Classic Kirk:

Classic Kirk:

a curated selection of Russell Kirk’s perennial essays

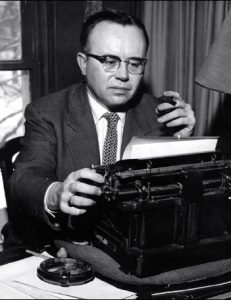

A Note from the Editor

In this brief introduction to a book in honor of Michigan’s 150th birthday, Russell Kirk gives a sparkling tribute to Michigan as a “true commonwealth” with a vivid past. He explains why as a writer he chose to live in a tiny village in the heart of Michigan, noting that “I suppose I am becoming a part of the state’s history.” Indeed, he officially joined that “mysterious incorporation of memories, sentiments, and achievements” when a Michigan Historic Marker was placed outside his home in Mecosta last year.

Michigan Really is a State

Russell Kirk, introduction to Celebrating Michigan: A Chapbook in Honor of Michigan’s 150th Birthday, edited by David Vinopal (Big Rapids, Mich.: Ferris State College, 1987).

Most of the fifty states of the Union seem artificial creations, their boundaries mere arbitrary parallels of latitude and longitude, their annals short and simple, their culture indistinguishable from the general mass-culture of North America. But it is otherwise with Michigan, a true commonwealth, a body politic with natural frontiers, a history running back to the middle of the seventeenth century, and a character of its own.

Sometimes I have been asked why I live in a decayed village at the heart of Michigan, when (the inquirer suggests) I might live anywhere in the world that should please me. I answer that my home is Mecosta, Michigan; what strength I possess comes from old roots here; and some of us, in this age of purposeless mobility, ought to abide where they were born or reared, for the sake of the permanent things.

“Happy the land that has no annals,” we are told. Yet I should be discontented in a state without a vivid past. In Michigan the memorials of vanished generations remind us that we Michiganians participate in a continuity joining the living, the dead, and those yet to be born: a community of souls, we Michigan folk.

Nothing in these United States more strongly evokes bygone times than Mackinac Island, the last sanctuary from Demon Auto. There is no other American cluster of venerable buildings, amidst green lawns, so amusing and charming as Greenfield Village. At eighteen, I was a Greenfield Village guide; at sixty-eight, a proposer of toasts at the Grand Hotel, Mackinac.

Aye, this is a haunted state, with its ghostly bold voyageurs, heroic Jesuits, raiding Indians, British garrisons, schismatic Mormons, ships’ captains, lumber barons: a state to wake young folks’ imagination. My ancestors are a part of its history, coming first from the Burnt-Over country of upper New York to the hopeful little settlements of Mendon and Leonidas—now shadows of themselves—and later shifting northward to the forests. Perhaps my wife has a better claim still to ancient roots here: Annette, nee Annette Yvonne Cecile Courtemanche, of French and Indian stock. Was it not the Sieur de Courtemanch who built Fort Saint Joseph, near where Niles now stands, and protected the Miamis?

In Michigan I was born, next door to the railway station at Plymouth, with the steam locomotives (my father the engineer aboard one) hooting us into silence every quarter of an hour; in Michigan I expect to be buried, at Mecosta, where there are still woods and fields and many lakes. In my time I have talked with Henry Ford and other of the automobile pioneers; delivered an oration at Pere Marquette’s monument; lectured or taught at nearly all the colleges and universities in the state; written my twenty-five books, to date; restored old houses and built a new one in archaic style; have even risen to the dignity of a justice of the peace, while we still had justices. In this year of Michigan’s Sesquicentenary, I suppose I am becoming a part of the state’s history, a subject for an elegy in a Mecosta churchyard.

The lovely Annette declares that Michigan’s chief endowment is the state’s water, and right she is. The inland seas are our richest resource and guardians of our peculiar Michigan identity. The numberless lakes, once regarded by farmers as so many misfortunes, give beauty to the state, and popularity too. As for the streams, I canoe the Chippewa and the Little Muskegon, and explore channels and swamps, with as much pleasure as if I never had paddled before. How good not to dwell in Kansas!

The worst form of alienation for an American writer, my old friend T. S. Eliot said, is residence in New York City. I have lived in the Hebrides and in the Italian palazzi, but never have been tempted to desert Michigan for long—certainly not for Madison Avenue or Greenwich Village. The very barrenness of the stump country charms me. And so it is, I fancy, with many of the writers and artists who contribute to this present little volume.

Few, if any, of us will be contributing to a chapbook for Michigan’s Bicentenary. Yet half a century from now, when some pious spirits (pious in the old Roman sense) are turning over the pages of the 1987 chapbook and chuckling at its quaint turns of language, Michigan still will retain its old character and flavor, we may hope. And we, quite conceivably, by Anno Domini 2037 may have ourselves become a part of that mysterious incorporation of memories, sentiments, and achievements which is called the genius of Michigan.

Copyright © The Russell Kirk Legacy, LLC

Classic Kirk:

Classic Kirk: