Classic Kirk:

Classic Kirk:

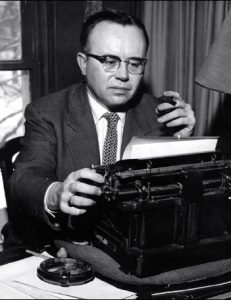

a curated selection of Russell Kirk’s perennial essays

A Note from the Editors

In “The American Mission,” Russell Kirk counsels us to take a fresh look at that “champion of ordered freedom,” Orestes Brownson. Brownson argued a timely point: that the central problem of politics is the reconciling of authority and liberty. He discerned that it was this country’s mission “to present to mankind a political model: a commonwealth in which order and freedom exist in a healthy balance or tension.” Although this view of America is contested today, Kirk was steadfast that America remains the best hope for a just order.

Originally delivered as a public lecture at the Heritage Foundation, this piece was later included in a collection of Kirk’s lectures titled Redeeming the Time.

The American Mission

From Redeeming the Time (ISI Books, 1996)

Does the nation called the United States of America possess a mission, providentially ordained? If so, does America have the ability and the courage to pursue that mission, at the close of the twentieth century?

Four decades ago, during the Eisenhower era, we heard much talk about the “American Century”; and there was printed much discussion—some of it superficial, and the rest not conspicuously imaginative—about American national goals. Since then, American expectations often have been chastened. If it remains possible that this still may become the American Century in the eyes of future historians, what is America’s mission?

Let us repair, with this question in mind, to Orestes Brownson, who was born in 1805 and died in 1876. Lord Acton, possessed of one of the better intellects of the nineteenth century, believed that Orestes Brownson was the most penetrating thinker of his day. That was a high compliment indeed, for in the United States it was the day of Hawthorne, Melville, Emerson, and a half-dozen other men of the first rank—not to mention the great Victorians of Britain. Brownson was a considerable political philosopher, a seminal essayist on religion, a literary critic of discernment, a serious journalist with fighting vigor, and one of the shrewder observers of American character and institutions.

Although a radical in his youth, Brownson became after 1840 a formidable defender of the permanent things. He was the first writer to refute Marx’s Communist Manifesto.

“In most cases,” Brownson wrote in 1848, replying to Marx, “the sufferings of a people spring from moral causes beyond the reach of civil government, and they rarely are the best patriots who paint them in the most vivid colors, and rouse up popular indignation against the civil authorities. Much more effectual service could be rendered in a more quiet and peaceful way, by each one seeking, in his own immediate sphere, to remove the moral causes of the evils endured.”

Without Authority vested somewhere, Brownson told the Americans of his age, without regular moral principles that may be consulted confidently, justice cannot long endure anywhere. Yet modern liberalism and democracy, he continued, are contemptuous of the whole concept of moral authority. If not checked in their assaults upon habitual reverence and prescriptive morality, the liberals will destroy justice not only for their enemies, but for themselves. Under God, Brownson emphasized, the will of the people ought to prevail; but many liberals and democrats ignore that prefatory clause.

Brownson was an outspoken champion of the American Republic. His book entitled The American Republic was published the year after the end of the Civil War; it contains his most systematic exposition of the idea of the American Mission.

Every living nation, Brownson wrote in that book, “has an idea given it by Providence to realize, and whose realization is its special work, mission, or destiny.” The Jews were chosen to preserve traditions, and that the Messiah might arise. The Greeks were chosen for the realizing of art, science, and philosophy. The Romans were chosen for the developing of the state, law, and jurisprudence. And the Americans, too, have been appointed to a providential mission, Brownson declared. America is meant to continue the works of the Greeks and the Romans, but to accomplish yet more. The American Republic has the mission of reconciling liberty with law.

Brownson was a champion of ordered freedom. Yet America’s mission, he added in 1866, “is not so much the realization of liberty as the realization of the true idea of the state, which secures at once the authority of the public and the freedom of the individual—the sovereignty of the people without social despotism, and individual freedom without anarchy. In other words, its mission is to bring out in its life the dialectical union of authority and liberty, of the natural rights of man and those of society. The Greek and Roman republics asserted the state to the detriment of individual freedom; modern republics either do the same, or assert individual freedom to the detriment of the state. The American republic has been instituted by Providence to realize the freedom of each with advantage to the other.”

So America’s mission, as Brownson discerned it, was to present to mankind a political model: a commonwealth in which order and freedom exist in a healthy balance or tension—in which the citizen is at once secure and free. This reconciling of authority and liberty is the central problem of politics. As the German scholar Hans Barth points out, Edmund Burke is the most important political thinker of modern times precisely because Burke understood the necessary tension between the claims of order and the claims of freedom. In America, Orestes Brownson discerned this cardinal problem of politics better than did anyone else.

The American Republic has the mission of reconciling liberty with law.

The reconciling of authority and liberty, so that justice might be realized in the good state: that mission for America is not yet accomplished, a century and a quarter after Brownson wrote; but neither is that mission altogether forgotten. Under God, said Brownson in his emphatic way, the American Republic may grow in virtue and justice. A century later, the word “under God” would be added to the American pledge of allegiance.

Yet also, during the past three decades, the influence has grown of those Americans who would prefer to stride along without any divinely-ordained mission—who believe, indeed, that the American Republic could do famously without bothering about God. The Supreme Court of the United States has tended to side with these militant secularists, correctly styled “humanitarians” by Brownson. Humanitarian liberals, Brownson wrote in his American Republic, are the enemies—if sometimes the unwitting enemies—of true freedom and true order.

“The humanitarian democracy,” Brownson said, “which scorns all geographical lines, effaces all individualities, and professes to plant itself on humanity alone, has acquired by the [Civil] war new strength, and is not without menace to our future.” Brownson declares that the humanitarian presently will attack distinctions between the sexes; he will assail private property, as unequally distributed. “Nor can our humanitarian stop there. Individuals are, and as long as there are individuals will be, unequal: some are handsomer and some are uglier, some wiser or sillier, more or less gifted, stronger or weaker, taller or shorter, stouter or thinner than others, and therefore some have natural advantages which others have not. There is inequality, therefore injustice, which can be remedied only by the abolition of all individualities, and the reduction of all individuals to the race, or humanity, man in general. He [the humanitarian] can find no limit to his agitation this side of vague generality, which is no reality, but a pure nullity, for he respects no territorial or individual circumscriptions, and must regard creation itself as a blunder.”

This humanitarian, or social democrat (here Brownson uses these terms almost interchangeably), is by definition a person who denies that any divine order exists. Having rejected the supernatural order and the possibility of a Justice that is more than human, the humanitarian tends to erect Envy into a pseudo-moral principle. It leads him, this principle of Envy, straight toward a dreary table land of featureless social equality—toward Tocqueville’s “democratic despotism,” from which not only God seems to have disappeared, but even old fangled individual human beings are lacking.

A truly just society is not a democracy of degradation, Brownson argues. The just society does not reduce human beings to the condition of identical units on the dismal plain of absolute equality. The just society will not speak in the accents of envy, but will talk of order, duty, and honor.

In any particular country, Brownson maintains, the form of government must be suited to the traditions and the organic experience of the people. In some lands, therefore, the form of government will be monarchy; in others, aristocracy; in America, republicanism or democracy under God. America must not contest the sovereignty of God, which is absolute over all of us. The American government must secure to every citizen his freedom. And from such freedom comes the justice of which Plato wrote in his Republic, and Cicero in his Offices: the right of every person to do his own work, free of the meddling of others.

Such is the character of true social justice, Brownson tells us: a liberation of every person, under God, to do the best that is in him. Poverty is no evil, in itself; obscurity is no evil; labor is no evil; even physical pain may be no evil, as it was none to the martyrs. This world is a place of trial and struggle, so that we may find our higher nature in our response to challenges.

It is America’s mission, Brownson told his age, to offer to the world the example of such a state and such a society, at once orderly and free. A year after Brownson published The American Republic, Marx published Das Kapital. Among the more interesting concepts in that latter work I find this confession by Marx: “In order to establish equality, we must first establish inequality.” Marx means that to make all men equal, we must first break the strong, the energetic, the imaginative, the learned, the thrifty; they must be broken, indeed, by the dictatorship of the proletariat. Then, having established by force a universal mediocrity, we may enjoy the delights of total equality of condition.

The American mission, Brownson knew so early as 1848, is to show all nations an alternative to the dreary socialist sea-level egalitarian society of equal misery. To that high duty, Brownson earnestly believed, the American nation has been appointed by divine providence.

Do Brownson’s phrases ring strange in our ears? Yes, they do, in some degree. And why? Because the humanitarians—that is, the folk who take it for granted that human nature and society may be perfected through means purely human—have come to dominate our universities, our schools, our serious press, most of our newspapers, our television and our radio. The thought, and the very vocabulary, of this Republic have fallen under the domination of humanitarian ideology. Why, the churches themselves, or many of them, have been converted into redoubts of humanitarianism, issuing humanitarian fulminations or comminations against such public men as still stubbornly maintain that politics is the art of the possible.

Some popular revolt against humanitarian dogmas is obvious enough today. As George Santayana put it, it will not be easy to hammer a coddling socialism into America. It is still less easy to eradicate altogether the influence of religious belief in the United States—hard though the humanitarian zealots have been laboring at that task. Yet whether traditional Americans retain coherence and intellectual vigor sufficient to undo humanitarian notions and policies—why, that hangs in the balance nowadays. The tone and temper of American thought and public policy have drifted, for the last three decades at least, toward the humanitarian goal of a materialistic egalitarianism, toward what Robert Graves calls the ideology of Logicalism: that is, a social Dead Sea without imagination, diversity—or hope. It is not that the humanitarians have been especially numerous: rather, their work has been accomplished by small circles of intellectuals, centered chiefly in New York City. Yet ideas do have consequences. America’s media of opinion increasingly have reflected the assumptions of that humanitarianism which Brownson denounced in his day.

Some of the unpleasant consequences of humanitarian intellectuality having become apparent to a large part of the American public, that public has begun to react at the polling-booths. (A human body that cannot react, I venture to remind you, is a corpse.) Also there has occurred some healthy reaction intellectually against humanitarian ideology. Yet this reaction comes late, and is relatively feeble as yet: consider, for instance, the continued domination of book-publishing by humanitarian liberals; or the prejudices of most professors; or the fewness in numbers of those theologians and church leaders of intellectual powers who boldly assert that Christianity and Judaism are transcendent religions, not instruments for the destruction of society’s cake of custom.

How does this contest between the American humanitarians and the American traditionalists affect the question of the American mission? Why, part of this struggle is a competition between two very different concepts of what the American mission ought to be. I have outlined already the traditionalists’ understanding of the American mission: that is, to maintain and improve a Republic in which the claims of freedom and the claims of order are balanced and reconciled—a Republic of liberty under law, endowed with diversity and opportunity, an example to the world. There exists also a humanitarian, or social-democratic, understanding of the American mission, which already has brought upon us disastrous consequences, in domestic policy and in foreign policy. Permit me to suggest the character of this humanitarian notion of America’s mission, with a few illustrations of its practical effect.

The words “humane” and “humanitarian” mean quite different things. The humanitarian believes in brotherhood: that is, “Be my brother,” he says, “or I’ll kill you.” He aspires to assimilate others to his mode and substance.

The humanitarian, whose roots are in the French Enlightenment (full of enlighteners, but singularly lacking in light, Coleridge says), suffers from the itch for perpetual change. Change in what direction? Why, change away from superstition (by which he means religion), from old customs, from established constitutions, from anything that is private (property especially), from local and national affections, from the little platoon that we belong to in society. And change toward an arid rationalism, toward emancipation from old moral obligations and limits, toward a classless “people’s democracy,” toward collectivism and total equality of condition, toward a sentimental internationalism (a world without diversity), toward concentration of power. The aim of humanitarianism—that is, the ideology which denies the divine and declares the omnipotence of human planners—is singularly inhumane. Were it possible for the humanitarians to accomplish their design altogether, humankind would be reduced to the inane and impoverished state foretold by Jacquetta Hawkes in her fable “The Unites.”

To understand the humanitarian mentality, American variety, to which I refer, we may turn to Santayana’s novel The Last Puritan. In that shrewd and moving book, we encounter a minor character, Cyrus P. Whittle, a Yankee schoolmaster, a “sarcastic wizened little man who taught American history and literature in a high quavering voice, with a bitter incisive emphasis on one or two words in every sentence as if he were driving a long hard nail into the coffin of some detested fallacy…. His joy, so far as he dared, was to vilify all distinguished men. Franklin had written indecent verses; Washington—who had enormous hands and feet—had married Dame Martha for her money; Emerson served up Goethe’s philosophy in ice-water. Not that Mr. Cyrus P. Whittle was without enthusiasm and a secret religious zeal. Not only was America the biggest thing on earth, but it was soon going to wipe out everything else: and in the delirious dazzling joy of that consummation, he forgot to ask what would happen afterwards. He gloried in the momentum of sheer process, in the mounting wave of events; but minds and their purposes were only the foam of the breaking crest; and he took an ironical pleasure in showing how all that happened, and was credited to the efforts of great and good men, really happened against their will and expectation.”

Here we have the American humanitarian in a nutshell. For the humanitarian, America’s mission is “to wipe out everything else”—to destroy the old order in all the rest of the world, the old faiths, the old governments, the old economies, the old buildings, the old loves and loyalties. And in the delirious dazzling joy of that consummation, the American humanitarian forgets to ask what would happen afterwards.

The influence of this evangelical humanitarianism, this very odd passion for doing good to other people by virtually or literally effacing them, is not confined to one American party or one American class. One thinks of President Wilson, sure that he could make the world safe for democracy by resort to arms—and succeeding, as he saw himself toward the end, merely in delivering eastern Europe into the hands of the Bolsheviki. One thinks, too, of the designs for Americanizing Africa that Colonel House put into Wilson’s head—but which never came to pass.

Or one thinks of President Franklin Roosevelt’s privately-expressed detestation of the French and British systems, and of his intention (frustrated by events) to make all of Africa (after an expected victory at Dakar) into an American sphere of influence. One thinks, too, of the courses of Presidents Kennedy and Johnson in Indo-China, and of their illusion that American-style democracy, middle-of-the-road parties and all, could be established instantly in Vietnam and neighboring states—if only persons like President Diem were swept away, by such means as might be thought necessary.

I have heard this humanitarian doctrine about America’s mission expressed from a Washington platform (which I shared) some four decades ago by the president of the Chamber of Commerce of the United States. If only all the peoples of the world, he said in substance, could be induced or compelled to abolish their old ways of life and become good Americans, emancipated from their ancient creeds and habits, buying American products—why, how happy they all would become!

And these humanitarian doctrines were preached forty years ago by an eminent official of the American labor movement—who confessed indeed that this humanitarian Americanizing might take a century or more of turmoil, and must include the destruction of all existing ruling classes, the driving of handicraft producers to the wall, and the overwhelming of all old religions. But (borrowing a phrase from Robespierre) you can’t make an omelet without breaking eggs, you know, he reminded his readers. And think of how happy everybody everywhere will be when everything but an amorphous Americanism is wiped out!

Such is America’s mission as perceived by the humanitarian. Yet there remains that very different kind of American mission for which Brownson hoped. Probably Brownson’s concept of a national mission was derived in part from Vergil’s idea of fatum—that is, fate, destiny, mission.

In the age of Augustus, the poet Vergil aspired to consecrate anew the mission of Rome. He did not prevail altogether against the pride, the passion, and the concupiscence of his time: no poet can do that. Yet had there been no Vergil, rousing the consciences of some men of the Empire, the imperial system would have been far grosser and more ruthless than it was. Had it not been for Vergil, the society of the early Empire might have been consumed by its own materialism and egoism. Vergil perceived at work in Roman civilization a divine mission—a purpose for which the Christian adjective is “providential.” Communicating that insight to the better minds of his age and of succeeding generations, Vergil made of Romanitas, the Roman culture, an ideal which in part fulfilled his prophecy of Rome’s mission.

By fatum, Vergil meant the Roman imperial destiny—Rome’ s duty, imposed by unknowable powers, to bring peace to the world, to maintain the cause of order and justice and freedom, to withstand barbarism. For Vergil, this mission was the true significance of Rome’s history.

So it was with Brownson’s idea of the American mission. The achieving of that mission seemed remote about the time when Brownson described his principle of “the dialectical union of authority and liberty.” We have not yet achieved that mission. But today, America has arrived, probably, at its maximum territorial extent, its maximum population (or nearly that), and its height of political, military, and economic power. We Americans, like the Romans of the age of Augustus, must make irrevocable choices. At that time, Rome had either to renew the idea and the reality offiatum, or else to sink prematurely into private and public corruption, internal violence, and disaster on the frontiers. Just so is it with us now.

Then what is America’s mission in our age? It remains, as Brownson put it, to reconcile liberty with law. The great grim tendency of our world is otherwise: sometimes toward anarchy, but more commonly toward the total state, whose alleged benefits delude. This is no easy mission, even at home: consider how many people who demand an enlargement of civil liberties at the same time vote for vast increase of the functions and powers of the general government.

So America’s mission, as Brownson discerned it, was to present to mankind a political model: a commonwealth in which order and freedom exist in a healthy balance or tension—in which the citizen is at once secure and free. This reconciling of authority and liberty is the central problem of politics.

And this mission is more difficult still in the example the United States sets for the world. If we are to experience a Pax Americana, it will not be the sort of American hegemony that was attempted by Presidents Truman and Eisenhower and Kennedy and Johnson: not a patronizing endeavor, through gifts of money and of arms, to cajole or intimidate all the nations of the earth into submitting themselves to a vast overwhelming Americanization, wiping out other cultures and political patterns.

An enduring Pax Americana would be produced not by bribing and boasting, but by quiet strength—and especially by setting an example of ordered freedom that might be emulated. Tacitus said that the Romans created a wilderness, and called it peace. We may aspire to bring peace by encouraging other nations to cultivate their own gardens: in that respect, to better the Augustan example.

So much for the precepts of Vergil and Brownson. Either, in the dawning years, we Americans will know Augustan ways—or else we may find ourselves in a different Roman era resurrected. It might be the era of the merciless old Emperor Septimius Severus. As Septimius lay dying at York, after his last campaign, there came to his bedside his two brutal sons, Geta and Caracalla, asking their father how they should rule the Empire once he had gone. “Pay the soldiers,” Septimius told them, in his laconic fashion. “The rest do not matter.”

In such servitude, lacking both order and freedom, end nations whose mission has been false, or who have known no mission at all. To borrow phrases again from The Last Puritan, Americans always were consecrated to great expectations. Adherents to the old traditions of America know that we are not addressed to vanity, to some gorgeous universal domination of our name or manners. Nor are we intended to play the role of the humanitarians with the guillotine. The American mission, I maintain with Brownson, is to reconcile the claims of order and the claims of freedom: to maintain in an age of ferocious ideologies and fantastic schemes a model of justice.

© The Russell Kirk Legacy, LLC

Classic Kirk:

Classic Kirk: