism and Christianity” could accomplish that labor.

Now the Stoic philosophy, of which the Meditations is the last principal work, was peculiarly congenial to the old Roman character, though it was unable to influence deeply the decadent masses of imperial times. It commences in a thoroughgoing materialism: this world is the only world, and everything in it, even the usual attributes of spirits, has a material character; but it is ruled by divine wisdom. God, the beneficent intelligence which directs all things, is everywhere present, and indeed is virtually identical with the universe. The duty of man is to ascertain the way of nature, the manner in which divine Providence intends that men should live. An inner voice informs the wise man of what is good and what is evil. (Most things, including the fleshly enjoyments of life, are neither good nor evil, but simply indifferent.) The Stoic, conforming to nature, looks upon all men, even the vicious and imbecile, as his brothers, and seeks their welfare. He lives, in Marcus Aurelius’ words, “as if upon a mountain,” superior to vanities, and expecting very little of his fellow-men, but helping and sympathizing with them, for all that. We are made for cooperation, like the hands, like the feet. The Stoic does not rail at misfortune, for that would be to criticize impudently God’s handiwork; and he does not seek gratification of ambition, but rather performance of duty; and his end is not happiness, but virtuous tranquility.

As nearly as any man may, Marcus Aurelius approached this ideal of the Stoic philosopher. He lived not for himself, but to do his duty in the exalted station to which Providence had appointed him; and, despite the melancholy which runs through the meditations, he performed his labor with a hopeful spirit. We see him struggling against the weakness of the flesh, as in his playful exhortations (he, being then a sick man, desperately tired) to himself to rise seasonably in the morning, that he might do the work of a man. We see him preferring even the rough and dangerous life of the frontier camp to the sham and treachery of the imperial court. We hear him teaching himself to welcome the approach of death, in addition to other reasons, because if a man were to live longer, he might become such a creature as the depraved poor wretches round him. The sense of the vanity of human wishes is with the Emperor always; but it is borne with a splendid calm:

“To go on being what you have been hitherto, to lead a life still so distracted and polluted, were stupidity and cowardice indeed, worthy of the mangled gladiators who, torn and disfigured, cry out to be remanded till the morrow, to be flung once more to the same fangs and claws. Enter your claim then to these few attributes. And if stand fast in them you can, stand fast—as one translated indeed to Islands of the Blessed. But if you find yourself falling away and beaten in the fight, be a man and get away to some quiet corner, where you can still hold on, or, in the last resort, take leave of life not angrily, but simply, freely, modestly, achieving at least this much in life, brave leaving of it.”

Thus he wrote while he broke the power of the Quadi and Marcomanni beyond the Danube; and his words come down to our age with a meaning still noble enough to hearten us through the Iliad of our woes.

Copyright © The Russell Kirk Legacy, LLC

Classic Kirk:

Classic Kirk: